Considering Sex Hormones Led to Better Identification of Genes Linked to Type 2 Diabetes

Genomic and hormone study of white Europeans finds 22 additional disease-related variants

Researchers identified almost two dozen previously unknown genetic variants linked to type 2 diabetes by including participants’ hormone levels in their analysis. Yan V. Sun of Emory University, USA, and colleagues reports these findings in the open-access journal PLOS Genetics.

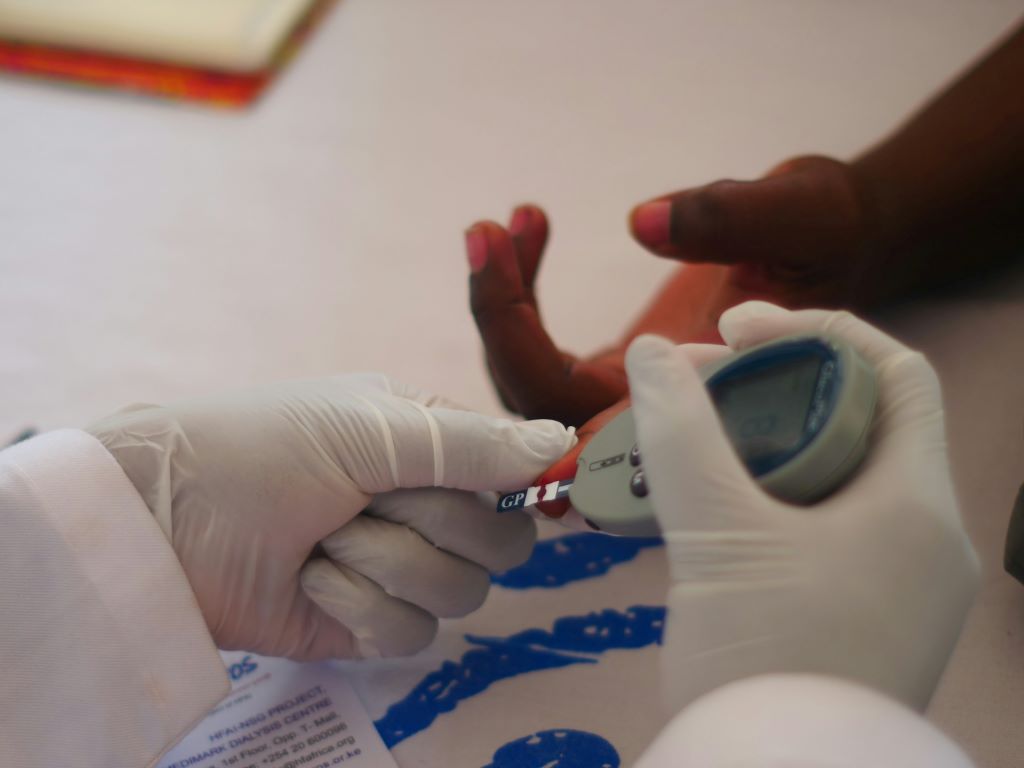

Type 2 diabetes affects an increasing number of people worldwide, and more often affects men than women. The disease is caused by a mix of genetic and lifestyle factors, but little is known about how someone’s environment – both inside and outside the body – interacts with their genes to impact a person’s risk of developing the disease.

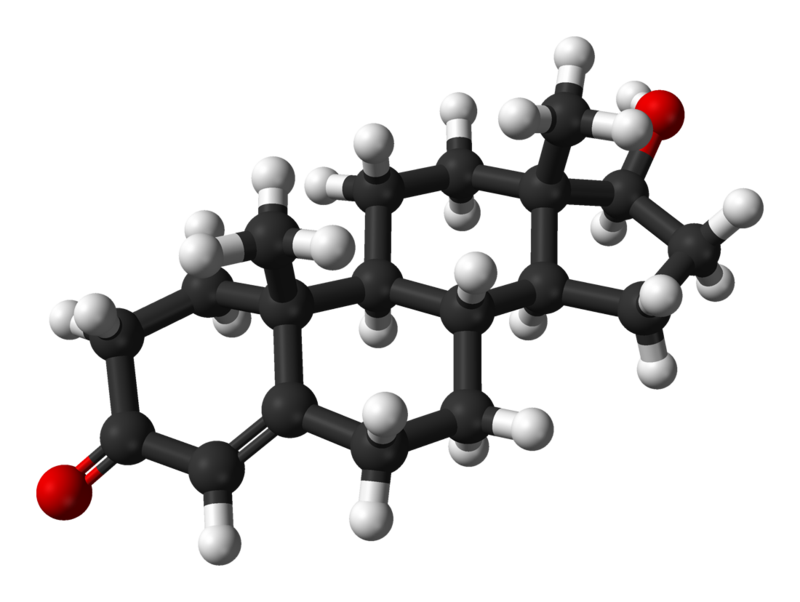

In the new study, researchers performed genome-wide interaction studies to investigate whether a person’s hormone levels interact with their genetic variants to affect their risk of developing type 2 diabetes. They grouped males and females independently and considered measurements of three types of sex hormones – total testosterone, bioavailable testosterone and sex-hormone binding globulin. The information came from white European participants in the UK Biobank, which contains biological samples and health data from half a million people.

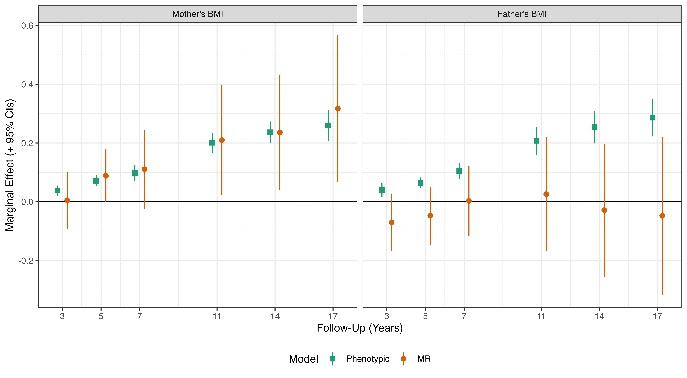

The researchers used statistical analyses to identify relevant variants in the genomes of individuals with and without type 2 diabetes. By taking into account hormone levels, the analysis was able to identify 22 spots on the genome that increased a person’s risk for type 2 diabetes. These variants had not been reported previously in the most recent genomic study for type 2 diabetes.

The new study suggests that a person’s hormone levels may be interacting with their genes to increase their odds of having type 2 diabetes. For future studies, the researchers recommended that additional hormone measurements for each participant and more diverse cohorts should be included. They conclude that this approach, which includes environmental factors in genomic studies, may help us to identify additional disease-related genes and gain a better understanding of the mechanisms behind complex diseases.

The authors add, “We found that sex hormone levels contribute to differences in genetic risk factors for type 2 diabetes in men and women. By analyzing data for men and women separately, we identified new genetic associations with type 2 diabetes.”

The lead analyst, Amonae Dabbs-Brown notes, “I actually used to work at the CDC developing methods to measure some of these sex hormones. It’s really exciting to see what happens downstream. Maybe one day I’ll even get to see how these analyses are used in the clinic!”

Provided by PLOS

In your coverage, please use this URL to provide access to the freely available paper in PLOS Genetics: https://plos.io/3ViXDKH

Contact: Rob Spahr [rob.spahr@emory.edu]

Citation: Dabbs-Brown A, Liu C, Hui Q, Wilson PW, Zhou JJ, Gwinn M, et al. (2025) Identification of gene-sex hormone interactions associated with type 2 diabetes among men and women. PLoS Genet 21(9): e1011470. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgen.1011470

Author countries: United States

Funding: This work is supported in part by funding from the National Institutes of Health (HL154996 to YVS, DK139632 to YVS, and HL156991 to YVS). The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript. YVS received salary support from the National Institutes of Health.

Competing interests: The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.