Antibiotic Resistance is Putting SA’s Newborns at Risk

By Sue Segar

Experts say bacterial infections are responsible for more infant deaths than is generally recognised, and things may get worse as more of the bugs become resistant to commonly used antibiotics. We asked local experts about this growing threat to newborns.

A two-week-old baby is referred to the Red Cross War Memorial Children’s Hospital (RCWMCH) in Cape Town. The infant, who was born prematurely at six months, has come from a nearby neonatal hospital.

She’s developed complications, including a feed intolerance and constant vomiting. On investigation, she is found to have a bowel perforation and a condition called necrotising enterocolitis. Surgeons conclude she needs an operation to repair the perforation. A sample of pus from inside her abdomen is sent to a laboratory to identify any infections. While the tests are being done, the infant is started on second-line antibiotics. The doctors suspect she picked up an infection due to pathogens that may be resistant to first-line antibiotics while in the neonatal hospital.

“But 48 hours later, when the results are available, they may show that the antibiotics we’ve been treating the baby with are not treating the bacteria that have now been detected in the lab,” says Associate Professor James Nuttall, a paediatric infectious diseases sub-specialist at RCWMCH and the University of Cape Town.

“In response to those results, we’d change to a different set of antibiotics to try and target the bacteria that have been detected. In the meantime, the child has deteriorated and requires a second operation. Throughout all the subsequent treatments, we are testing samples for infections she might – and frequently will – acquire along the way.”

From then on, he says it’s a case of trying to keep up with the sequence of infections that the baby might develop. Some of these infections may have originated at the neonatal hospital, while others could have been acquired during her treatment in the Intensive Care Unit (ICU) at RCWMCH, possibly from the operating theatre, intravenous lines, or healthcare workers’ hands.

“This is the kind of scenario we are faced with all the time,” says Nuttall. “The fact is, an infant might come into hospital with one infection and, unfortunately, pick up a bunch of other infections while in the hospital from transmission of pathogens that may be resistant to one or more of the commonly used first- or second-line antibiotics.”

Sitting in a boardroom at the Red Cross Hospital, close to the paediatric wards and clinics in which he treats sick children referred from other hospitals in Cape Town and beyond, Nuttall says there are two possible outcomes for this baby.

“She might turn the corner and respond to the new antibiotics, together with interventions from the surgical doctors and expert management in an ICU. Or she might not respond to the treatment, and die two days later, because of ongoing infection that doesn’t respond to treatment.”

Nuttall is discussing the ongoing issue of rising antibiotic resistance, particularly among neonates, the group most vulnerable to this. He’s responding to Spotlight’s main question: Will the antibiotics used to treat bacterial infections, such as Klebsiella pneumoniae – which have seen hundreds of babies die in hospitals in recent years – keep working? And, how big is the risk of antibiotic resistance to infants?

“The short answer to whether the antibiotics we currently use to treat bacterial infections will keep working is no,” he says.

‘Almost endemic’

In some South African healthcare facilities, especially in the public sector, antibiotic-resistant bacteria have become “almost endemic”, says Professor Shabir Madhi, director of the Wits Vaccines and Infectious Diseases Analytics Unit at University of Witwatersrand (WITS VIDA).

“There are a large number of deaths occurring on an ongoing basis. We still have clusters of outbreaks, but those are underpinned by a really widespread dissemination of these antibiotic-resistant bacteria, and persistently high rates of hospital-acquired infections, especially in the first month of life,” he says. “Despite the best of efforts, we haven’t been able to get on top of this.”

Madhi headed up a study at the Chris Hani Baragwanath Academic Hospital in Soweto in which they used molecular testing to look at evidence of infections in 153 babies who had passed away. The researchers found that infections were the immediate or underlying cause of death in 58% of all the neonatal deaths, including the immediate cause in 70% of neonates with complications of prematurity as the underlying cause.

Overall, 74.4% of 90 infection-related deaths were hospital-acquired, mainly due to multidrug-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii (52.2%), Klebsiella pneumoniae (22.4%), and Staphylococcus aureus (20.9%).

Also asked whether the antibiotics used to treat Klebsiella and other bacterial infections will keep working, Madhi says: “The short answer is that we’ve already run out of antibiotics in the public sector that can treat all of these different bacteria.”

He says that there are two bacteria that are of particular concern in South Africa.

“The one is Klebsiella pneumoniae, which that has become resistant to almost all of the antibiotic classes that are available for use, except perhaps for colistin, (a reserve antibiotic which is seen as a last-resort treatment for multidrug-resistant Gram-negative infections), but even antibiotic resistance to colistin in bacteria is emerging.

“The other big one is Acinetobacter baumannii, which is also a common cause of hospital-acquired infections. Here the bacteria have become resistant to all classes of antibiotics including colistin.”

Madhi says compared to other African countries, South Africa is better equipped to provide high-level care, including intensive care, to prematurely-born babies.

“Consequently, we end up spending a mini fortune to get these very premature children to survive the first few days of life, only for them then to succumb to hospital-acquired infections. Whereas in other settings many of these babies will die in the first few hours of life.”

He adds: “The single leading cause of neonatal mortality in South Africa is antibiotic resistant bacterial infections, but that is underpinned by other conditions which increases the susceptibility of babies to eventually succumb to these hospital-acquired infections.”

In the public sector, Madhi says hospital-acquired infections are a major reason why children are dying. In the private sector, there is more attention on identifying these infections, along with better resources, which helps reduce the problem.

Meanwhile, physicians like Nuttall are put in impossible situations at Red Cross.

“When doing blood tests on an infant to check for infection, you can’t wait for those results. You have to start treatment with what you think is the appropriate treatment. That’s the empirical treatment,” explains Nuttall.

“Then, when you isolate a bacterium and know its resistance profile (or antibiotic susceptibility profile), you must redirect your treatment to what’s known as ‘directed’ or definitive treatment. But there’s now been a time gap of 24 to 72 hours where the infant is on treatment, and you don’t know if it’s the right treatment. That’s a critical issue, because the baby might deteriorate in that time because they’re not on the right treatment,” he says.

He says the choice of empiric antibiotics is becoming more difficult, “as what we previously used as empiric antibiotic treatment is less and less reliable to treat serious infections, particularly in patients who acquire resistant infections in hospital”.

In a position paper, Nuttall and his colleagues write that growing antibiotic resistance is linked to the increased use of “reserve” and “watch” antibiotics. The WHO classifies antibiotics into three groups. Access antibiotics are the common ones used to treat everyday infections in the community. Watch antibiotics are broad-spectrum antibiotics that carry a higher risk of causing resistance, so their use must be carefully monitored and limited. Reserve antibiotics are last-resort treatments for infections caused by multi-drug-resistant bacteria and should only be used when all other options have failed.

‘Totally underestimated’

Following the research described earlier, Madhi says they convened an expert panel, to deliberate on what the causes of death was in children.

Unfortunately, he says, it’s become completely monotonous in that there’s a clear series of events for children born prematurely, who die: They’re admitted to hospital, they usually require ICU, they improve in ICU, and two to three days later, they appear very sick again. “Often you don’t actually identify the bacteria causing the clinical deterioration when you investigate ante-mortem, and you only realise the child actually succumbed to antimicrobial resistant bacterial infections after you’ve done the postmortem sampling”. Postmortem sampling is not done systematically across the country.

“What the post-mortem sampling has unmasked, is that we’ve totally underestimated the contribution of antibiotic-resistant bacteria in relation to causes of neonatal death. If we were to do the same investigations in other facilities, there would be much greater heightened awareness of what is really an unrecognised endemic public health crisis across our healthcare facilities,” says Madhi.

Professor Angela Dramowski, Head of the Clinical Unit: General Paediatrics at Tygerberg Hospital, agrees that outbreaks in low- and middle-income country hospitals, including South Africa are under-reported.

“What we see in the literature and in the headlines of newspapers is the tip of the iceberg. The vast majority of outbreaks in fact are either undetected or unreported. This is almost an invisible problem because a lot of the deaths are currently labelled due to another cause, for example, prematurity.

“This is a crucial public health crisis. We cannot practice modern medicine without effective antibiotics, and, especially for newborns the situation is perilous as we have very few effective treatment options left.”

‘Existential threat’

Though more acute in some areas, the problem is a global one. Marc Mendelson, Professor of Infectious Diseases at the University of Cape Town, describes antibiotic resistance as an existential global health threat.

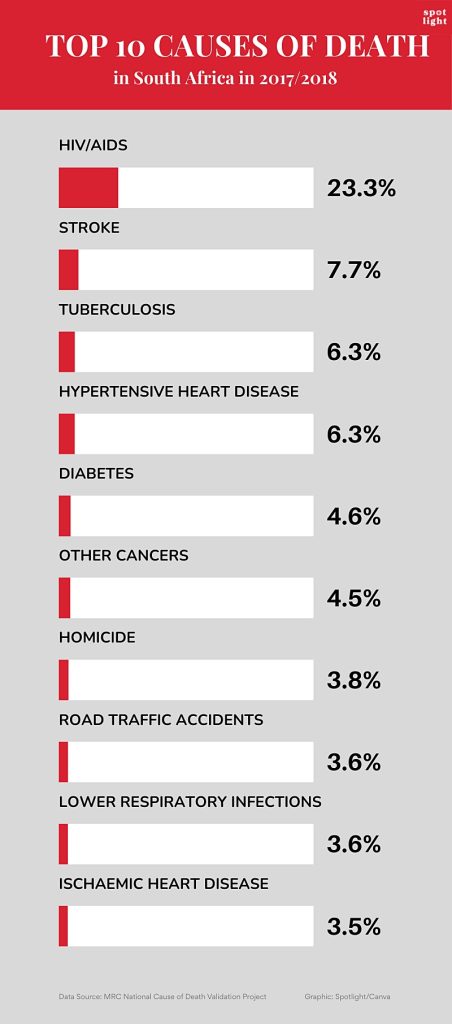

“If antibiotic resistance is not mitigated, in the next 25 years, 39 million people globally will die of an antibiotic-resistant bacterial infection. That will dwarf HIV, tuberculosis, and malaria,” he says.

“There are bacteria currently causing infections in our hospitals in South Africa that are totally resistant to antibiotics. Those patients would usually die or need extraordinary measures to keep them alive such as amputating a limb to remove the infection in a bone or joint,” Mendelson says.

“People have always assumed if you get sick with a bacterial infection, there will be an antibiotic to treat it. Doctors in and out of hospitals have been too lax in how they prescribe antibiotics. Now we’re paying the price as some bacterial infections are not easily treatable,” he says.

As Dramowski points out, there is a lot of good science confirming the extent of the problem. A systematic review published in The Lancet found that almost 5 million deaths in 2019 were associated with bacterial infections resistant to antibiotics.

“That huge number is more than deaths from HIV and malaria combined,” she says.

Dramowski also points to another review study that found 3 million cases of neonatal sepsis globally each year, with at least 570 000 deaths (likely an underestimate). Over 95% of deaths from neonatal antibiotic resistance occur in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs).

“In a nutshell, in five big studies … they showed that antibiotic resistance to the World Health Organization-recommended antibiotic treatments ranges anywhere between 40 to 70%, so almost half of all babies with severe bacterial infection have resistance to the recommended antibiotic treatment,” she says.

What to do?

To address the major issue of antibiotic resistance in infants, Dramowski stresses the importance of prevention. This includes improving Water, Sanitation, and Hygiene (WASH) as well as Infection Prevention and Control programmes to reduce the spread of antibiotic-resistant bacteria in communities and healthcare facilities. She also stresses the need to prevent pre-term births as much as possible, as hospital admissions carry a high risk of acquiring antibiotic-resistant bacteria and developing infections.

She says increased surveillance of infections in LMICs is also crucial, along with more antibiotic trials to provide better alternatives. Additionally, there is a strong need for responsible antibiotic use (stewardship) to ensure they are only used when necessary, helping to prevent the development of antibiotic resistance.

A challenge in practicing stewardship is the difference in resources between the public and private sectors, says Professor Vindana Chibabhai, Head of the Centre for Healthcare-associated Infections, Antimicrobial Resistance, and Mycology (CHARM) at the National Institute for Communicable Diseases. Expensive antibiotics are more easily accessible in the private sector, while they are often not available in the public sector.

“Antibiotic stewardship is happening all over the country but we need to have a national monitoring system,” she says.

Chibabhai says that private sector clinicians often work independently and are not required to follow stewardship programmes as strictly as those in public sector hospitals. To address antibiotic resistance, she says we need monitoring systems to track the effectiveness of these programmes and provide support to hospitals struggling with them. Even though some hospitals have dedicated pharmacists, microbiologists, and clinicians, Chibabhai says they may need additional help to strengthen their antibiotic stewardship efforts.

‘Lots of lovely paper’

A major issue highlighted by experts is the lack of a clear AMR strategy in South Africa. The last strategy, which covered 2019 to 2024, was not funded, and its impact has not been evaluated.

“We have lots of lovely paper and lots of committed people doing great work but in terms of interventions, none of it is funded,” says Mendelson, who chaired the Ministerial Advisory Committee on Antimicrobial Resistance for the eight years until 2022. “If these interventions were funded, we could save lives.”

Madhi says the consequences of not implementing South Africa’s AMR plan are exactly what we are seeing now. “The problems have become endemic and entrenched in public healthcare facilities and lead to large numbers of unnecessary deaths which could have been prevented if we implemented a proper strategy in place.”

He says the situation now calls for a multi-faceted approach. “It’s not just about the type of antibiotics that should be available but about mitigating the many contributing factors that resulted in these outbreaks. That requires immense investment in terms of resources and expertise.”

Republished from Spotlight under a Creative Commons licence.

Read the original article.