New Research Points to Clot Lysis Protein for Cholesterol Control

While high levels of low-density lipoprotein (LDL) can be reduced by drugs such as statins, reducing the risk of myocardial infarction and stroke, risk still remains in the form of other cholesterols. New research published in the journal Science describes how manipulating a protein involved in blood clot lysis could help bring cholesterol levels even more under control.

Heart disease remains a leading cause of death worldwide, despite advances in cholesterol-lowering medication such as proprotein convertase subtilisin-kexin type 9 inhibitors, which were approved by the FDA in 2015. One clinical trial following patients taking proprotein convertase subtilisin-kexin type 9 inhibitors demonstrated a benefit while also revealing an opportunity for improvement as the absolute risk reduction was considered modest at 1.5%.

“It is clear that there is more going on than just what statins and these newer inhibitor drugs can control,” says Ze Zheng, MBBS, PhD, MCW assistant professor of medicine. “More therapies are needed, and to get them we need to know more about other sources of risk for heart disease, especially heart attacks and strokes.”

So-called “bad cholesterol” is carried by apolipoprotein B (apoB) which forms well-structured particles with lipids and proteins. These particles serve as stable vehicles for transporting lipids such as cholesterol in the bloodstream. These lipid-rich particles mostly include very-low-density lipoprotein (VLDL) and low-density lipoprotein (LDL). Current cholesterol-lowering reduce mainly LDL levels, which though important to control, is not the only risk factor for heart disease. In fact, the other lipoproteins in the same group as LDL are not reduced by much with available treatments. Dr Zheng and her team are investigating how to reduce levels of other members of this family of lipoproteins, especially VLDL.

“With my background in lipid metabolism, I found myself consistently checking lipid levels even during studies regarding blood clot lysis and how an impairment in the body’s ability to remove blood clots affects the risk of blood vessel blockages,” Dr Zheng adds. “I was just naturally curious about it, and I noticed that a protein I was studying may have an effect on the amount of circulating cholesterol.”

In prior research, Dr Zheng has helped define a new cellular source of this protein, tissue-type plasminogen activator (tPA), and its role in breaking down blood clots and preventing blood vessel blockages. To understand its potential influence on cholesterol levels, her team used a gene-editing technique to stop liver cells from producing tPA in mice prone to blood vessel plaque formation. The scientists found that the mice developed increased lipoprotein-cholesterol in this experiment, and then validated the findings in follow-up studies using human liver cells and a type of rat liver cell known to produce VLDL in a way similar to human liver cells. With these and other experimental results, Dr Zheng and her team have demonstrated a new, important role that liver tPA influences blood cholesterol levels while underscoring a meaningful connection between the liver, heart and blood vessels.

“After defining this new role for tPA, we turned our attention to the question of how it changes blood cholesterol levels,” notes Wen Dai, MD, research scientist, Versiti Blood Research Institute.

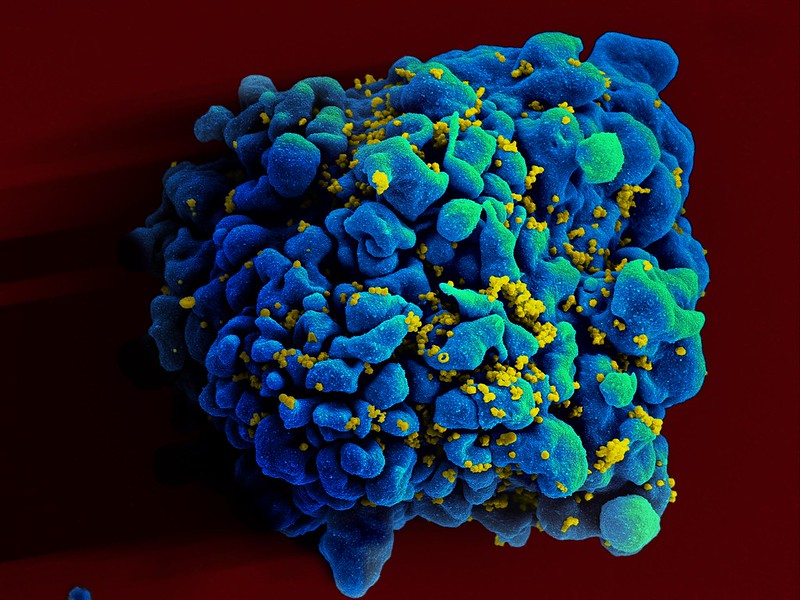

The liver contributes to the majority of the “bad” apoB-lipoproteins by making VLDL. The team focused on whether and how tPA impacts the process of VLDL assembly in the liver. Microsomal triglyceride transfer protein (MTP) is required for the assembly of VLDL due to its role carrying lipids to the apoB. The scientists determined that tPA binds with the apoB protein in the same place as MTP. The more tPA is present, the fewer opportunities MTP has to connect with apoB and catalyse the creation of new VLDL. Essentially, MTP tries to pass a cholesterol to apoB, but tPA interferes with this pocess.

“Based on our prior research, we knew it also was critical to look at tPA’s primary inhibitor,” Dr. Zheng says.

Plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 (PAI-1) is known to block the activity of tPA. Scientists also have found a correlation between PAI-1 levels in blood and the development of disease due to plaque formation and blockages in blood vessels. The team found that higher levels of PAI-1 reduced the ability of tPA to bind with apoB proteins, rendering tPA less effective at competing with MTP to prevent VLDL production. Returning to the biological gridiron, PAI-1 might be a decoy receiver that distracts tPA until MTP connects with apoB for a big gain. The team studied this interaction in human subjects with a naturally occurring mutation in the gene carrying the code for PAI-1. The researchers found that these individuals, as predicted, had higher tPA levels and lower LDL and VLDL levels than individuals from the same community who did not have the same mutation.

“We are investigating therapeutic strategies based on these findings regarding tPA, MTP and PAI-1,” Dr Zheng notes. “I think we may be able to reduce the residual cardiovascular risk that has persisted even as treatment has advanced.”

Source: Medical College of Wisconsin