Nose Drops of ‘Friendly’ Bacteria Protects Against Meningitis

Researchers have shown that nose drops of genetically modified ‘friendly’ bacteria protect against a form of meningitis.

The study, published in the journal Science Translational Medicine, was led by Professor Robert Read and Dr Jay Laver from the NIHR Southampton Biomedical Research Centre and the University of Southampton, and is the first of its kind.

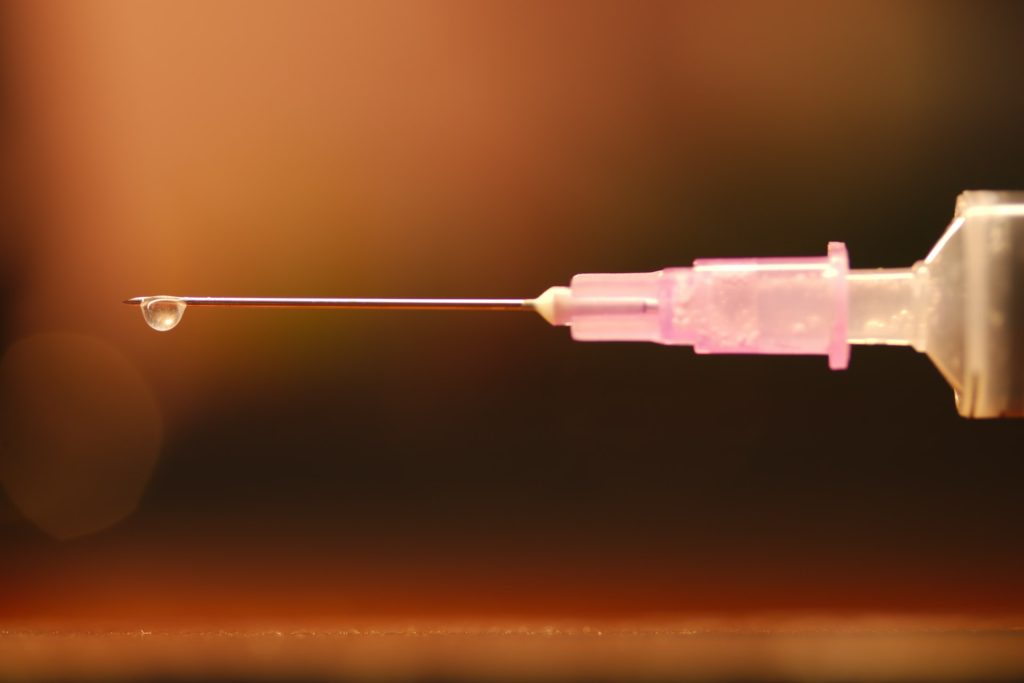

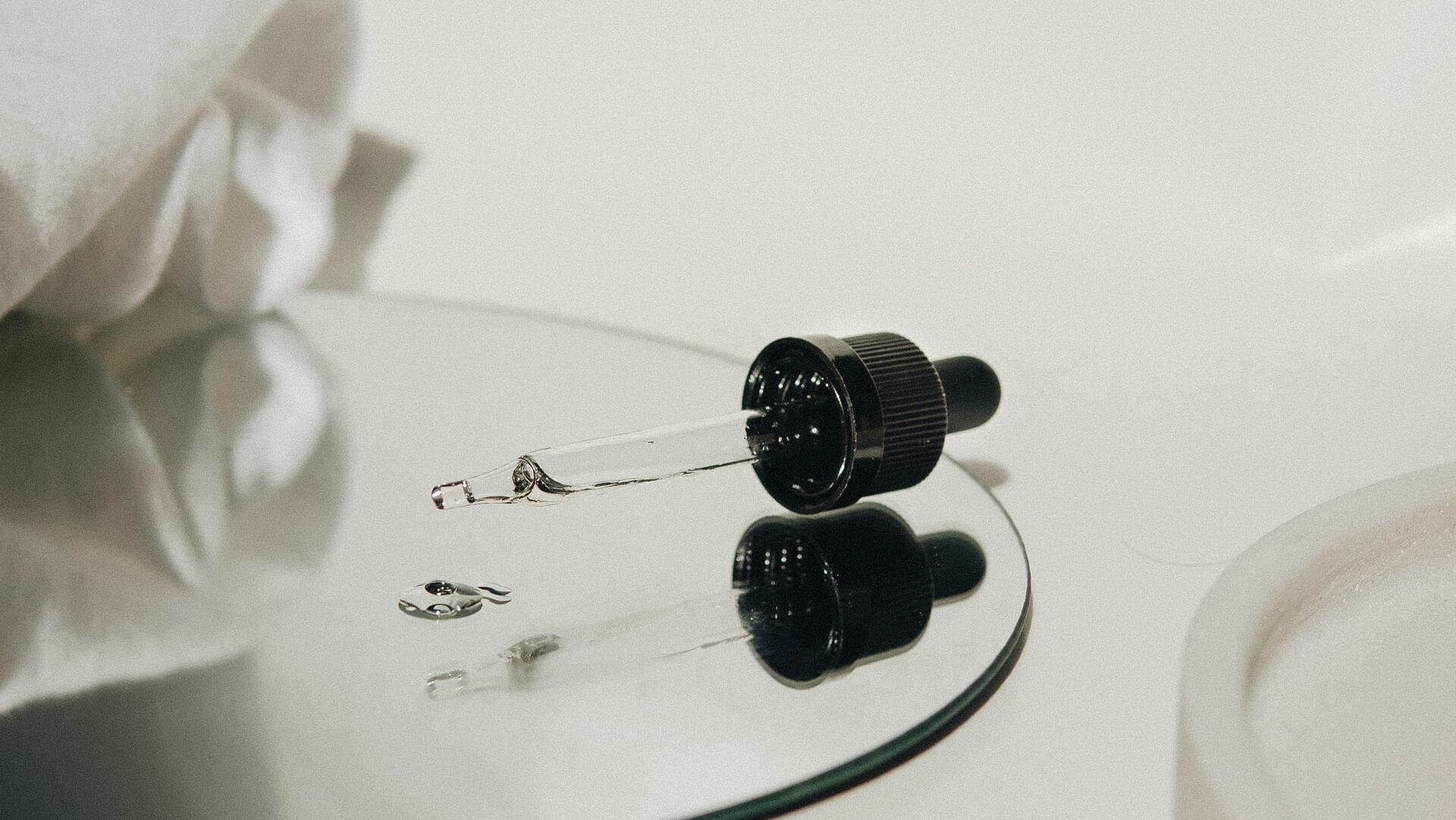

The researchers spliced a gene into a harmless bacteria type, which enabled it to remain in the nose for longer than normal, triggering an immune response. Then, via nose drops, they administered these altered bacteria into the noses of healthy volunteers. The results showed a strong immune response against bacteria that cause meningitis and long-lasting protection.

Meningitis protection

Meningitis occurs in people of all age groups but affects mainly infants, young children and the elderly. Meningococcal meningitis, a bacterial form of the disease, can lead to death in as little as four hours after symptom onset.

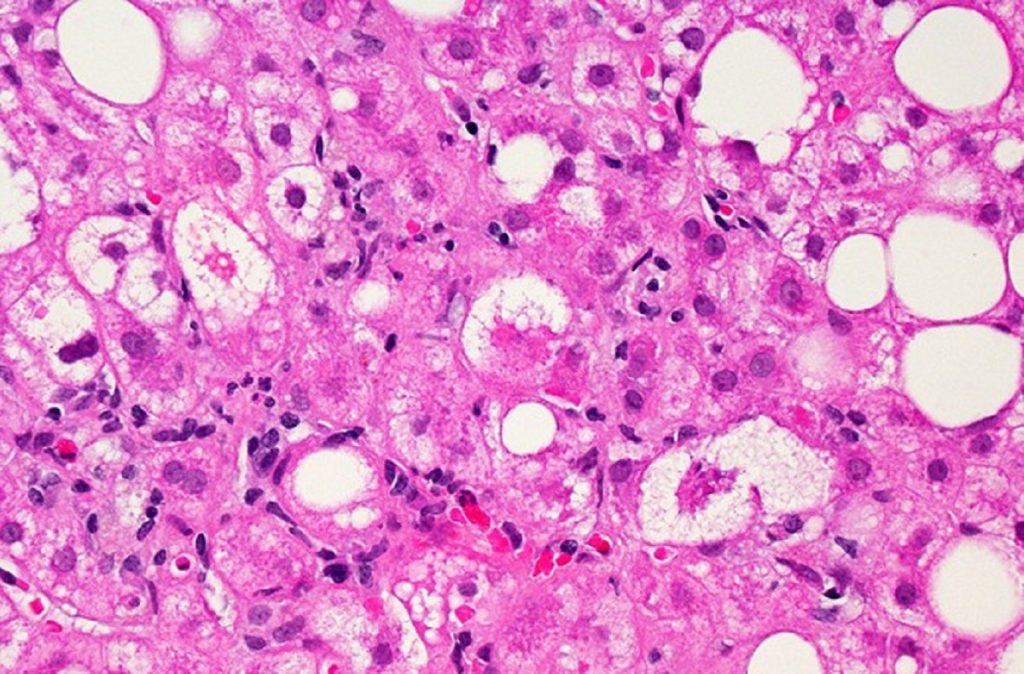

Around 10% of adults carry Neisseria meningitidis in the back of their nose and throat without any signs or symptoms. In certain people however, it can invade the bloodstream, potentially leading to life-threatening conditions including meningitis and septicaemia.

The ‘friendly’ bacteria Neisseria lactamica also lives in some people’s noses naturally. By occupying the nose, it denies a foothold to its close relative N. meningitidis.

Boosted immune response

The study is an extension of the team’s previous work aiming to exploit this natural phenomenon. Nose drops of N. lactamica in that previous study prevented N. meningitidis from settling in 60% of participants. The team sought to improve on this.

They gave N. lactamica one of N. meningitidis’ key weapons; by giving it the gene for a ‘sticky’ surface protein that grips the cells lining the nose.

Those modified bacteria managed to remain longer and produced a stronger immune response. From at least 28 days, most participants (86%) still carried it at 90 days, it caused no adverse symptoms.

This is a promising find for this new way of preventing life-threatening infections, without drugs, especially in the face of growing antimicrobial resistance.

Dr Jay Laver, Senior Research Fellow in Molecular Microbiology at the University of Southampton, commented: “Although this study has identified the potential of our recombinant N. lactamica technology for protecting people against meningococcal disease, the underlying platform technology has broader applications.

“It is theoretically possible to express any antigen in our bacteria, which means we can potentially adapt them to combat a multitude of infections that enter the body through the upper respiratory tract. In addition to the delivery of vaccine antigens, advances in synthetic biology mean we might also use genetically modified bacteria to manufacture and deliver therapeutics molecules in the near future.”

Prof Read, Director of the NIHR Southampton Biomedical Research Centre said: “This work has shown that it is possible to protect people from severe diseases by using nose drops containing genetically modified friendly bacteria. We think this is likely to be a very successful and popular way of protecting people against a range of diseases in the future.”

Source: University of Southampton

Journal reference: Laver, J.R., et al. (2021) A recombinant commensal bacteria elicits heterologous antigen-specific immune responses during pharyngeal carriage. Science Translational Medicine. doi.org/10.1126/scitranslmed.abe8573.