Oxford Researchers Develop Uniquely Shaped Microstent to Combat Glaucoma

A team of researchers at the University of Oxford have unveiled a pioneering ‘microstent’ which could revolutionise treatment for glaucoma, a common but debilitating condition. The study has been published in The Innovation, Cell Press.

Glaucoma is a leading cause of vision loss, second only to cataracts. Globally, 7.7 million people were blind or visually impaired due to glaucoma in 2020. The condition can cause irreversible damage to the optic nerve, due to increased pressure within the eyeball. Current treatment options – principally surgery to create openings in the eye or insert tubes to drain fluid – are highly invasive, carry risk of complications, and have limited durability.

‘Our deployable microstent represents a significant advancement in glaucoma treatment,’ said lead author Dr Yunlan Zhang (University of Oxford at the time of the study/University of Texas). ‘Current surgical implants for this type of glaucoma have been shown to have limited long-term effectiveness, being susceptible to failure due to fibrosis (scarring) in the eye.’

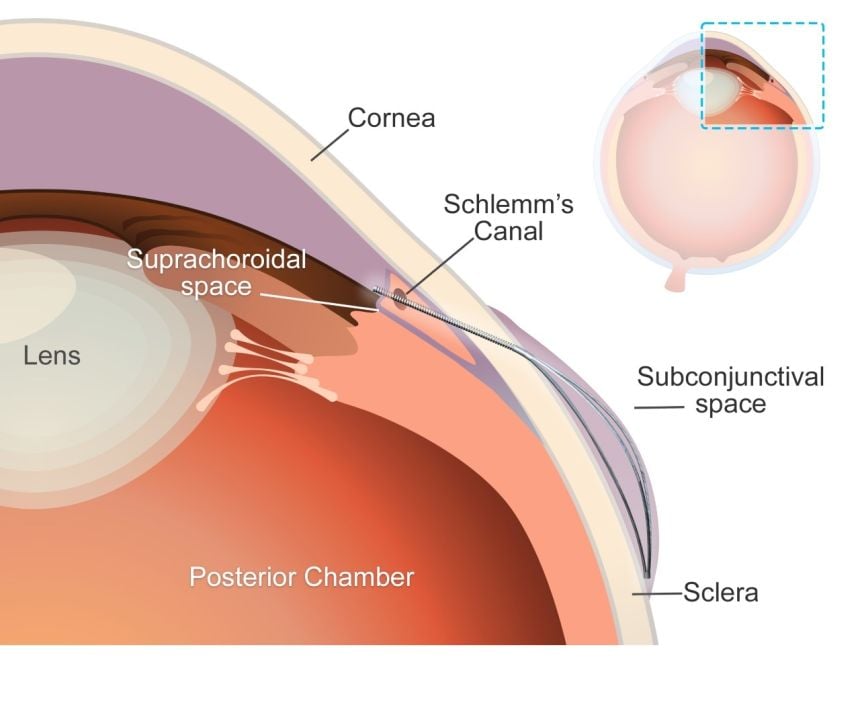

The new microstent features a unique structural shape that allows it to expand once in the eye. At 200µm, less than a quarter of a millimetre, the stent’s tiny diameter enables it to fit within the needle of a standard hypodermic syringe, for minimally-invasive insertion. Once in place and expanded, the microstent spans the fluid-filled space between the white of the eye and the membrane that covers it.

By supporting this space, the stent reduces the excessive fluid buildup and resulting intraocular pressure in the eye which is responsible for the most common type of glaucoma, primary open-angle glaucoma. Initial trials carried out in rabbits found that the microstents lowered eye pressure in less than a month with minimal inflammation and scarring. Furthermore, the microstent achieved a greater reduction of eye pressure than a standard tubular implant.

This development has the potential to transform the landscape of glaucoma therapy. By offering an enhanced solution in the minimally invasive glaucoma surgery field that combines mechanical innovation with biocompatibility, we hope to improve patient outcomes and quality of life.

Senior co-author Dr Jared Ching (Department of Engineering Science, University of Oxford).

Senior co-author, Professor Zhong You (Department of Engineering Science, University of Oxford) said: ‘Our microstent is made from a durable and super-flexible nickel-titanium alloy called nitinol, renowned for its proven long-term safety for ocular use. Its unique material and structural properties help prevent subsequent movement, improve durability, and ensure long-term efficacy.’

The research team used advanced modelling techniques to guide the microstent’s design and ensure compatibility with the anatomy of the eye. The device’s superelastic properties enable it to accommodate how the eye changes and stretches over time without permanent deformation, enhancing its durability and functionality.

Over half a million people in the UK have glaucoma – 2% of everyone over the age of 40 – and it is one of the most common causes of blindness worldwide. The introduction of this microstent could mark a pivotal step in enhancing treatment efficacy and accessibility.

The study ‘A Novel Deployable Microstent for the Treatment of Glaucoma has been published in The Innovation, Cell Press.

Source: Oxford University