Can African Countries Meet 2030 Childhood Immunisation Goals?

Researchers analysed 1 million records from national health surveys in 38 African countries and found progress in childhood immunisation coverage – but many countries, including South Africa, may still fall short of global targets

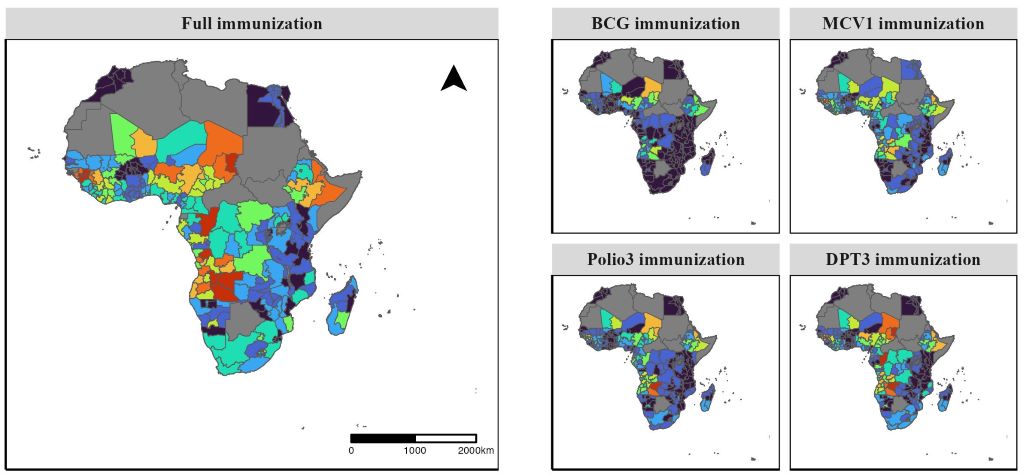

Image credit: Nguyen PT et al., 2025, PLOS Medicine, CC-BY 4.0

In the last two decades, childhood immunisation coverage improved significantly across most African countries. However, at least 12 countries, including South Africa, are unlikely to achieve global targets for full immunisation by 2030, according to a new study published July 29th in the open-access journal PLOS Medicine by Phuong The Nguyen of Hitotsubashi University, Japan, and colleagues.

Vaccines are one of the most effective ways to protect children from deadly diseases, yet immunisation coverage is still suboptimal in many African countries. Monitoring and progress in childhood immunisations at the national and local level is essential for refining health programmes and achieving global targets in these countries.

In the new study, researchers used childhood immunisation data contained in approximately 1 million records from 104 nationally representative Demographic and Health Surveys (DHS) conducted in 38 African countries between 2000 and 2019. Using modelling techniques, they estimated immunisation coverage trends through 2030 and assessed disparities across geographic regions and between socioeconomic groups.

The data showed overall improvements in immunisation coverage between 2000 and 2019. It forecast that, if current trends continue, most countries are projected to meet or exceed targets for achieving 80% or 90% coverage of vaccines against tuberculosis, measles, polio, diphtheria, pertussis (whooping cough), and tetanus. However, 12 of 38 countries are not on track to meet full immunisation goals, including high-development nations like South Africa, Egypt, and Congo Brazzaville. The study also pinpointed significant socioeconomic inequalities in coverage, with gaps in coverage of up to 58% between wealth quintiles. While these disparities were present across all countries, most are projected to shrink by 2030 –except in Nigeria and Angola, where inequalities are expected to persist or grow.

“These achievements are likely the result of sustained progress driven by decades of national and sub-national initiatives along with international support aimed at prioritising immunisation,” the authors say. “However, progress towards full immunisation coverage remains slow in 12 African countries examined. In most African nations, challenges related to vaccine affordability, accessibility, and availability remain major obstacles, driven by weak primary healthcare systems and limited resources.”

The authors add, “This study shows that while childhood immunisation coverage has improved in Africa, progress is uneven. Many countries and regions remain off track to meet global targets by 2030.”

The authors conclude, “Conducting this study reinforced how critical reliable sub-national data is for identifying communities being left behind. We hope the findings will help inform more equitable and targeted immunisation strategies.”

Provided by PLOS