Faecal Transplant Pills Show Promise in Clinical Trials for Multiple Types of Cancer

Two Canadian clinical trials show poop pills could help patients respond to immunotherapy while also reducing toxic side effects of cancer drugs

Faecal microbiota transplants (FMT), can dramatically improve cancer treatment, suggest two groundbreaking studies published in the prestigious Nature Medicine journal. The first study shows that the toxic side effects of drugs to treat kidney cancer could be eliminated with FMT. The second study suggests FMT is effective in improving the response to immunotherapy in patients with lung cancer and melanoma.

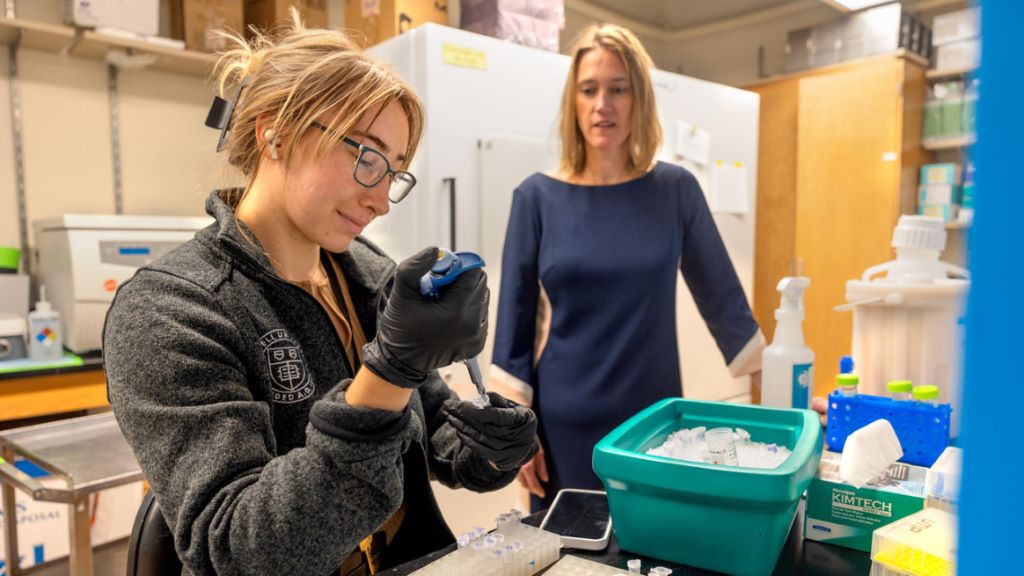

The findings represent a giant step forward in using FMT capsules – developed at Lawson Research Institute (Lawson) of St. Joseph’s Health Care London and used in clinical trials at London Health Sciences Centre Research Institute (LHSCRI) and Centre de recherche du Centre hospitalier de l’Université de Montréal (CRCHUM) – for safe and effective cancer treatment.

A Phase I clinical trial was conducted by scientists at LHSCRI and Lawson to determine if FMT is safe when combined with an immunotherapy drug to treat kidney cancer. The team found that customised FMT may help reduce toxic side effects from immunotherapy. The clinical trial involved 20 patients at the Verspeeten Family Cancer Centre at London Health Sciences Centre (LHSC).

“Standard treatment for advanced kidney cancer often includes an immunotherapy drug that helps the patient’s immune system tackle cancer cells,” says Saman Maleki, PhD, Scientist at LHSCRI. “But, unfortunately, the treatment frequently leads to colitis and diarrhoea, sometimes so severe that a patient must stop life-sustaining treatment early. If we can reduce toxic side effects and help patients complete their treatment, that will be a gamechanger.”

Separate Phase II lung and skin cancer studies were led by researchers at CRCHUM in collaboration with Lawson and LHSCRI. The studies found that 80 per cent of patients with lung cancer responded to immunotherapy after FMT, compared to only 39-45 per cent typically benefiting from immunotherapy alone. Similarly, 75 per cent of patients with melanoma who received FMT experienced a positive response to treatment, compared to only 50-58 per cent response in patients who receive immunotherapy alone. Twenty patients participated in the lung cancer clinical trial and 20 patients participated in the skin cancer clinical trial.

“Our clinical trial demonstrated that faecal microbiota transplantation could improve the efficacy of immunotherapy in patients with lung cancer and melanoma,” says Dr Arielle Elkrief, co-principal investigator and Physician Scientist, Université de Montréal-affiliated hospital research centre (CRCHUM). “The results also uncovered one possible mechanism of action of faecal transplantation – through the elimination of harmful bacteria following the transplant. Our results open up a novel avenue for personalised microbiome therapies, and faecal transplant is now being tested as part of the large pan-Canadian Canbiome2 randomised controlled trial.”

“Faecal microbiota transplantation in melanoma and lung cancer opens an entirely new therapeutic avenue, made possible by the exceptional commitment of our patients and the teamwork,” adds Dr. Rahima Jamal, Director of the Unit for Innovative Therapies (UIT) at CRCHUM. “At the Unit for Innovative Therapies (UIT) of the CRCHUM, we have had the privilege of translating laboratory discoveries into early phase clinical trials and witnessing their concrete impact on people living with cancer.”

Both studies use advanced, world-leading FMT capsules, also known as LND101, produced by Lawson in London, Ont. The research reinforces London’s place as a global leader in FMT innovation and treatment. The capsules are processed from healthy donor stools and ingested to help restore a patient’s healthy gut microbiome and treat different types of cancer.

“To use FMT to reduce drug toxicity and improve patients’ quality of life while possibly enhancing their clinical response to cancer treatment is tremendous, and it had never been done in treating kidney cancer before this,” says Dr Michael Silverman, Scientist at Lawson and Head of St. Joseph’s Infectious Diseases Program. “And none of this would be possible if not for this close collaboration: innovating the FMT capsules in Lawson labs and introducing them at LHSCRI and CHUM to advance vital research initiatives. Also, because LND101 comes from healthy donors, production can be scaled up to eventually help large numbers of cancer patients.”

The studies build on earlier London and CHUM-generated Phase I research showing FMT can safely augment treatment for people with melanoma. FMT is also being studied in people with pancreatic cancer and triple-negative breast cancer, and is already a well-established treatment for serious gut infections such as C. difficile, which can cause severe diarrhoea.

“Our hope is that our research will one day help people with cancer live longer while reducing the harmful side effects of treatment,” adds Dr Ricardo Fernandes, Scientist at LHSCRI and Medical Oncologist at LHSC. “We are world leaders in FMT research and we’re excited about its potential.”