Strongest Evidence Yet of Brain’s Compensation for Cognitive Decline in Aging

Scientists have found the strongest evidence yet that our brains can compensate for age-related deterioration by recruiting other areas to help with brain function and maintain cognitive performance.

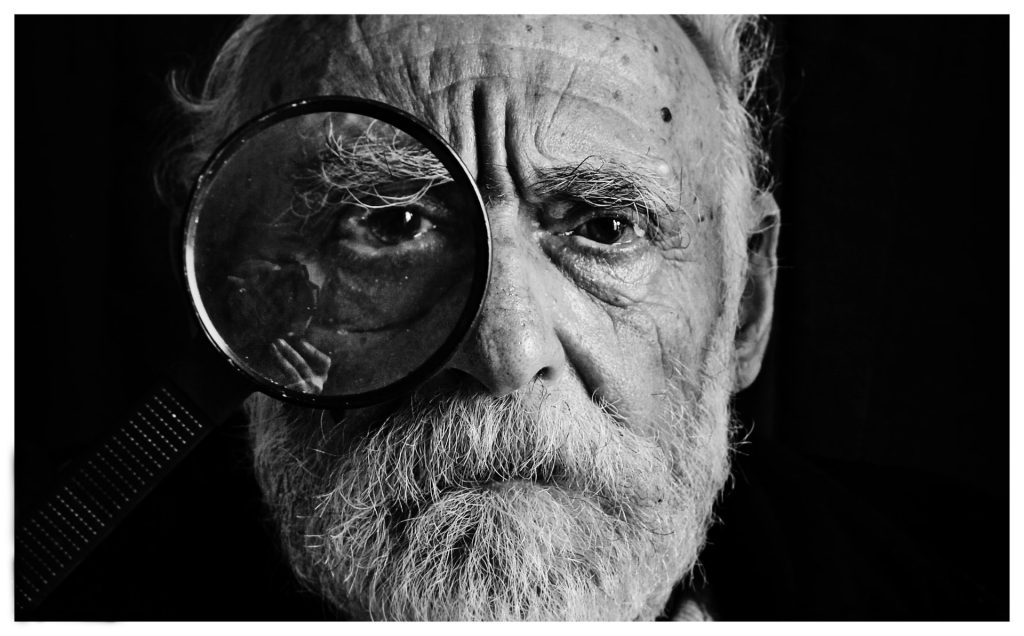

As we age, our brain gradually atrophies, losing nerve cells and connections and this can lead to a decline in brain function. It’s not fully understood why some people appear to maintain better brain function than others, and how we can protect ourselves from cognitive decline.

A widely accepted notion is that some people’s brains are able to compensate for the deterioration in brain tissue by recruiting other areas of the brain to help perform tasks. While brain imaging studies have shown that the brain does recruit other areas, until now it has not been clear whether this makes any difference to performance on a task, or whether it provides any additional information about how to perform that task.

In a study published in the journal eLife, a team led by scientists at the University of Cambridge in collaboration with the University of Sussex have shown that when the brain recruits other areas, it improves performance specifically in the brains of older people.

Study lead Dr Kamen Tsvetanov, an Alzheimer’s Society Dementia Research Leader Fellow in the Department of Clinical Neurosciences, University of Cambridge, said: “Our ability to solve abstract problems is a sign of so-called ‘fluid intelligence’, but as we get older, this ability begins to show significant decline. Some people manage to maintain this ability better than others. We wanted to ask why that was the case – are they able to recruit other areas of the brain to overcome changes in the brain that would otherwise be detrimental?”

Brain imaging studies have shown that fluid intelligence tasks engage the ‘multiple demand network’ (MDN), a brain network involving regions both at the front and rear of the brain, but its activity decreases with age. To see whether the brain compensated for this decrease in activity, the Cambridge team looked at imaging data from 223 adults between 19 and 87 years of age who had been recruited by the Cambridge Centre for Ageing & Neuroscience (Cam-CAN).

The volunteers were asked to identify the odd-one-out in a series of puzzles of varying difficulty while lying in a functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) scanner, so that the researchers could look at patterns of brain activity by measuring changes in blood flow.

As anticipated, in general the ability to solve the problems decreased with age. The MDN was particularly active, as were regions of the brain involved in processing visual information.

When the team analysed the images further using machine-learning, they found two areas of the brain that showed greater activity in the brains of older people, and also correlated with better performance on the task. These areas were the cuneus, at the rear of the brain, and a region in the frontal cortex. But of the two, only activity in the cuneus region was related to performance of the task more strongly in the older than younger volunteers, and contained extra information about the task beyond the MDN.

Although it is not clear exactly why the cuneus should be recruited for this task, the researchers point out that this brain region is usually good at helping us stay focused on what we see. Older adults often have a harder time briefly remembering information that they have just seen, like the complex puzzle pieces used in the task. The increased activity in the cuneus might reflect a change in how often older adults look at these pieces, as a strategy to make up for their poorer visual memory.

Dr Ethan Knights from the Medical Research Council Cognition and Brain Sciences Unit at Cambridge said: “Now that we’ve seen this compensation happening, we can start to ask questions about why it happens for some older people, but not others, and in some tasks, but not others. Is there something special about these people – their education or lifestyle, for example – and if so, is there a way we can intervene to help others see similar benefits?”

Dr Alexa Morcom from the University of Sussex’s School of Psychology and Sussex Neuroscience research centre said: “This new finding also hints that compensation in later life does not rely on the multiple demand network as previously assumed, but recruits areas whose function is preserved in ageing.”

The original text of this story is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

Source: University of Cambridge