EDITORIAL | The Rot Runs Deep: Gauteng Health’s Dance of Impunity Betrays the People It Is Meant to Serve

Spotlight Editors

The courts have spoken. The health ombud has issued devastating reports. The Auditor-General has again put damning evidence on the table. Civil society has protested. Yet, the devastating crisis in Gauteng’s health system shows no sign of improvement.

The rot in Gauteng appears to be deepening. Nowhere is this more evident than in the province’s health department, which remains trapped in a cycle of institutional decay and administrative failure.

The consequences are catastrophic, with real and devastating impacts on lives and the delivery of essential health services.

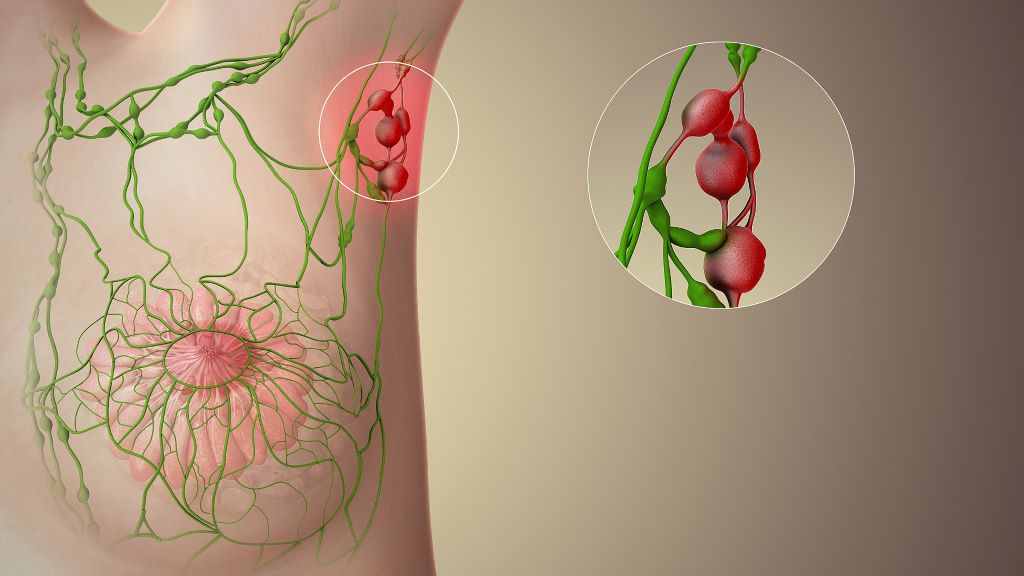

A case in point is the department’s failure to provide life-saving treatment to cancer patients. In a stunning rebuke, a high court found this failure unlawful and unconstitutional. Rather than comply with its constitutional obligations, Health MEC Nomantu Nkomo-Ralehoko and the health department chose to appeal the judgment to the Supreme Court of Appeal.

Making matters worse, a second high court ruling ordered the department to implement the original judgment. And yet again the department is appealing.

Jack Bloom, a DA MP in Gauteng, suggests that the MEC and the department is fighting so hard because they may eventually be held accountable in a case he says evokes the horrors of the Life Esidimeni tragedy. Bloom may have a point.

The background is dismaying.

Prior to the recent court rulings on cancer care, sustained pressure from activists had helped the department secure a R784 million budget for outsourcing radiation oncology services. But the department returned the first tranche of R250 million to Treasury unspent.

At last count in 2022, more than 3 000 patients were on a waiting list for treatment. Many of them would by now have lost their lives. Others may still be alive, but the optimal time for them to get radiation therapy may have passed and their chances of survival are thus substantially diminished.

That R250 million meant to help these desperate people and families simply went unspent boggles the mind.

It is no doubt too late for many, but there are at least some limited signs of progress. While the department has not been answering Spotlight’s questions, Nkomo-Ralehoko has indicated in the Gauteng legislature that a significant number of cancer patients are being treated with the help of private sector facilities. That the MEC and the department is nevertheless challenging the high court ruling, much of which is a demand for greater transparency, suggests that they know they have at best taken several more steps back than they have taken forward.

Unfortunately, none of this feels new.

For well over a decade, Spotlight and other media have reported on a persistent pattern of institutional breakdown and failed leadership in Gauteng’s public healthcare system. Among the most shocking examples are the Life Esidimeni tragedy, the assassination of whistleblower Babita Deokaran, and the state’s sluggish response to the corruption she exposed. Questions continue to swirl around an impasse over a critical agreement with Wits to bolster healthcare services, senior appointments in the department and the selection of hospital CEOs. The fire at Charlotte Maxeke Johannesburg Academic Hospital and the lack of urgency in restoring services there further underscores the dysfunction. So does the persecution of whistleblowers like Dr Tim de Maayer, and the damning Health Ombud report into conditions at Rahima Moosa Mother and Child Hospital.

And that’s just the tip of the iceberg. Years of chaos in hospital security contracts, questionable food procurement practices, and the department’s failure to supply adequate colostomy bags to patients — the list goes on and on.

Add it all up and it is clear the rot runs very deep.

The reason for this is no mystery. The Gauteng health department has an annual budget of around R67 billion. This is more than 20% of the South African government’s entire spending on health. For the corrupt, the Gauteng health department is an obvious target.

And that it has been systematically targeted is not in doubt. Human rights activist Mark Heywood and Wits University Professor Alex van den Heever reckon that close to R20 billion has been stolen from the Gauteng health department over the past decade. “The scale of this theft makes former President Jacob Zuma look like a clumsy shoplifter,” Heywood writes in the Daily Maverick.

Perhaps the clearest dissection of how deep the rot goes is to be found in investigative journalist Jeff Wicks’ excellent book The Shadow State: Why Babita Deokaran Had to Die. In it, he unpacks the industrial-scale corruption at Tembisa Hospital where R830 million was siphoned off in just four months by a network of ruthless, well-connected looters. Allegedly, one of the key beneficiaries was Vusimusi “Cat” Matlala, a businessman with a criminal record and close ties not only to ANC bigwigs but also to senior police officials.

Meanwhile, the department is also failing to pay its creditors on time. Recently, City Press reported that Gauteng’s health department was the only provincial department flagged for noncompliance across all audit areas — despite having received a clean audit opinion. Accruals now exceed R8 billion, consuming 12% of the department’s R67 billion budget. “The problems are huge,” admitted Lebogang Maile, Gauteng’s MEC for Treasury and Economic Development.

Whichever way you slice it, the harsh truth is that even in 2025, the devastating crisis in Gauteng’s health system shows no sign of improvement. Corruption still plagues the department just as severely as it did a decade ago, if not more so. In the end, it is the province’s many committed healthcare workers and the people who depend on the public healthcare system who pay the price – whether a cancer patient or someone with a stoma and in need of a reliable supply of colostomy bags.

Where to from here?

Ultimately, the person responsible for fixing all this is Gauteng Premier Panyaza Lesufi. As Premier, he appoints both the province’s MEC for health and the head of its health department. It is because of Lesufi that Nkomo-Ralehoko and head of department Lesiba Malotana are still in place, despite the havoc around them.

From one perspective, it is hard to fathom why an ambitious politician like Lesufi would stand for such gross incompetence. His party, the ANC, has after all already been severely punished at the polls – in 2024 they got just under 35% of the votes in the province. Letting the province’s already eroded health services decay further can only lead to further electoral decline.

It is of course also possible that Lesufi and those around him are being misled, or intentionally not paying much attention, to just how bad things really are. Zuma too insisted that “we have a good story to tell” even as the state capture looters were in full stride. Maybe reality will similarly catch up with Lesufi if he continues faffing about while Rome burns.

After all, the courts have spoken. The health ombud has issued devastating reports. The Auditor-General has again put damning evidence on the table. Civil society has protested time and time again and spoken out in the media. Doctors and nurses have tried to raise issues through the correct channels and have been ignored. Expert help has been offered and declined. Most damningly, whistleblowers have paid with their lives.

Disclosure: SECTION27 is involved in the cancer court case proceedings as well as ongoing efforts seeking justice for the Life Esidimeni tragedy. Spotlight is published by SECTION27, but is editorially independent – an independence that the editors guard jealously. Spotlight is a member of the South African Press Council.

Republished from Spotlight under a Creative Commons licence.

Read the original article.