Cinnamon Could Affect Drug Metabolism in the Body

Cinnamon is one of the oldest and most commonly used spices in the world – but a new study from the University of Mississippi indicates a compound in it could interfere with some prescription medications.

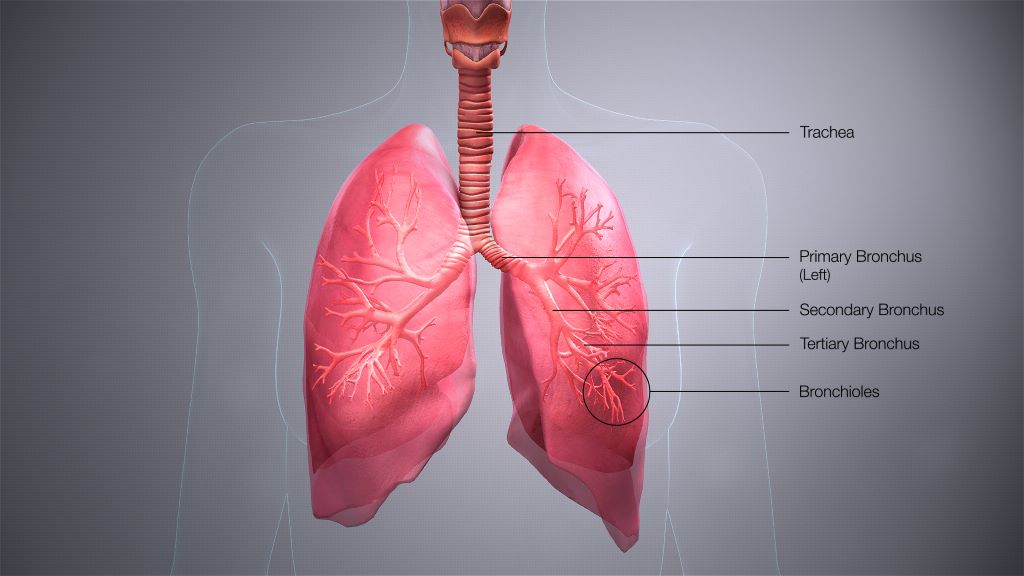

In a recent study published in Food Chemistry: Molecular Sciences, the researchers found that cinnamaldehyde, a primary component of cinnamon, activates receptors that control the metabolic clearance of medication from the body, meaning consuming large amounts of cinnamon could reduce the effects of drugs.

“Health concerns could arise if excessive amounts of supplements are consumed without the knowledge of health care provider or prescriber of the medications,” said Shabana Khan, a principal scientist in the natural products centre. “Overconsumption of supplements could lead to a rapid clearance of the prescription medicine from the body, and that could result in making the medicine less effective.”

Aside from its culinary uses, cinnamon has a long history of being used in traditional medicine and can help manage blood sugar and heart health and reduce inflammation. But how the product actually functions in the body remains unclear.

Sprinkling cinnamon on your morning coffee is unlikely to cause an issue, but using highly concentrated cinnamon as a dietary supplement might.

“Despite its vast uses, very few reports were available to describe the fate of its major component – cinnamaldehyde,” Khan said. “Understanding its bioaccessibility, metabolism and interaction with xenobiotic receptors was important to evaluate how excess intake of cinnamon would affect the prescription drugs if taken at the same time.”

Not all cinnamon is equal. Cinnamon oil – which is commonly used topically as an antifungal or antibacterial and as a flavouring agent in food and drinks – presents almost no risk of herb-drug interactions, said Amar Chittiboyina, the center’s associate director.

But cinnamon bark – especially Cassia cinnamon, a cheaper variety of cinnamon that originates in southern China – contains high levels of coumarin, a blood thinner, compared to other cinnamon varieties. Ground Cassia cinnamon bark is what is normally found in grocery stores.

“In contrast, true cinnamon from Sri Lanka carries a lower risk due to its reduced coumarin content,” he said. “Coumarin’s anticoagulant properties can be hazardous for individuals on blood thinners.”

More research is needed to fully understand the role that cinnamon plays in the body and what potential herb-drug interactions may occur, said Bill Gurley, a principal scientist in the Ole Miss center and co-author of the study.

“We know there’s a potential for cinnamaldehyde to activate these receptors that can pose a risk for drug interactions,” he said. “That’s what could happen, but we won’t know exactly what will happen until we do a clinical study.”

Until those studies are complete, the researchers recommend anyone interested in using cinnamon as a dietary supplement to check with their doctor first.

“People who suffer from chronic diseases – like hypertension, diabetes, cancer, arthritis, asthma, obesity, HIV, AIDS or depression – should be cautious when using cinnamon or any other supplements,” Khan said. “Our best advice is to talk to a health care provider before using any supplements along with the prescription medicine.

“By definition, supplements are not meant to treat, cure or mitigate any disease.”

Source: University of Mississippi