Stigma, Lack of Awareness Holding Back Use of HIV Prevention Pills, Experts Say

By Thabo Molelekwa for Spotlight

Over the last four years South Africa has taken large strides in making HIV prevention pills available at public sector clinics, but uptake has not been as good as some may have hoped. Thabo Molelekwa asks several experts why this might be.

HIV prevention pills, also referred to as oral pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP), contain a combination of two antiretroviral medicines. They are highly effective at preventing HIV infection when taken as prescribed by someone not living with HIV.

But while the pills are now available through most public sector clinics in the country, not as many people are using them as one might have expected. According to the most recent estimates from Thembisa, the leading mathematical model of HIV in South Africa, only around 4% of sexually active adolescent girls and young women used PrEP in 2022. This is a substantial improvement on 0.6% in 2020, but given that the rate of new HIV infections in adolescent girls and young women has remained stubbornly high, one may have expected this number to be higher by now.

“So the rates of uptake are definitely increasing in South Africa, but not to the point that we would hope. There’s still definitely a gap between people who would benefit from being on PrEP or alternative HIV prevention methods and those who are actually accessing the biomedical daily oral prevention,” says Cheryl Hendrickson, a Senior Researcher at the Health Economics and Epidemiology Research Office (HE²RO) at the University of the Witwatersrand.

Ongoing stigma

One explanation for uptake not being better is the ongoing impact of HIV-related stigma. A recent study conducted among young people in Gauteng found that stigma and a lack of confidentiality continue to impede PrEP adoption. The researchers identified several barriers for PrEP-naive participants, including limited knowledge, negative staff attitudes, and misconceptions about side effects. Structural factors like healthcare provider bias and a lack of culturally sensitive interventions were also found to hinder PrEP uptake. The research was conducted by HE²RO – Hendrickson was a co-author.

“Participants were worrying about their families or friends thinking they were taking ARVs,” says Constance Mongwenyana-Makhutle, a research associate and co-author of the study.

Professor Linda-Gail Bekker, CEO of the Desmond Tutu HIV Centre, also emphasises the persistent role of stigma. “People don’t want to be associated with HIV, HIV risk or any misconception that they may be living with HIV and on antiretroviral therapy,” she tells Spotlight.

The perception around PrEP, says Dr Fareed Abdullah, Director of AIDS and TB Research at the South African Medical Research Council, is similar to that of contraception. “Basically, a young person would consider it an admission that they are sexually active and consider themselves to be at risk of HIV; thereby inviting judgement and stigma from others, especially healthcare workers,” he says.

Not enough awareness?

Closely related to the issue of stigma is awareness. Here COVID-19 may have played a role. As the provision of PrEP through public sector clinics gained momentum in 2020, many potential PrEP users would have stayed away from clinics due to pandemic-related restrictions and fear of contracting SARS-CoV-2. The pandemic also meant that any plans to build awareness of PrEP would have had a hard time finding purchase, at least in 2020 and 2021.

Reflecting on past HIV awareness campaigns, Bekker stresses the need for increased public demand creation for PrEP

“I think we have not had enough public demand creation- if you think of the campaigns for getting people to take up COVID vaccines….then we really haven’t done enough in this regard. It is a new concept- a pill a day to prevent HIV ……and so people need to have the idea socialised and normalised so that there is also a reduction in stigma,” she says.

What happens at the clinic

Another barrier to PrEP uptake is likely that while PrEP is being made available through public sector clinics, not everyone feels welcome at, or like to visit, their local clinic.

Bekker says youth complain that government clinics are often a barrier for them to access PrEP. “Their hours, their long queues, their discrimination and sometimes the prejudicial attitudes drive young people away,” she says.

Bekker argues that some of these barriers would be removed if HIV prevention measures was taken outside of health facilities and into community spaces.

“PrEP for young people in the public sector is free. If they want to use private pharmacies though, they would need to pay currently. I think more can be done to make PrEP and other sexual and reproductive health services more readily available so that young people, in a way, have no excuses not to make sure they are using them … colleges, universities and even secondary schools could also reach more young people. If we want to reduce STIs and unintended pregnancies in our adolescents, we are going to have to be sure there are very few barriers to these contraceptive and prophylactic services,” says Bekker.

Hendrickson points out that there are several projects around the country that are looking at alternative service delivery methods. “There’s a project that’s looking at prep delivery in pharmacies. Currently, they are providing oral prep, and hopefully soon, they will provide injectable prep within several pharmacies in Gauteng and the Western Cape,” she says. According to her, the pharmacy model appeals especially to men.

Healthcare worker attitudes and training

Related to the issue of visiting public healthcare facilities to access PrEP, healthcare worker attitudes and training has also been flagged as a concern.

Bekker says some health care professionals are not trained to deal with young people in their diversity. “Adolescents are a very distinct population – they can be offended, they value their privacy, and they can make health choices and decisions but need supportive, empathic and tailored information that they can use,” she says.

Abdullah makes a similar point. If some health care workers are properly trained, can identify people at high-risk and understand the efficacy of the intervention, then the vast majority would follow and offer the service in a professional manner, he says.

Ritshidze, a community-based healthcare monitoring group, say they have observed an increase in the number of healthcare facilities where staff say they prioritise offering PrEP to members of key populations such as young women and adolescent girls or men who have sex with men. Of 394 clinic staff surveyed earlier this year, 97% said they prioritise young women and adolescent girls.

But when Ritshidze asked users of healthcare facilities whether they’ve been offered PrEP, the numbers were much lower. “Compared to data collected in 2022, our 2023 data report a lower percentage of people saying they have been offered PrEP for most population groups,” Ritshidze say in a recent report. Complaints about negative staff attitudes have been a running theme in Ritshidze’s reports on public sector healthcare facilities over the last three years.

Actual and perceived risk

Abdullah suggests another barrier to PrEP uptake. There is a perception that HIV is no longer an urgent priority and that the risk of infection is low. This, he says, has led to lower public awareness of the importance of behaviour change and the need for young people at risk to protect themselves.

Recent data from a Human Sciences Research Council survey and the District Health Barometer indicate that condom use is declining in South Africa. While the reasons for the decline are not clear, one theory is that it is driven by the perceived risk of HIV infection having reduced over time.

Will more choice help?

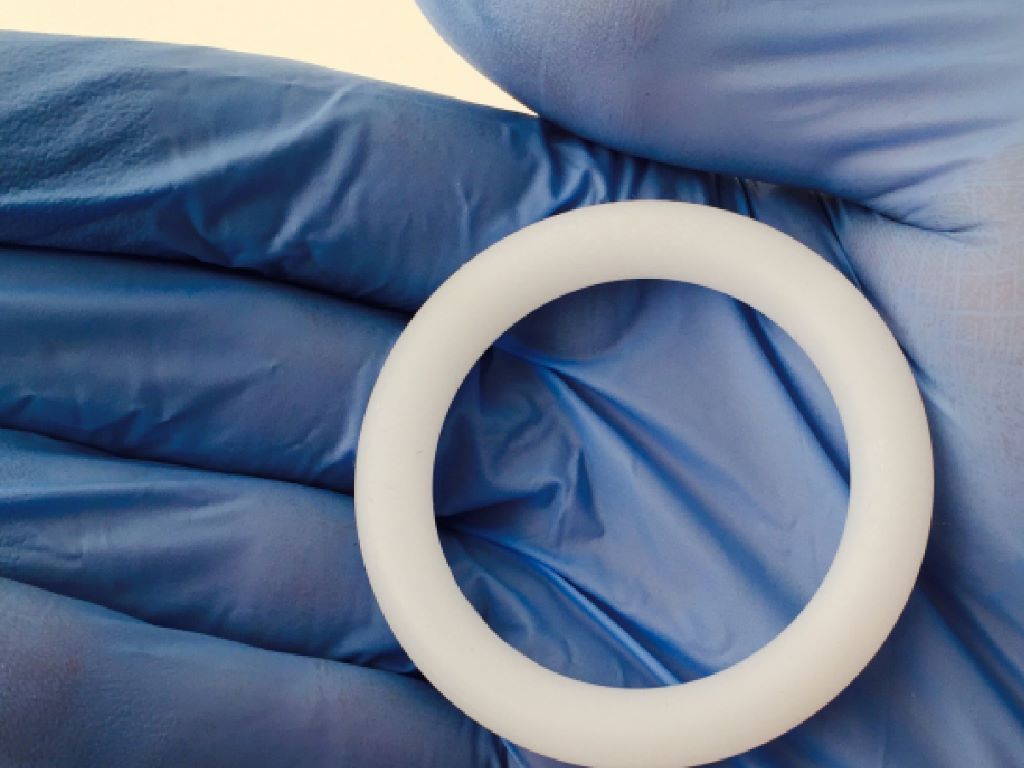

Currently only oral PrEP is routinely available in the public sector, but PrEP in the form of a two-monthly injection and a monthly vaginal ring have been approved by the South African Health Products Regulatory Authority and is being offered to people taking part in pilot projects. It is likely that the prevention injection will become much more widely available once its price drops sufficiently – which is anticipated to happen once generic manufacturers enter the market in around three years’ time. Products that combine PrEP and a contraceptive into a single pill or injection are also under development.

Mitchell Warren, director of Avac, a global HIV advocacy organisation, is optimistic about people being offered a choice between the three types of PrEP. While condoms were widely available in public clinics in the 1990s, Warren says he noted the desire of people to buy condoms from spaza shops, shebeens, or pharmacies. This didn’t replace clinic supplies, he clarifies, but it did bring into sharper focus the importance of providing choice to people.

“But even with three different PrEP options, what we clearly have known for many years now is that PrEP is not only about the products, PrEP is really a programme, helping people identify not just their personal risk, but their desires, what they want and need out of relationships,” he says.

Government perspective

Foster Mohale, spokesperson for the National Department of Health, says the department is aware of reports of youth experiencing problems accessing PrEP at healthcare facilities.

Mohale maintains that healthcare workers are sufficiently trained to provide comprehensive HIV prevention services to all groups of people. He says that clinicians, counsellors, health promotors and peer educators have access to online training platforms. “These training modules are availed offline on flash drives to facilitate access to facilities and health care providers that do not have easy access to wifi or data to access the online version of the training materials,” he says.

Republished from Spotlight under a Creative Commons licence.

Source: Spotlight