Mortality Risk is Six Times Higher in Hospital Patients with Dyspnoea

The risk of dying is six times higher among patients who become short of breath after being admitted to hospital, according to research published on Monday in ERJ Open Research. Patients who were in pain were not more likely to die.

The study of nearly 10 000 people suggests that asking patients if they are feeling short of breath could help doctors and nurses to focus care on those who need it most.

The study is the first of its kind and was led by Associate Professor Robert Banzett from Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Harvard Medical School, Boston, USA. He said: “In hospital, nurses routinely ask patients to rate any pain they are experiencing, but this is not the case for dyspnoea. In the past, our research has shown that most people are good at judging and reporting this symptom, yet there is very little evidence on whether it’s linked to how ill hospital patients are.”

Working with nurses at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, who documented patient-reported dyspnoea twice per day, the researchers found that it was feasible to ask hospital patients to rate their dyspnoea from 0 to 10, in the same way they are asked to rate their pain. Asking the question and recording the answer only took 45 seconds per patient.

Researchers analysed patient-rated shortness of breath and pain for 9 785 adults admitted to the hospital between March 2014 and September 2016. They compared this with data on outcomes, including deaths, in the following two years.

This showed that patients who developed shortness of breath in hospital were six times more likely to die in hospital than patients who were not feeling short of breath. The higher patients rated their shortness of breath the higher their risk of dying. Patients with dyspnoea were also more likely to need care from a rapid response team and to be transferred to intensive care.

Twenty-five per cent of patients who were feeling short of breath at rest when they were discharged from hospital died within six months, compared to seven per cent mortality among those who felt no dyspnoea during their time in hospital.

Conversely, researchers found no clear link between pain and risk of dying.

Professor Banzett said: “It is important to note that dyspnoea is not a death sentence – even in the highest risk groups, 94% of patients survive hospitalisation, and 70% survive at least two years following hospitalisation. But knowing which patients are at risk with a simple, fast, and inexpensive assessment should allow better individualised care. We believe that routinely asking patients to rate their shortness of breath will lead to better management of this often-frightening symptom.

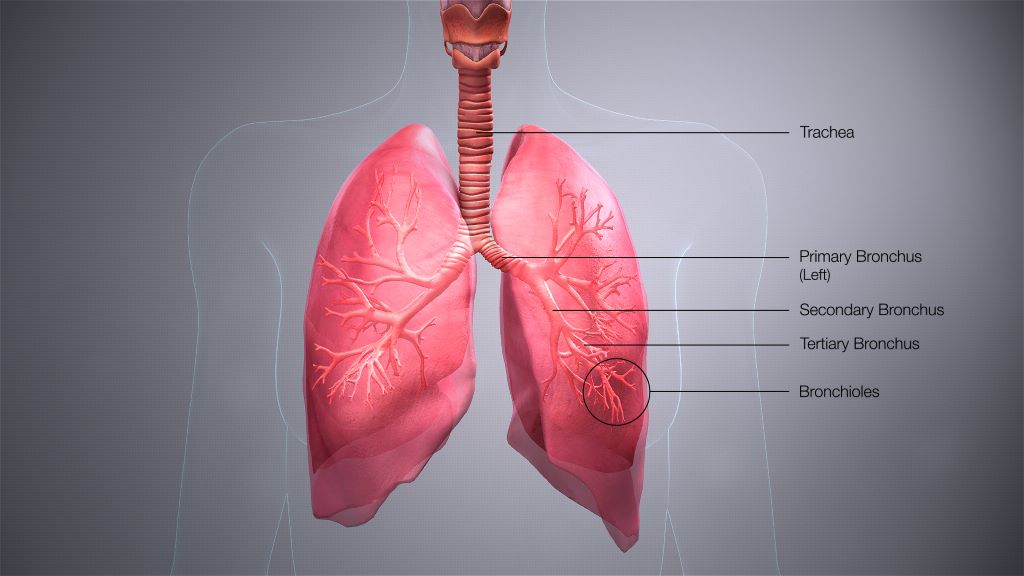

“The sensation of dyspnoea is an alert that the body is not getting enough oxygen in and carbon dioxide out. Failure of this system is an existential threat. Sensors throughout the body, in the lungs, heart and other tissues, have evolved to report on the status of the system at all times, and provide early warning of impending failure accompanied by a strong emotional response.

“Pain is also a useful warning system, but it does not usually warn of an existential threat. If you hit your thumb with a hammer, you will probably rate your pain 11 on a scale of 0-10, but there is no threat to your life. It is possible that specific kinds of pain, for instance pain in internal organs, may predict mortality, but this distinction is not made in the clinical record of pain ratings.”

The researchers say their findings should be confirmed in other types of hospital elsewhere in the world, and that research is needed to show whether asking patients to rate their shortness of breath leads to better treatments and outcomes.

Professor Hilary Pinnock is Chair of the European Respiratory Society’s Education Council, based at the University of Edinburgh and was not involved in the research. She said: “Historically, the monitoring of vital signs in hospitalised patients includes respiratory rate along with temperature and pulse rate. In a digital age, some have questioned the value of this workforce-intensive routine, so it is interesting to read about the association of subjective breathlessness with mortality and other adverse outcomes.

“Breathlessness was assessed on a 0-10 scale which took less than a minute to administer. These noteworthy findings should trigger more research to understand the mechanisms underpinning this association and how this ‘powerful alarm’ can be harnessed to improve patient care.”

Source: EurekAlert!