Secrets of Pregnant Mothers’ ‘Super Antibodies’ Revealed

Pregnant mothers have the ability to confer greater immunity to the vulnerable developing foetus with ‘super antibodies’. Now, a far-reaching study published in Nature provides a surprising explanation of how this actually works, and what it could mean for preventing death and disability from a wide range of infectious diseases.

The findings suggest the amped-up antibodies that expecting mothers produce could be mimicked to create new drugs to treat diseases as well as improved vaccines to prevent them.

“For many years, scientists believed that antibodies cannot get inside cells. They don’t have the necessary machinery. And so, infections caused by pathogens that live exclusively inside cells were thought to be invisible to antibody-based therapies,” said Sing Sing Way, MD. “Our findings show that pregnancy changes the structure of certain sugars attached to the antibodies, which allows them to protect babies from infection by a much wider range of pathogens.”

“The maternal-infant dyad is so special. It’s the intimate connection between a mother and her baby,” says John Erickson, MD, PhD, first-author of the study.

Drs Way and Erickson are both part of Cincinnati Children’s Center for Inflammation and Tolerance and the Perinatal Institute, which strives to improve outcomes for all pregnant women and their newborns.

Erickson continues, “This special connection starts when babies are in the womb and continues after birth. I love seeing the closeness between mothers and their babies in our newborn care units. This discovery paves the way for pioneering new therapies that can specifically target infections in pregnant mothers and newborns babies. I believe these findings also will have far-reaching implications for antibody-based therapies in other fields.”

How mothers make super antibodies

The new study identifies the specific change in the sugar. During pregnancy, the “acetylated” form of sialic acid (one of the sugars attached to antibodies) shifts to the “deacetylated” form. This subtle molecular shift lets immunoglobulin G (IgG) take on an expanded protective role by stimulating immunity through receptors that respond specifically to deacetylated sugars.

“This change is the light switch that allows maternal antibodies to protect babies against infection inside cells,” Dr Way said.

“Mothers always seem to know best,” Dr Erickson added.

Revved-up antibodies can be produced in the lab

The research team pinned down the key biochemical differences between antibodies in virgin mice compared to pregnant ones. They also identified the enzyme naturally expressed during pregnancy responsible for driving this transformation.

Further, the team successfully restored lost immune protection by supplying lab-grown supplies of the antibodies from healthy pregnant mice to pups born to mothers that were gene-edited to lack the ability to remove acetylation from antibodies to enhance protection.

Hundreds of monoclonal antibodies have been produced as potential treatments for various disorders, including COVID, with a variety of results.

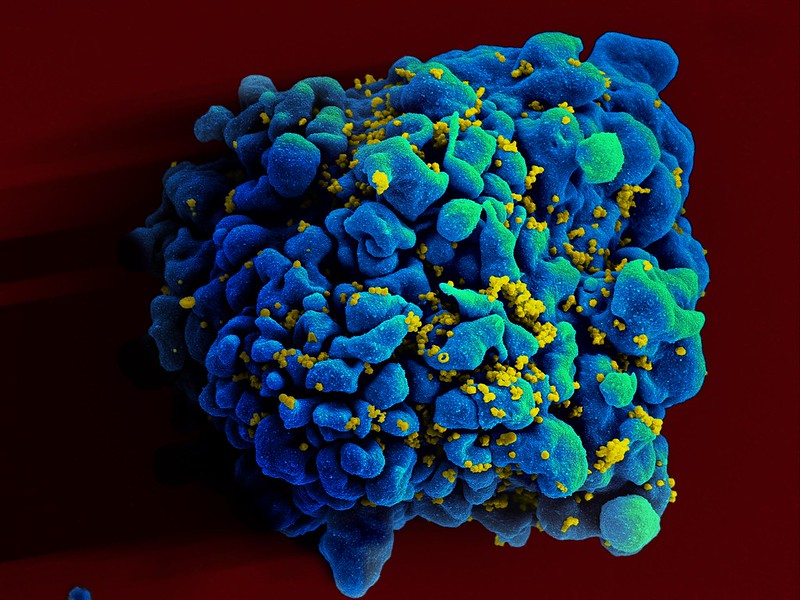

Dr Way said this molecular alteration can be replicated to change how antibodies stimulate the immune system to fine-tune their effects. This potentially could lead to improved treatments for infections caused by other intracellular pathogens including HIV and respiratory syncytial virus (RSV), a common virus that poses serious risks to infants.

Another reason to accelerate vaccine development

“We’ve known for years the many far-reaching benefits of breastfeeding,” Dr Erickson said. “One major factor is the transfer of antibodies in breastmilk.”

The study shows that nursing mothers retain the molecular switch, passing through the antibodies to their newborns.

Additionally, Dr Way says the findings underscore the importance of receiving all available vaccines for women of reproductive age – as well as the need for researchers to develop even more vaccines against infections that which are especially prominent in women during pregnancy or in newborn babies.

“The immunity needs to exist within the mother for it to be transferred to her child,” Dr Way said. “Without natural exposures or immunity primed by vaccination, when that light switch flips during pregnancy, there’s no electricity behind it.”