Preventing Drug Damage to the Vestibular System

The vestibular system is responsible for the sense of balance in the inner ear. Prolonged use of toxic substances, such as certain antibiotics or anticancer drugs, can damage the hair cells that form part of this system, leading to alterations in balance and other motor skills. Now, a team from the University of Barcelona and the Bellvitge Biomedical Research Institute (IDIBELL) has identified the genetic mechanisms involved in the degradation of the vestibular system regarding the damage caused by these ototoxic compounds that affect the vestibule. The results could help improve the diagnosis of chronic vestibular ototoxicity and other pathologies related to the hair cells of the vestibular system.

The study, published in the Journal of Biomedical Science, is led by Jordi Llorens, professor at the UB’s Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences and researcher at the Institute of Neurosciences (UBneuro) and IDIBELL. Researchers from the National Centre for Genomic Analysis (CNAG) also took part in the study.

The main causes of chronic vestibular ototoxicity are antibiotics of the aminoglycoside family, such as streptomycin – an antibiotic of choice in case of tuberculosis relapses – or anticancer drugs, such as cisplatin. Continued use of these drugs initiates a process of degeneration that causes “the hair cells to detach from the neurons, begin to deform and end up being expelled from their place in the sensory tissue,” explains Llorens.

This is a serious problem because the hair cells of the vestibular system do not regenerate. “We only have the ones we are born with. If we lose them, we also lose our balance, with very diverse consequences: from not being able to ride a bicycle to suffering blurred vision while moving, falls, orientation difficulties, dizziness or vertigo,” explains the UB professor.

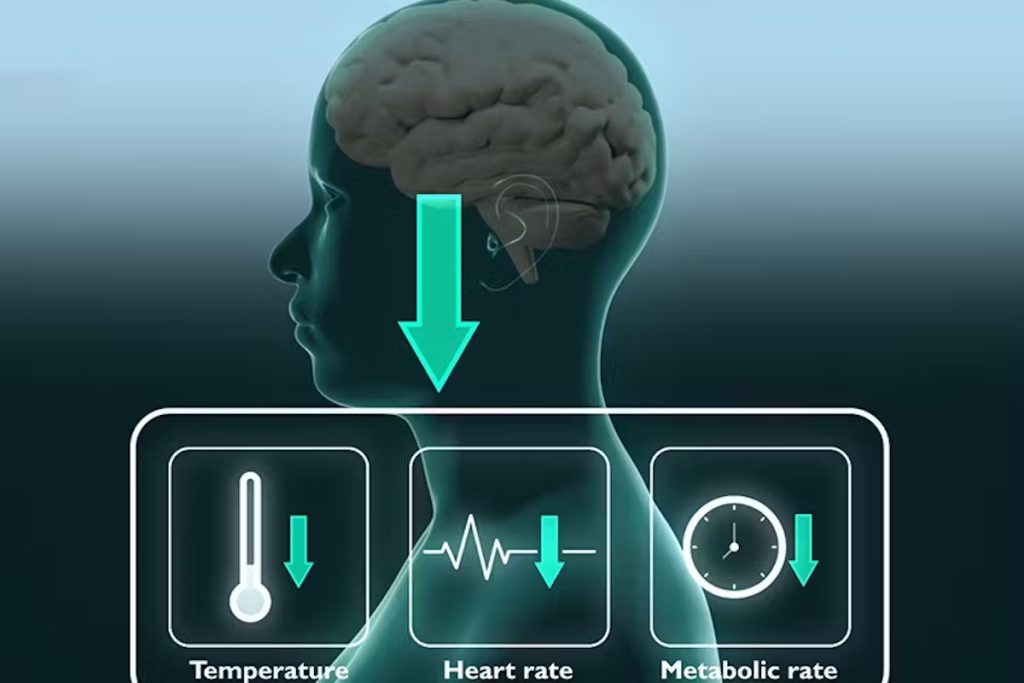

Using RNA-seq analysis, i.e. a study of the global expression of genes that reveals which genes are activated or deactivated in the tissues of the vestibular system, the researchers discovered that, in the initial stages of degeneration, the hair cells change the expression of their genes to adapt to the progressive damage caused by otototoxic drugs. “The expression of many genes that define the identity of the hair cell, i.e. those that determine its shape and its ability to respond to movement by generating the signals that are sent to the brain, is reduced,” explains Llorens.

These results, together with the fact, discovered by the researchers, that the damage is reversible during the early stages of the degeneration process, indicate that it is essential to detect the problem as early as possible to stop the toxicity and avoid irreversible damage. “Hair cells become disconnected from neurons and stop sending information to the brain, but if the toxicity is interrupted, the connections can be repaired and function is restored. This increases the chances of avoiding a permanent loss of function,” the researcher stresses.

A potential biomarker

This study may also contribute to advances in the diagnosis and treatment of the pathology, since, according to the researchers, the genetic mechanisms they have identified in response to the stress caused by ototoxic drugs will make it possible, in the future, to “measure this stress and evaluate the effect of possible therapies, such as the development of drugs capable of stopping the process of eliminating hair cells or promoting their repair.”

In addition, the study has identified a new gene, Vsig10l2, expressed by hair cells, which significantly reduces its expression in all the models analysed. “This gene is of great interest as a possible marker of chronic ototoxicity in preclinical studies,” says Llorens.

The same response to different toxics

One of the most remarkable elements of the study is that the analysis has been carried out with four different models of chronic ototoxicity, using two different animal species and two different toxins, and then cross-checking the results of all experiments.

This comprehensive analysis has allowed them to determine that the degradation process occurs in response to very different toxins. “It is not a response conditioned by a particular toxin, it is the basic response of hair cells, which is always there, in response to chronic ototoxicity of any kind,” stresses the UB professor.

These results, together with the fact, discovered by the researchers, that the damage is reversible during the early stages of the degeneration process, indicate that it is essential to detect the problem as early as possible to stop the toxicity and avoid irreversible damage.

Impact on other pathologies

The study could have implications for understanding other pathologies, as the researchers suggest that the response they have demonstrated in chronic ototoxicity might represent a general response to chronic stress of any origin. “The results could be relevant to any chronic pathology with progressive loss of vestibular hair cells, including age-related loss of vestibular function. We also hypothesise that auditory hair cells might respond in a similar way, so they could help understanding deafness,” explains Llorens.

In this sense, the research team is studying – within the framework of a project funded by La Marató de TV3 – the possible relevance of the loss of vestibular function in patients with vestibular schwannoma, a tumour of the audiovestibular nerve that appears spontaneously or as a consequence of a minority disease, neurofibromatosis type 2. “Thanks to this project, we have been able to develop a culture model that allows us to study these chronic effects or how the hair cells become progressively more damaged before dying,” he concludes.

Source: University of Barcelona