Why did Nobody Catch the Flu in a Transmission Experiment?

Researchers from University of Maryland Schools of Public Health and Engineering in College Park and the School of Medicine in Baltimore wanted to find out how the flu spreads, so they put college students already sick with the flu into a hotel room with healthy middle-aged adult volunteers. The result? No one caught the flu.

“At this time of year, it seems like everyone is catching the flu virus. And yet our study showed no transmission – what does this say about how flu spreads and how to stop outbreaks?” said Dr Donald Milton, professor at SPH’s Department of Global, Environmental and Occupational Health and a global infectious disease aerobiology expert who was among the first to identify how to stop the spread of COVID-19.

The study, out in PLOS Pathogens, is the first clinical trial in a controlled environment to investigate exactly how the flu spreads through the air between naturally infected people (rather than people deliberately infected in a lab) and uninfected people. Milton and his colleague Dr Jianyu Lai have some ideas about why none of the healthy volunteers contracted the flu.

“Our data suggests key things that increase the likelihood of flu transmission – coughing is a major one,” said Lai, post-doctoral research scientist, who led data analysis and report writing for the team.

The students with the flu had a lot of virus in their noses, says Lai, but they did not cough much at all, so only small amounts of virus got expelled into the air.

“The other important factor is ventilation and air movement. The air in our study room was continually mixed rapidly by a heater and dehumidifier and so the small amounts of virus in the air were diluted,” Lai said.

Lai adds that middle-aged adults are usually less susceptible to influenza than younger adults, another likely factor in the lack of any flu cases.

Most researchers think airborne transmission is a major factor in the spread of this common disease. But Milton notes that updating international infection-control guidelines requires evidence from randomised clinical trials such as this one. The team’s ongoing research aims to show the extent of flu transmission by airborne inhalation and exactly how that airborne transmission happens.

The lack of transmission in this study offers important clues to how we can protect ourselves from the flu this year.

“Being up close, face-to-face with other people indoors where the air isn’t moving much seems to be the most risky thing – and it’s something we all tend to do a lot. Our results suggest that portable air purifiers that stir up the air as well as clean it could be a big help. But if you are really close and someone is coughing, the best way to stay safe is to wear a mask, especially the N95,” said Milton.

The team used a quarantined floor of a Baltimore-area hotel to measure airborne transmission between five people with confirmed influenza virus with symptoms and a group of 11 healthy volunteers across two cohorts in 2023 and 2024. A similar quarantine set-up was used in an earlier study and exhaled breath testing was used in several pioneering studies by Milton and colleagues on influenza transmission.

During the most recent flu study, participants lived for two weeks on an isolated floor of the hotel, and did daily activities simulating different ways that people gather and interact – including conversational ice-breakers, physical activities like yoga, stretching or dancing. Infected people handled objects such as a pen, tablet computer and a microphone, before passing the objects among the whole group.

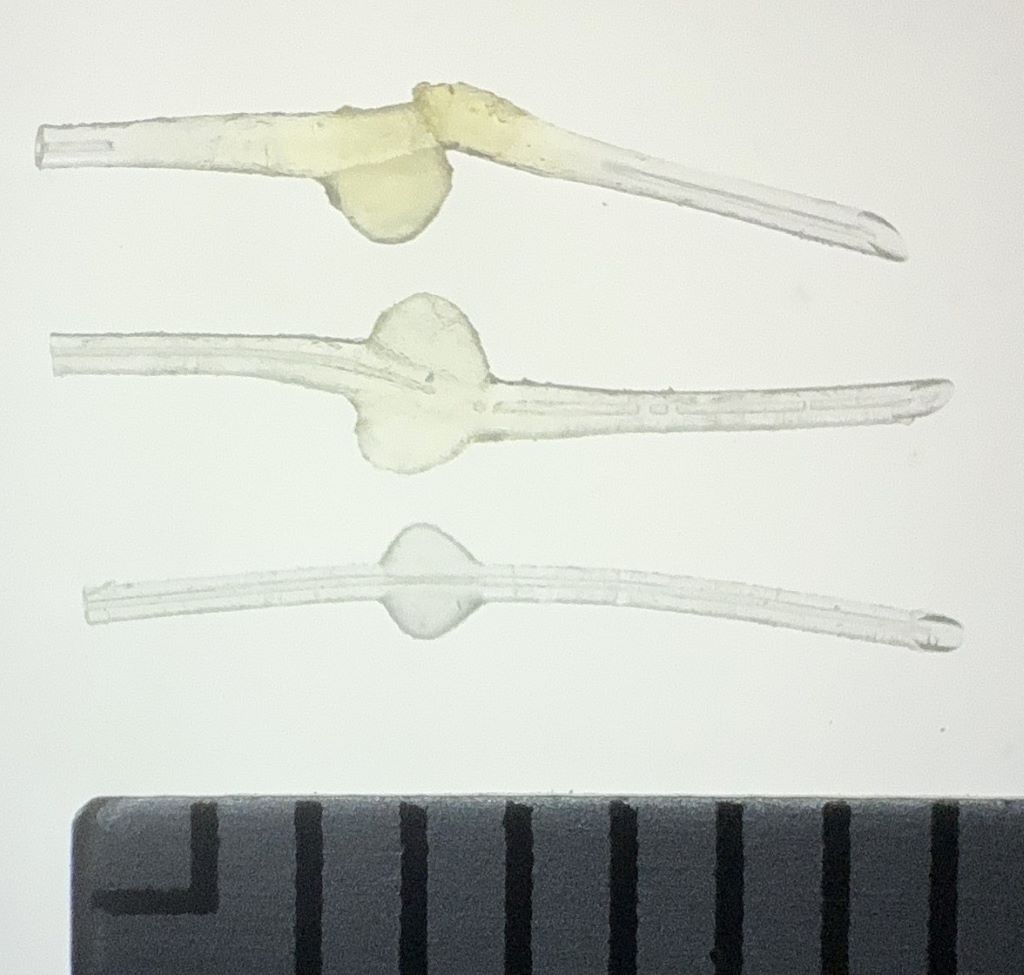

Researchers measured a wide range of parameters throughout the experiment, including participant symptom monitoring, daily nasal swabs and saliva samples and blood collection to test for antibodies. The study measured the viral exposure in volunteers’ breathing area as well as the ambient air of the activity room. Participant exhaled breath was also measured daily in the Gesundheit II machine, invented by Milton and colleagues at Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health.

Finding ways to control flu outbreaks is a public health priority, says Milton. Flu is responsible for a considerable burden of disease in the United States and globally – up to 1 billion people across the planet catch seasonal influenza every year and this season has seen at least 7.5 million flu cases so far in the United States alone, including 81 000 hospitalisations and over 3000 deaths.

Source: University of Maryland