A Vaccine Wake-up Call for South Africa

Time to work together to close vaccine gap putting children and communities at risk

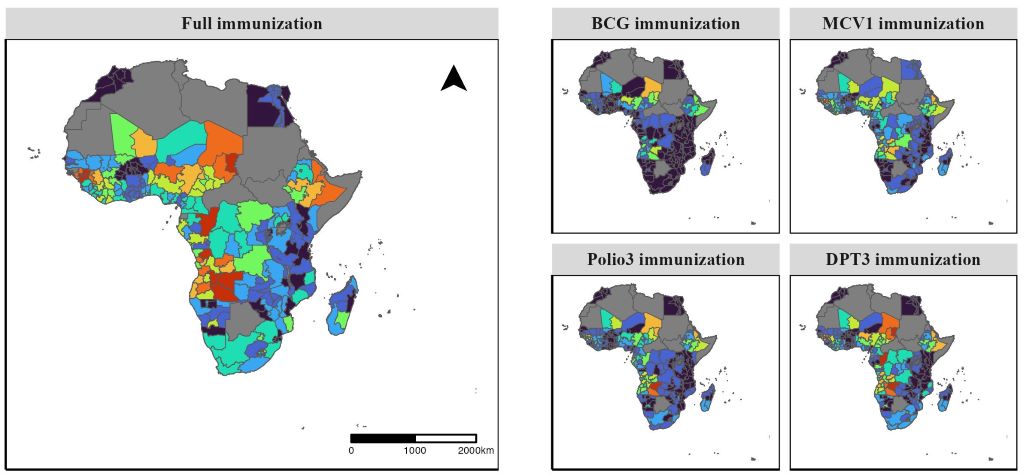

South Africa is facing a growing public health concern, as large numbers of children1 miss out on life-saving vaccinations.

According to Dr Zeina Elian, Vaccines Medical Head for Sanofi Africa, the country is seeing a resurgence in ‘zero dose’ communities. These are areas where children have not received a single routine vaccine. In low dose communities, under-immunisation is similarly leaving many children at risk for preventable diseases.

“We are seeing entire groups of children falling through the cracks,” says Dr Elian. “If these children remain unvaccinated, diseases we thought were under control can, and will, return.”

What is a ‘zero dose’ child?

A ‘zero dose’ child is one who has not received any of the vaccines scheduled under South Africa’s national Expanded Programme on Immunisation (EPI). “In these communities, children miss out on all opportunities for protection, leaving them vulnerable to highly contagious and often dangerous diseases like diphtheria, pertussis (whooping cough) and measles,” says Dr Elian.

Recent data shows South Africa had 220 000 zero-dose children1 in 2023, ranking it among the top 20 countries globally with the highest number of unvaccinated children. “We’ve seen outbreaks of whooping cough in the past year and are currently experiencing a rise in diphtheria cases. These diseases are preventable. Their return points directly to gaps in coverage,” says Dr Elian.

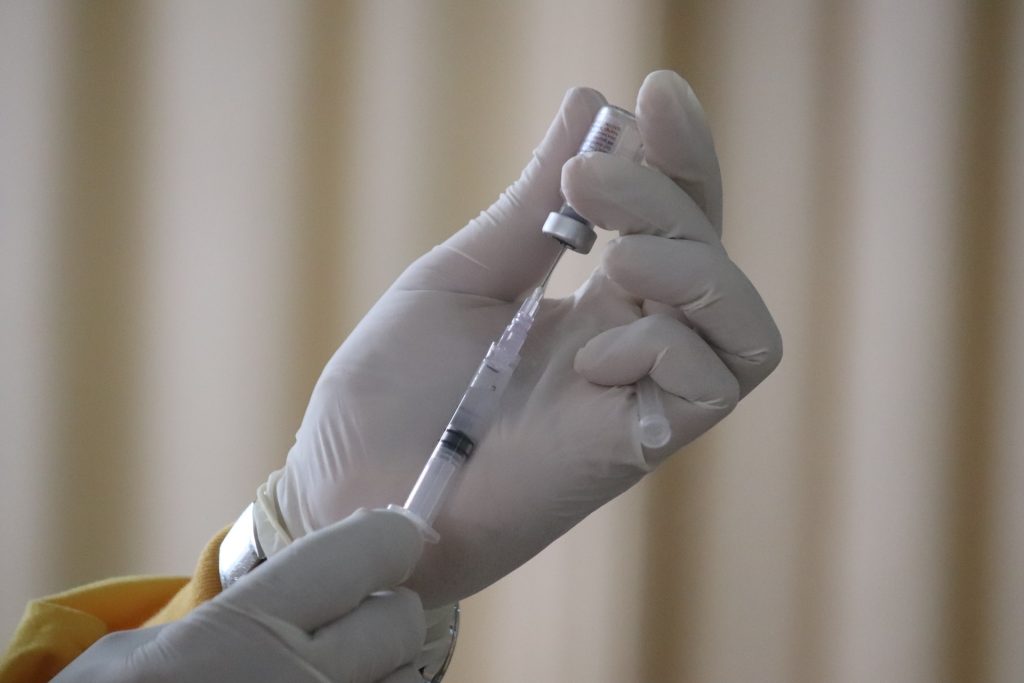

Role of the health care provider

Health care providers play a crucial role in catch-up vaccination. They identify patients who are behind on their vaccines, explain the importance of protection, and address concerns with clear, trusted information. With the right training and guidelines, they create safe and supportive environments where patients feel comfortable catching up on missed doses. By confidently recommending and administering vaccines, providers help close immunity gaps and protect both individuals and the wider community.

Vaccine hesitancy and misinformation put lives at risk

“Vaccine hesitancy and the spread of misinformation are undermining immunisation efforts. False information spreads faster than facts. Rebuilding trust in vaccines is crucial, not just to protect individuals, but to protect entire communities through herd immunity,” says Dr Elian.

Herd immunity means that when most people in a community are vaccinated, it becomes much harder for diseases to spread. This protects everyone, especially babies, the elderly, and people with health conditions who can’t get vaccinated themselves.

Dr Elian also stresses that we need to take flu more seriously. “We don’t talk enough about flu. People think it’s just a seasonal thing or a mild illness, but flu can be serious, especially for pregnant women, the elderly and people with chronic conditions. Every year, we have people ending up in hospital with flu complications. It’s vaccine-preventable, and yet uptake remains low.”

Immunisation is important at every stage of life

Vaccination is a lifelong health strategy, not just a childhood milestone. Dr Elian says that life-course immunisation means starting with vaccines during pregnancy and continuing through all stages of life. The aim is to protect people at the times they are most vulnerable, a need that changes as we age.

Key examples include:

- Pregnant women: flu and whooping cough vaccines

- Adolescents: HPV, tetanus, diphtheria and pertussis boosters

- Young adults: meningococcal vaccines for students and military recruits

- Adults: pertussis boosters every 5 to 10 years, especially for those with asthma or COPD

- Older adults: annual flu vaccines and pneumococcal vaccines to prevent serious complications

According to the latest National Institute for Communicable Diseases (NICD) alert, in the current diphtheria outbreak2, 70% of cases occurred in adults, and the case-fatality rate was 21%. “These are not just childhood diseases,” says Dr Elian. “Adults are clearly vulnerable too. Lifelong immunisation must become standard in South Africa.”

Dr Elian adds that public and professional attitudes need to change.

“Every health appointment is a chance to check vaccine status. Not just for kids, but for parents, grandparents, students and workers. It’s a shift in culture, where we all become more proactive about protecting our health.”

Falling vaccination rates carry a heavy economic cost

While routine vaccines are free in the public system, indirect barriers such as time off work and transport costs persist. But the economic cost of illness is often much higher.

“Missing a day of work to vaccinate a child may feel like a loss, but missing five days to care for a sick child is far worse,” says Dr Elian. “For adults, illness can mean lost income, expensive treatment and even hospitalisation. At a national level, low vaccination coverage fuels more frequent and severe outbreaks, forcing costly catch-up campaigns, increasing the need for surveillance, and placing added strain on already stretched health systems. The economic toll includes reduced productivity and higher healthcare expenditure, making prevention through vaccination the far more cost-effective option.”

Act now to keep yourself, your family and community safe

Take a more active role in your health by speaking to healthcare professionals. “Every visit to the clinic or doctor is an opportunity to ask, ‘What vaccines do I need?’ ‘What about my children?’, ‘What’s recommended for my age or condition?’, ‘Am I up to date on my vaccines?’ That one question could prevent serious illness or even death,” says Dr Elian.

Dr Elian also advises parents and caregivers to check their children’s Road to Health booklets to ensure vaccines are up to date, especially before school entry.

“Vaccines save lives. They prevent suffering and they protect the people around us. But only if we use them.”

Quick facts

- Since 1974, the Expanded Programme on Immunisation has saved more than 50 million lives3 across Africa.

- Vaccines protect against serious diseases like diphtheria, pertussis (whooping cough), measles, flu, and more.

- Childhood vaccines are free at public clinics.

- South Africa is currently experiencing preventable disease outbreaks due to low vaccination rates.

- Everyone has a role to play in preventing illness – parents, students, healthcare workers, and older adults.

Ask your healthcare provider if you’re due for a vaccine or booster.

References

1. Global updates on vaccination uptake 29 April 2025. Available from: https://knowledgehub.health.gov.za/system/files/2025-05/Global%20updates%20on%20vaccination%20uptake_final.pdf

2. NICD Diphtheria situational report (week 32 of 2025). Available from: https://www.nicd.ac.za/diphtheria-situational-report-week-32-of-2025

3. Africa Vaccination Week 2025: Message from Ms Shenaaz El-Halabi, WHO South Africa Representative | WHO | Regional Office for Africa. Available from: https://www.afro.who.int/countries/south-africa/news/africa-vaccination-week-2025-message-ms-shenaaz-el-halabi-who-south-africa-representative