Breathing Low-oxygen Air Slows Parkinson’s Progression in Mice

Researchers from the Broad Institute and Mass General Brigham have shown that a low-oxygen environment – similar to the thin air found at Mount Everest base camp – can protect the brain and restore movement in mice with Parkinson’s-like disease.

The new research, in Nature Neuroscience, suggests that cellular dysfunction in Parkinson’s leads to the accumulation of excess oxygen molecules in the brain, which then fuel neurodegeneration – and that reducing oxygen intake could help prevent or even reverse Parkinson’s symptoms.

“The fact that we actually saw some reversal of neurological damage is really exciting,” said co-senior author Vamsi Mootha, an institute member at the Broad, professor of systems biology and medicine at Harvard Medical School, a Howard Hughes Medical Institute investigator in the Department of Molecular Biology at Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH), a founding member of the Mass General Brigham healthcare system. “It tells us that there is a window during which some neurons are dysfunctional but not yet dead – and that we can restore their function if we intervene early enough.”

“The results raise the possibility of an entirely new paradigm for addressing Parkinson’s disease,” added co-senior author Fumito Ichinose, the William T. G. Morton professor of anesthesia at Harvard Medical School and MGH.

The researchers caution that it’s too soon to translate these results directly to new treatments for patients. They emphasize that unsupervised breathing of low-oxygen air, especially intermittently such as only at night, can be dangerous and may even worsen the disease. But they’re optimistic their findings could help spur the development of new drugs that mimic the effects of low oxygen.

The study builds on a decade of research from Mootha and others into hypoxia – the condition of having lower than normal oxygen levels in the body or tissues – and its unexpected ability to protect against mitochondrial disorders.

“We first saw that low oxygen could alleviate brain-related symptoms in some rare diseases where mitochondria are affected, such as Leigh syndrome and Friedreich’s ataxia,” said Mootha, who leads the Friedreich’s Ataxia Accelerator at Broad. “That raised the question: Could the same be true in more common neurodegenerative diseases like Parkinson’s?”

Eizo Marutani, an instructor of anesthesia at MGH and Harvard Medical School, is the first author of the new paper.

A long-standing link

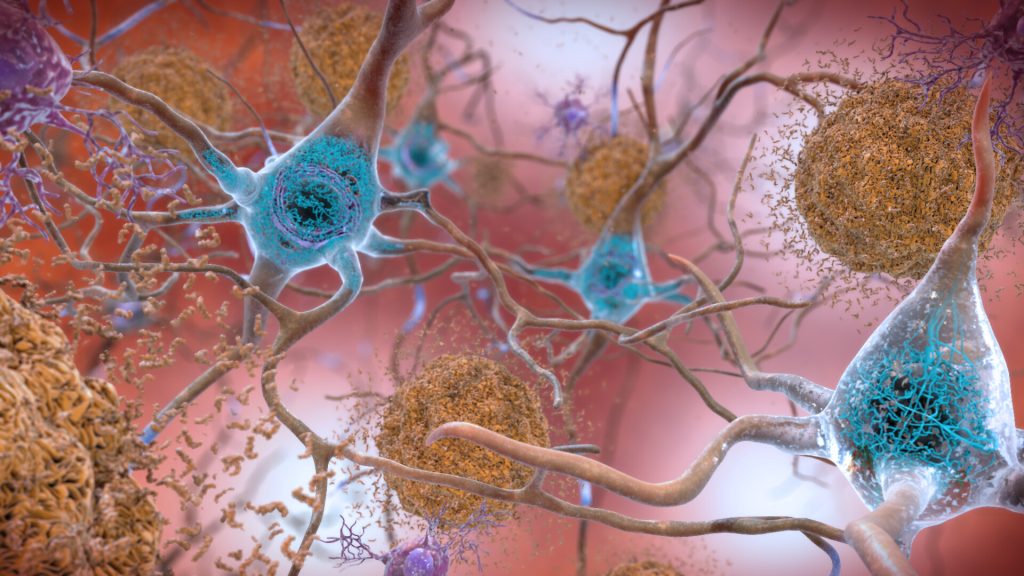

Parkinson’s disease, which affects more than 10 million people worldwide, causes the progressive loss of neurons in the brain, leading to tremors and slowed movements. Neurons affected by Parkinson’s also gradually accumulate toxic protein clumps called Lewy bodies. Some biochemical evidence has suggested that these clumps interfere with the function of mitochondria, that Mootha knew were altered in other diseases that could be treated with hypoxia.

Moreover, anecdotally, people with Parkinson’s seem to fare better at high altitudes. And long-term smokers – who have elevated levels of carbon monoxide, leading to less oxygen in tissues – also appear to have a lower risk of developing Parkinson’s.

“Based on this evidence, we became very interested in the effect of hypoxia on Parkinson’s disease,” said Ichinose.

Mootha and Ichinose turned to a well-established mouse model of Parkinson’s in which animals are injected with clumps of the α-synuclein proteins that seed the formation of Lewy bodies. The mice were then split into two groups: one breathing normal air (21% oxygen) and the other continuously housed in chambers with 11% oxygen – comparable to living at an altitude of about 4800m.

A new paradigm for Parkinson’s

The results were striking. Three months after receiving α-synuclein protein injections, the mice breathing normal air had high levels of Lewy bodies, dead neurons, and severe movement problems. Mice that had breathed low-oxygen air from the start didn’t lose any neurons and showed no signs of movement problems, despite developing abundant Lewy bodies.

The findings show that hypoxia wasn’t stopping the formation of Lewy bodies but was protecting neurons from the damaging effects of these protein clumps – potentially suggesting a new mode of treating Parkinson’s without targeting α-synuclein or Lewy bodies, Ichinose said.

What’s more, when hypoxia was introduced six weeks after the injection, when symptoms were already appearing, it still worked. The mice’s motor skills rebounded, their anxiety-like behaviors faded, and the loss of neurons in the brain stopped.

To further explore the underlying mechanism, the team analyzed brain cells of the mice and discovered that mice with Parkinson’s symptoms had much higher levels of oxygen in some parts of the brain than control mice and those that had breathed low-oxygen air. This excess oxygen, the researchers said, likely results from mitochondrial dysfunction. Damaged mitochondria can’t use oxygen efficiently, so it builds up to damaging levels.

“Too much oxygen in the brain turns out to be toxic,” said Mootha. “By reducing the overall oxygen supply, we’re cutting off the fuel for that damage.”

Hypoxia in a pill

More work is needed before the findings can be directly used to treat Parkinson’s. In the meantime, Mootha and his team are developing “hypoxia in a pill” drugs that mimic the effects of low oxygen to potentially treat mitochondrial disorders, and they think a similar approach might work for some forms of neurodegeneration.

While not all neurodegenerative models respond to hypoxia, the approach has now shown success in mouse models of Parkinson’s, Leigh syndrome, Friedreich’s ataxia, and accelerated aging.

“It may not be a treatment for all types of neurodegeneration,” said Mootha, “but it’s a powerful concept – one that might shift how we think about treating some of these diseases.”

Source: Broad Institute