Alzheimer’s Drug Lecanemab Well Tolerated in Real-world Use

Side effects of lecanemab are manageable, study finds

The Food and Drug Administration’s approval in 2023 of lecanemab – a novel Alzheimer’s therapy shown in clinical trials to modestly slow disease progression – was met with enthusiasm by many in the field as it represented the first medication of its kind able to influence the disease. But side effects of brain swelling and bleeding emerged during clinical trials that have left some patients and physicians hesitant about the treatment. [Especially considering its $26 500 per year cost – Ed.]

Medications can have somewhat different effects once they are released into the real world with broader demographics. Researchers at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis set out to study the adverse events associated with lecanemab treatment in their clinic patients and found that significant adverse events were rare and manageable.

Consistent with the results from carefully controlled clinical trials, researchers found that only 1% of patients experienced severe side effects that required hospitalisation. Patients in the earliest stage of Alzheimer’s with very mild symptoms experienced the lowest risk of complications, the researchers found, helping to inform patients and clinicians as they navigate discussions about the treatment’s risks.

The retrospective study, published in JAMA Neurology, focused on 234 patients with very mild or mild Alzheimer’s disease who received lecanemab infusions in the Memory Diagnostic Center at WashU Medicine, a clinic that specialises in treating patients with dementia.

“This new class of medications for early symptomatic Alzheimer’s is the only approved treatment that influences disease progression,” said Barbara Joy Snider, MD, PhD, a professor of neurology and co-senior author on the study. “But fear surrounding the drug’s potential side effects can lead to treatment delays. Our study shows that WashU Medicine’s outpatient clinic has the infrastructure and expertise to safely administer and care for patients on lecanemab, including the few who may experience severe side effects, leading the way for more clinics to safely administer the drug to patients.”

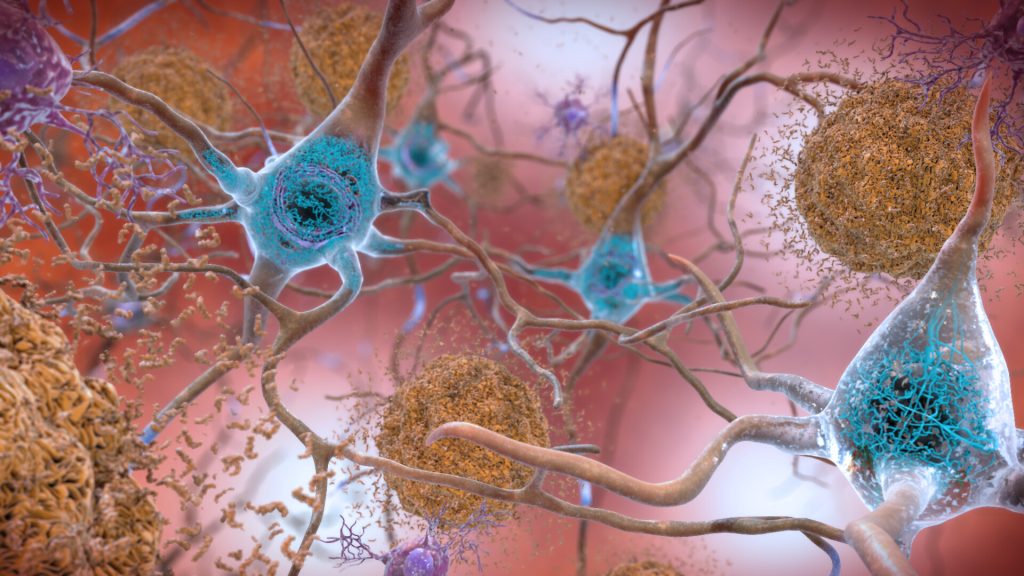

Lecanemab is an antibody therapy that clears amyloid plaque proteins, extending independent living by 10 months, according to a recent study led by WashU Medicine researchers. Because amyloid accumulation is the first step in the disease, doctors recommend the drug for people in the early stage of Alzheimer’s, with very mild or mild symptoms. The researchers found that only 1.8% of patients with very mild Alzheimer’s symptoms developed any adverse symptoms from treatment compared with 27% of patients with mild Alzheimer’s.

“Patients with the very mildest symptoms of Alzheimer’s will likely have the greatest benefit and the least risk of adverse events from treatment,” said Snider, who led clinical trials for lecanemab at WashU Medicine. “Hesitation and avoidance can lead patients to delay treatment, which in turn increase the risk of side effects. We hope the results help reframe the conversations between physicians and patients about the medication’s risks.”

Hesitation around lecanemab stems from a side effect known as amyloid-related imaging abnormalities, or ARIA. The abnormalities, which typically only affect a very small area of the brain, appear on brain scans and indicate swelling or bleeding. In clinical trials of lecanemab, 12.6% of participants experienced ARIA and most cases were asymptomatic and resolved without intervention. A small percentage (2.8%) experienced symptoms such as headaches, confusion, nausea and dizziness. Occasional deaths have been linked to lecanemab in an estimated 0.2% of patients treated.

The Memory Diagnostic Center began treating patients with lecanemab in 2023 after the drug received full FDA approval. Patients receive the medication via infusions every two weeks in infusion centers. As part of each patient’s care, WashU Medicine doctors regularly gather sophisticated imaging to monitor the brain, which can detect bleeding and swelling with great sensitivity. Lecanemab is discontinued in patients with symptoms from ARIA or significant ARIA without symptoms, and the rare patients with severe ARIA are treated with steroids in the hospital.

In looking back on their patients’ outcomes, the authors found the extent of side effects aligned with those of the trials – most of the clinic’s cases of ARIA were asymptomatic and only discovered on sensitive brain scans used to monitor brain changes. Of the 11 patients who experienced symptoms from ARIA, the effects largely resolved within a few months and no patients died.

“Most patients on lecanemab tolerate the drug well,” said Suzanne Schindler, MD, PhD, an associate professor of neurology and a co-senior author of the study. “This report may help patients and providers better understand the risks of treatment, which are lower in patients with very mild symptoms of Alzheimer’s.”

Source: WashU Medicine