Certain Fatty Acids can ‘Supercharge’ T-Cells’ Antitumour Immunity

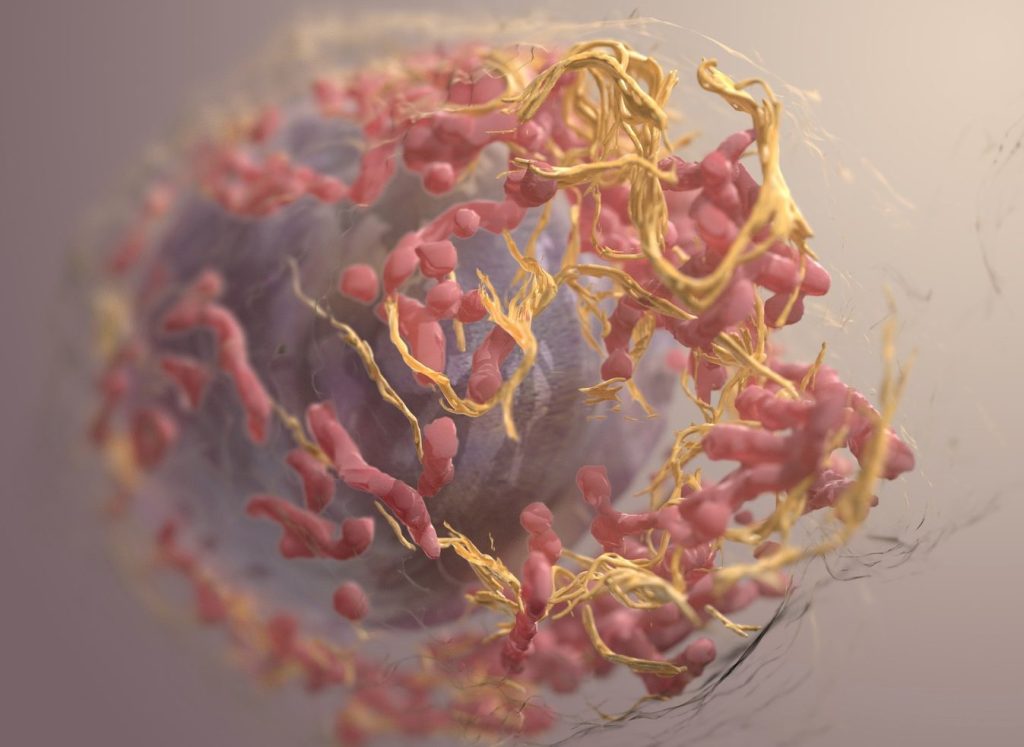

A research team at the LKS Faculty of Medicine of the University of Hong Kong (HKUMed) discovered that certain dietary fatty acids can supercharge the human immune system’s ability to fight cancer. The team found that a healthy fatty acid found in olive oil and nuts, called oleic acid (OA), enhances the power of immune γδ-T cells, specialised cells known for their cancer-fighting properties.

Conversely, they found that another fatty acid, called palmitic acid (PA), commonly found in palm oil and fatty meats, diminishes the ability of these immune cells to attack tumours. This groundbreaking study, published in the academic journal Signal Transduction and Targeted Therapy, offers an innovative approach using dietary OA supplementation to strengthen the antitumour immunity of γδ-T cells.

Dietary fatty acids and cancer immunotherapy

Dietary fatty acids are essential for health, helping with growth and body functions. They may also play a role in cancer prevention and treatment, but understanding how they affect cancer is challenging because of the complexity of people’s diets and the lack of detailed studies. Recently, scientists have learned that fatty acids can influence the immune system, especially in how it fights cancer. Specialised immune cells, called γδ-T cells, are particularly good at attacking tumours. These cells, once activated, have helped some lung and liver cancer patients live longer. However, this therapy is not effective for all patients, partly because the variation of the metabolic status, such as fatty acid metabolism, can influence its efficacy in the patients.

Oleic acid may improve cancer treatment outcomes

The research team identified a correlation between PA and OA levels and the efficacy of cancer therapies. ‘Our research suggests that dietary fatty acid supplementation, particularly with foods rich in OA, such as olive oil and avocados, could enhance γδ-T cell immunosurveillance, leading to more effective cancer treatments,’ said Professor Tu Wenwei from the Department of Paediatrics and Adolescent Medicine, School of Clinical Medicine, HKUMed, who led the study.

The team also discovered that another fatty acid, called PA, can weaken these immune cells and how OA can counteract this. ‘The results indicate that cancer patients should avoid PA and consider OA supplementation in their diets to improve clinical outcomes of γδ-T cell-based cancer therapies,’ added Professor Tu.

Significant impact from simple dietary changes

Professor Tu said, ‘This study is the first to show that the fatty acids we eat can directly affect how well our immune cells fight cancer.’ It reveals how PA can harm these cells and how OA helps them through a specific process involving a protein called IFNγ. By analysing blood samples, the researchers confirmed that the levels of these fatty acids are linked to the outcome of cancer immunotherapy.

‘For cancer patients, this discovery suggests simple changes, like eating more foods rich in OA (such as olive oil, avocados and nuts) and cutting back on PA (found in processed foods, palm oil and fatty meats), could improve the effectiveness of cancer treatments. The study also points to novel strategies, like combining dietary changes with specific drugs to further boost the immune system,’ added Professor Tu.

This study demonstrates that personalised nutrition may serve as an effective strategy to enhance immune function and support cancer treatment. It also suggests that new drugs targeting the processes affected by these fatty acids could enhance the power of γδ-T cell therapies. By integrating nutritional interventions with immunotherapy, this discovery could help more cancer patients achieve better outcomes.

Source: University of Hong Kong