Bubonic Plague Treatment Proven Highly Effective and Safe in Global First

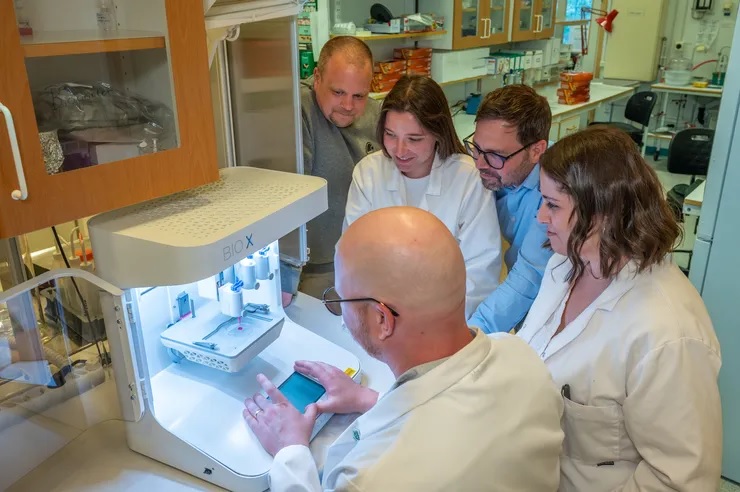

Researchers from the UK and Madagascar, in collaboration with Madagascar’s health services and national plague programme, have conducted the world’s first rigorous clinical trial of treatments for bubonic plague.

The IMASOY trial provides the first robust evidence of the efficacy and safety of two treatment regimens. They also found that a ten-day course of an oral antibiotic (ciprofloxacin) is a highly effective and safe alternative to existing treatment with injectable antibiotic requiring hospitalisation.

Plague has scourged humanity for millennia. Though cases have been declining, it remains a high-threat pathogen of pandemic potential, due to its widespread animal reservoir and potential for being weaponised via deliberate release. Most continents see sporadic cases of bubonic plague every year, with Madagascar reporting approximately 80% of global cases. Bubonic plague is a life-threatening disease with mortality ranging from 15-25%.

The results from the trial, published in the New England Journal of Medicine, are the outcome of a hugely ambitious clinical trial conducted over the last five years in rural Madagascar.

With many cases occurring in remote villages and with outbreaks being unpredictable, the team deployed dozens of research assistants, and trained over 230 local doctors and nurses and 1300 village health workers. The trial was embedded within Madagascar’s national health service and was conducted with the support of the Ministry of Public Health.

Several treatment options are included in the current international and national guidelines, but none of them have been rigorously tested in humans. Regulatory approval has been based solely on data from animal studies and human safety data.

Researchers designed the IMASOY trial to test two treatments for plague. Patients were randomly allocated to receive either a ten-day oral regimen of ciprofloxacin (an antibiotic tablet which can be taken at home), or a regimen requiring three days’ injectable gentamicin followed by seven days’ ciprofloxacin, (with the intravenous (IV) therapy requiring patients to be hospitalised).

450 patients with clinically suspected bubonic plague were enrolled between 2020-2024 at 47 sites in 11 districts in Madagascar and treated with either regimen. Of these, 222 plague infections were confirmed by laboratory testing.

Key findings:

• Both regimens were found to be highly effective and safe, with overall treatment success rates of about 90% and an overall mortality rate of about 4%.

• A ten-day ciprofloxacin regimen has many advantages over a regimen requiring three days of injectable antibiotics. It alleviates bed space (particularly in health centres with minimal bed availability for the surrounding villages), reduces healthcare worker workload, and is much cheaper – costing about one-tenth of the current treatment regimen, depending on the route of administration.

With funding from Wellcome and the UK Foreign, Commonwealth, and Development Office, researchers from the University of Oxford, Institut Pasteur de Madagascar, Centre Hospitalier Universitaire Joseph Raseta Befelatanana, Centre d’Infectiologie Charles Mérieux, London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, along with Madagascar’s health services and national plague programme, collaborated through the International Severe Acute Respiratory and emerging Infection Consortium (ISARIC) to fill this gap in knowledge.

Piero Olliaro, Professor at the Pandemic Science Institute, University of Oxford and senior author of the study said: ‘Despite its deadly history, we’ve had little clinical evidence on treating bubonic plague – until now. Thanks to the patients and healthcare workers in the trial, we now have real-world proof of effective, safe treatment. Ongoing data analysis will deepen our understanding of the disease, including risk factors, symptoms, and diagnostics.’

Mihaja Raberahona, physician at CHU Joseph Raseta Befelatanana and researcher at the Centre d’Infectiologie Charles Mérieux Madagascar said: ‘In Madagascar, where plague cases occur in remote rural locations with limited healthcare infrastructure, taking a straightforward oral antibiotic is vastly preferable to a treatment requiring injections. It alleviates healthcare worker workload and is also much cheaper – costing about one-tenth of the current treatment regimen.’

Rindra Vatosoa Randremanana, Medical epidemiologist at Institut Pasteur de Madagascar said: ‘The trial was a massive operational undertaking. Many patients were in remote villages and the unpredictable nature of the outbreaks made the research very challenging. Recruiting the 450 patients, of whom about half were confirmed with bubonic plague, took five plague transmission seasons and an army of research assistants, doctors and community health workers. We are hugely grateful to everyone who took part.’

The impact of this study is far-reaching. As a result of the trial, the researchers will be working with national and international bodies like the World Health Organization (WHO) to provide the evidence that may be required to update clinical guidelines, thereby translating the results into practice and saving lives.

The full paper, ‘Ciprofloxacin versus Aminoglycoside-Ciprofloxacin for Bubonic Plague‘, is published in the New England Journal of Medicine.

Source: University of Oxford