Two New Antibodies to Treat Inflammatory Autoimmune Diseases

An international research group directed by UMC Utrecht have developed and characterised two first-in-class antibodies that specifically block the high-affinity IgG receptor FcγRI. Their findings open new perspectives for therapeutic modulation of FcγRI-driven inflammation in autoimmune diseases such as rheumatoid arthritis (RA), systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) and immune thrombocytopenia (ITP).

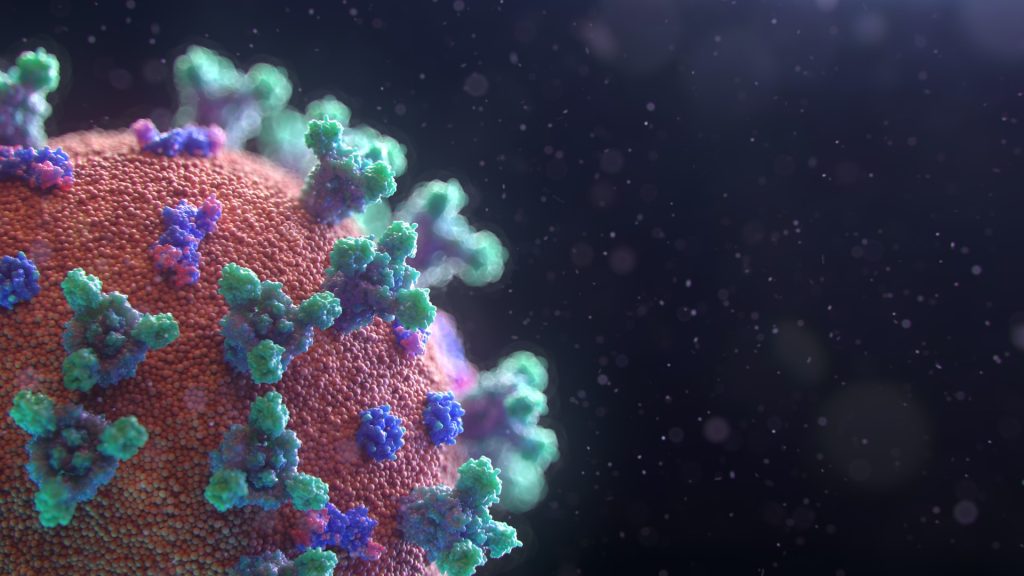

FcγRI, also known as CD64, is a high-affinity receptor on myeloid cells that binds to the Fc region of immunoglobulin G (IgG) antibodies. It plays a key role in immune defence by triggering cellular functions such as phagocytosis and cytokine production. In a normal immune response, FcγRI is activated by immune complexes – clusters of antibodies bound to pathogens, which mark them for clearance. In autoimmune diseases, however, the immune system mistakenly targets the body’s own tissues (such as joint proteins in RA, nuclear antigens in SLE, or platelets in ITP), which results in the production of autoantibodies that form immune complexes. These misdirected complexes activate FcγRI unnecessarily, driving chronic inflammation and subsequent tissue damage.

The study, led by Prof Jeanette Leusen, PhD from the Antibody Therapy research group at the Center for Translational Immunology (UMC Utrecht) and carried out by PhD candidate Tosca Holtrop MSc, was a true team effort, in collaboration with experts from Kiel University (Germany), Leiden University Medical Center, Utrecht University, and Friedrich-Alexander University Erlangen-Nürnberg (Germany).

Discovery of first-in-class antibodies

For over 30 years, scientists have tried to generate antibodies against the IgG-binding domain of CD64, but the receptor’s extremely high affinity for IgG made this impossible with earlier technologies. Combining the UMAB unique immunisation method with novel phage display antibody libraries, the team bypassed this challenge by excluding the Fc region of the antibodies. This allowed them to discover two unique Fc-silent antibodies, C01 and C04, that bind purely via their Fab domains to FcγRI. Crystal structural analysis confirmed that C01 binds precisely within the IgG-binding site on EC2, making binding mutually exclusive.

High affinity for FcγRI

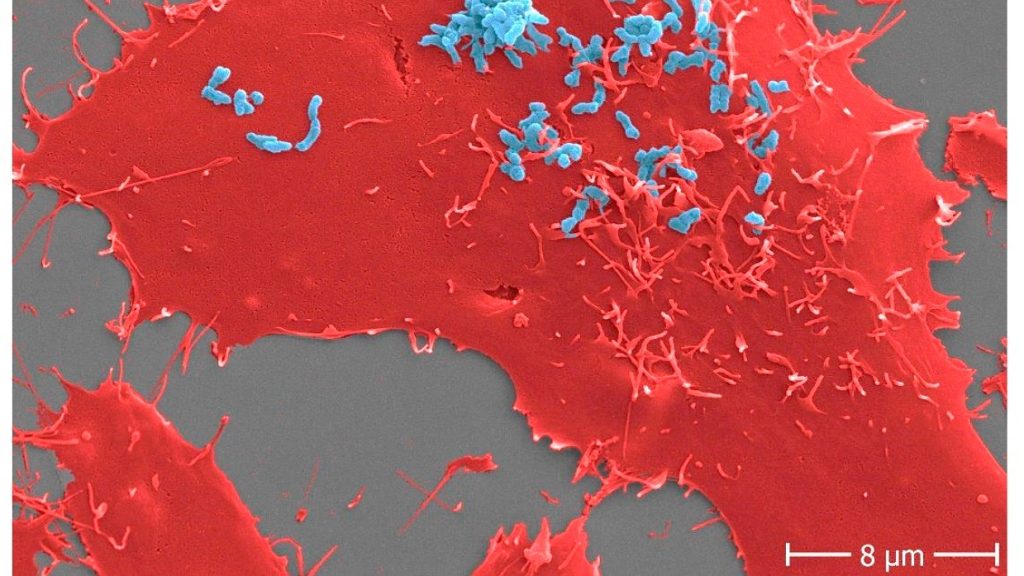

Quantitative binding studies revealed that both antibodies have higher affinity for FcγRI than human IgG, allowing them to efficiently displace IgG or pathogenic immune complexes up to 60 percent and block binding up to 90 percent. Importantly, neither antibody triggered FcγRI activation, a critical distinction from earlier anti-FcγRI antibodies, which could inadvertently trigger receptor clustering and cytokine release.

Subsequently. an in vitro model for immune thrombocytopenia was set-up, where C01 and C04 effectively inhibited opsonized platelets from binding to immune cells from ITP patients. In a preclinical in vivo ITP model, the antibodies significantly reduced IgG-dependent platelet depletion. The antibodies were also tested in an in vitro rheumatoid arthritis models, where they effectively inhibited patient-derived autoantibody–immune complex binding to monocytes, macrophages, and neutrophils from healthy donors.

Promising therapeutic candidate drugs

The study demonstrates that direct Fab-mediated inhibition of FcγRI is feasible and effective, opening a new avenue for treating autoimmune diseases characterised by IgG-autoantibody complexes. By preventing immune complex–driven activation without triggering the receptor, C01 and C04 represent a promising next step toward targeted, inflammation-sparing immunotherapy. “I think we found the needle in the haystack, after searching over a decade and thanks to a true team effort,” says Jeanette Leusen, principal investigator of the study. “Each research partner contributed a critical piece, from antibody discovery and structure determination to patient sample testing and preclinical models. Only together could we bring this to fruition. These antibodies not only provide a unique tool for studying FcγRI biology, but also hold promise as therapeutic candidates in autoimmune and infectious diseases.”