Why Tumours so Often Metastasise to the Spine

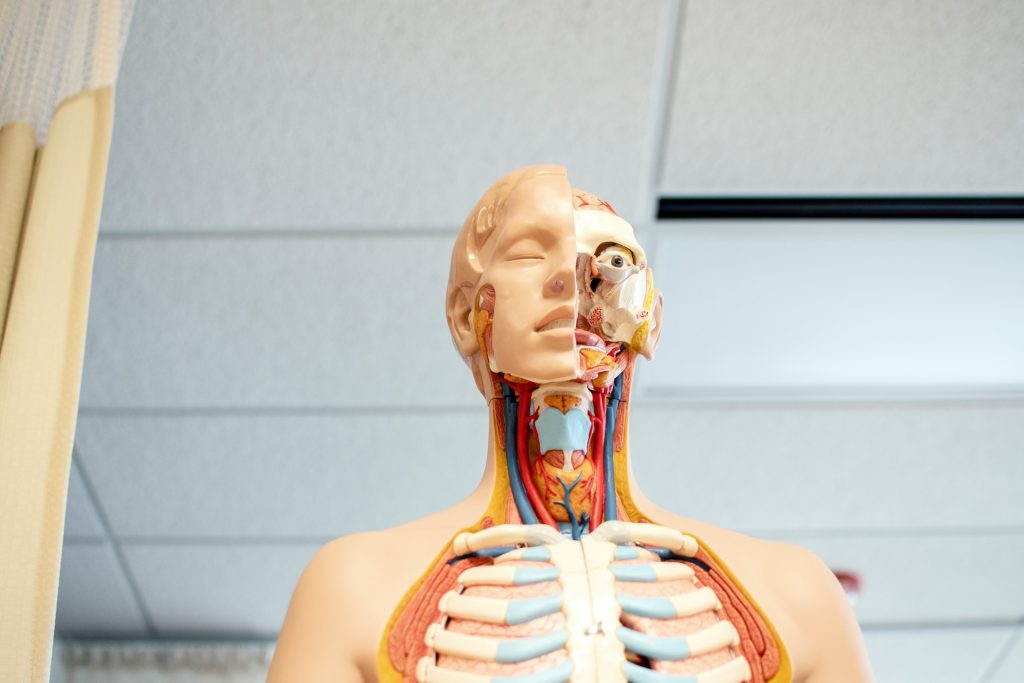

The vertebral bones that constitute the spine are derived from a distinct type of stem cell that secretes a protein favouring tumour metastases, according to a study led by researchers at Weill Cornell Medicine. The discovery, published in Nature, opens up a new line of research on spinal disorders and helps explain why solid tumours so often spread to the spine, and could lead to new orthopaedic and cancer treatments.

Vertebral bone was found to be derived from a stem cell that is different from other bone-making stem cells. Using bone-like “organoids” made from vertebral stem cells, they showed that the known tendency of tumours to spread to the spine rather than long bones is due largely to a protein called MFGE8, secreted by these stem cells.

“We suspect that many bone diseases preferentially involving the spine are attributable to the distinct properties of vertebral bone stem cells,” said study senior author Dr Matthew Greenblatt.

In recent years, Dr Greenblatt and other scientists have found that different types of bone are derived from different types of bone stem cells. Since vertebrae develop along a different pathway early in life, and also appear to have had a distinct evolutionary trajectory, Dr Greenblatt and his team hypothesised that a distinct vertebral stem cell probably exists.

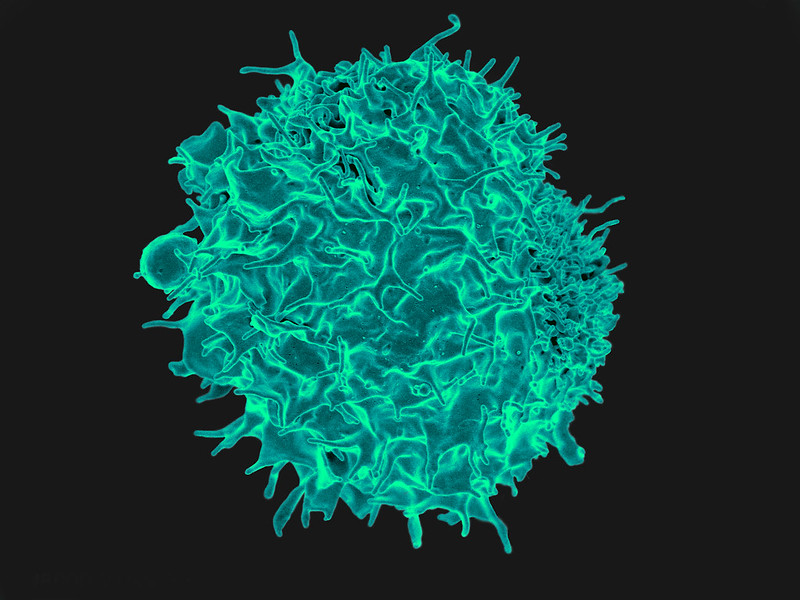

The researchers started out by isolating what are broadly known as skeletal stem cells, which give rise to all bone and cartilage, from different bones in lab mice based on known surface protein markers of such cells. They then analysed gene activity in these cells to see if they could find a distinct pattern for the ones associated with vertebral bone.

This effort yielded two key findings. The first was a new and more accurate surface-marker-based definition of skeletal stem cells as a whole. This new definition excluded a set of cells that are not stem cells that had been included in the old stem cell definition, thus clouding some prior research in this area.

The second finding was that skeletal stem cells from different bones do indeed vary systematically in their gene activity. From this analysis, the team identified a distinct set of markers for vertebral stem cells, and confirmed these cells’ functional roles to form spinal bone in further experiments in mice and in lab-dish cell culture systems.

The researchers next investigated the phenomenon of the spine’s relative attraction for tumour metastases, including breast, prostate and lung tumours, compared to other types of bone. The traditional theory, dating to the 1940s, is that this “spinal tropism” relates to patterns of blood flow that preferentially convey metastases to the spine versus long bones. But when the researchers reproduced the spinal tropism phenomenon in animal models, they found evidence that blood flow isn’t the explanation, finding instead a clue pointing to vertebral stem cells as the possible culprits.

“We observed that the site of initial seeding of metastatic tumour cells was predominantly in an area of marrow where vertebral stem cells and their progeny cells would be located,” said study first author Dr Jun Sun, a postdoctoral researcher in the Greenblatt laboratory.

Subsequently, the team found that removing vertebral stem cells eliminated the difference in metastasis rates between spine bones and long bones. Ultimately, they determined that MFGE8, a protein secreted in higher amounts by vertebral compared to long bone stem cells, is a major contributor to spinal tropism. To confirm the relevance of the findings in humans, the team collaborated with investigators at Hospital for Special Surgery to identify the human counterparts of the mouse vertebral stem cells and characterise their properties.

The researchers are now exploring methods for blocking MFGE8 to reduce the risk of spinal metastasis in cancer patients. More generally, said Dr Greenblatt, they are studying how the distinctive properties of vertebral stem cells contribute to spinal disorders.

“There’s a subdiscipline in orthopaedics called spinal orthopaedics, and we think that most of the conditions in that clinical category have to do with this stem cell we’ve just identified,” Dr Greenblatt said.

Source: Weill Cornell Medicine