First Evidence of a ‘Nearly Universal’ Pharmacological Chaperone for Rare Disease

Study hints at a “one-drug-per-protein” rather than “one-drug-per-mutation” strategy

A study published in Nature Structural & Molecular Biology is the first time researchers have shown evidence that a single drug, already licensed for medical use, can stabilise nearly all mutated versions of a human protein, regardless of where the mutation is in the sequence.

The researchers engineered seven thousand versions of the vasopressin V2 receptor (V2R), which is critical for normal kidney function, creating all possible mutated variants in the lab. Faulty mutations in V2R prevent kidney cells from responding to the hormone vasopressin, leading to the inability to concentrate urine and resulting in excessive thirst and large volumes of dilute urine, causing nephrogenic diabetes insipidus (NDI), also known as arginine vasopressin resistance, a rare disease affecting roughly one in 25 000 people.

When they carried out further experiments looking specifically at mutations observed in patients, they found that the oral medicine tolvaptan, clinically-approved for other kidney conditions, restored receptor levels to near-normal for 87 per cent of destabilised mutations (60 out of 69 known disease-causing mutations, and 835 out of 965 predicted disease-causing mutations).

“Inside the cell, V2R travels through a tightly managed traffic system. Mutations cause a jam, so V2R never reaches the surface. Tolvaptan steadies the receptor for long enough to allow the cell’s quality control system to wave it through,” explains Dr. Taylor Mighell, first author of the study and postdoctoral researcher at the Centre for Genomic Regulation (CRG) in Barcelona.

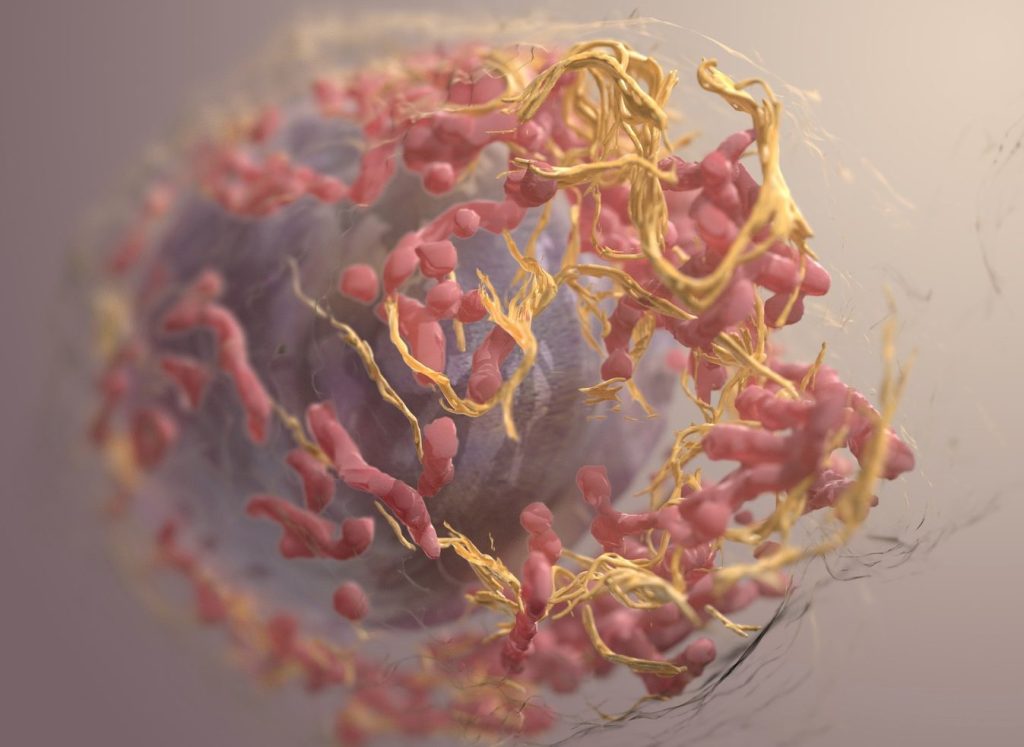

The research group have previously shown that most mutations affect a protein’s function by altering its stability, making the whole structure wobblier than normal. According to the authors of the study, tolvaptan works regardless of where the mutation is because proteins switch between folded and unfolded forms. Most V2R mutations make the unfolded form more likely. When tolvaptan binds to V2R, it favours the folded form over the unfolded one.

The research is the first proof-of-principle study to demonstrate that a drug can act like a “nearly universal” pharmacological chaperone, meaning it can latch onto a protein and stabilise the structure regardless of where it’s mutated, in this case, in nearly nine out of ten cases.

The findings could help tackle a longstanding challenge in rare disease medicine. A rare disease is any disease affecting fewer than 1 in 2000 people. Though individual prevalence is low, rare diseases are a formidable challenge for global health because there are thousands of different types, meaning around 300 million people worldwide live with a rare condition.

Most rare diseases are caused by mutations in DNA. The same gene can be mutated in many ways, so patients with “the same” rare disease can have different mutations driving the condition. Because few individuals will have the same mutation, drug development is slow and commercially unattractive. Most treatments help manage symptoms rather than tackling the root cause of a rare disease.

Previous studies show that between 40 and 60% of rare-disease causing mutations affect a protein’s stability. If future studies confirm the rescued receptors work normally, the study offers a new roadmap for rare-disease drug development. Rather than look for a drug that targets a single mutation, researchers could instead look for one that targets stabilising an entire protein.

V2R is part of the human body’s largest family of receptors, also known as G-protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs). These roughly 800 genes are the targets of about a third of all approved drugs. Many rare and common diseases arise when GPCRs don’t fold or traffic correctly to the cell surface, even though their signalling parts are largely intact.

“If the behaviour we found holds for others members of GPCR family, drug developers could swap spending years of hunting for bespoke therapeutic molecules and try looking for general or universal pharmacological chaperones instead, greatly accelerating the drug development pipeline for many genetic diseases,” concludes ICREA Research Professor Ben Lehner, Group Leader at the Wellcome Sanger Institute (Hinxton, UK) and Centre for Genomic Regulation (Barcelona).

Source: EurekAlert!