Getting Vital Creatine into the Brain is a Weighty Problem

Creatine is popularly known as a muscle-building supplement, but its influence on human muscle function can be a matter of life or death. But getting it to one particular organ that needs it – the brain – is challenging.

“Creatine is very crucial for energy-consuming cells in skeletal muscle throughout the body, but also in the brain and in the heart,” said Chin-Yi Chen, a research scientist at Virginia Tech’s Fralin Biomedical Research Institute at VTC.

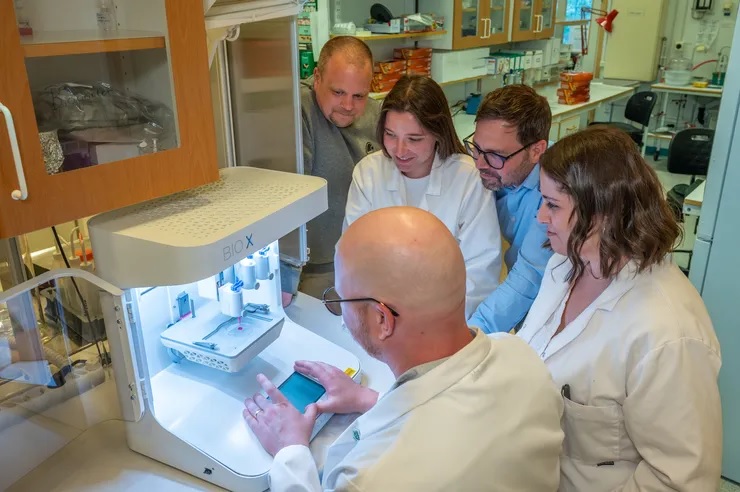

Chen is part of a research team working to develop a technique that uses focused ultrasound to deliver creatine directly to the brain. The work, being conducted in the lab of Fralin Biomedical Research Institute Assistant Professor Cheng-Chia “Fred” Wu, will be supported by a $30 000 grant from the Association for Creatine Deficiencies.

Creatine plays a vital role in the brain, where it interacts with phosphoric acid to help create the key energy molecule adenosine triphosphate (ATP). In addition to its role in energy production, creatine also influences neurotransmitter systems.

For example, creatine influences the brain’s major inhibitory pathways that use the neurotransmitter gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA), which limits neuronal excitability in the central nervous system. It may play a role in a variety of functions, including seizure control, learning, memory, and brain development.

A growing body of research suggests that creatine may itself function as a neurotransmitter, as it is delivered to neurons from glial cells in the brain and can influence signalling processes between other neurons. While creatine deficiency disorders can weaken the skeletal muscle and the heart, they can also severely affect the brain. Many patients see increased muscle mass and body weight with creatine supplements, but they often continue to face neurodevelopmental challenges that can hinder their ability to speak, read, or write.

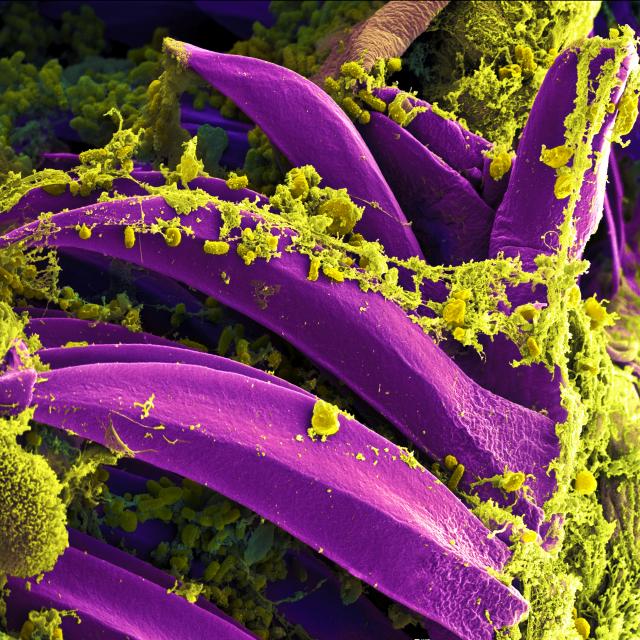

This is largely caused by the brain’s protective blood-brain barrier preventing creatine entry.

Wu studies therapeutic focused ultrasound, which precisely directs sound waves to temporarily accessed areas of the brain. The process allows drugs to reach diseased tissue without harming surrounding healthy cells. While Wu is investigating this method as a potential treatment for paediatric brain cancer, he also sees potential in applying it to creatine deficiency.

“Through the partnership between Virginia Tech and Children’s National Hospital, I was able to present our work in focused ultrasound at the Children’s National Research & Innovation Campus,” Wu said. “There, I met Dr Seth Berger, a medical geneticist, who introduced me to creatine transporter deficiency. Together, we saw the promise that focused ultrasound had to offer.”

The Focused Ultrasound Foundation has recognised Virginia Tech and Children’s National as Centers of Excellence. Wu said the two organisations bring together clinical specialists, trial experts, and research scientists who can design experiments that could inform future clinical trials.

“It was a moment that made me really excited – that I had found a lab where I could move from basic research to something that could help patients,” Chen said. “When Fred asked me, ‘Are you interested in this project?’ I said, ‘Yes, of course.’”

Because creatine deficiencies can impair brain development, the early stages of Chen’s project will concentrate on using focused ultrasound to deliver creatine across the blood-brain barrier. Chen hopes the technique will restore normal brain mass in models of creatine deficiency.

Source: Virginia Tech