Small Reductions in Cholesterol Could Slash Risk of Dementia for Those with Certain Genetics

Low cholesterol can reduce the risk of dementia, a new University of Bristol-led study with more than a million participants has shown.

The research, led by Dr Liv Tybjærg Nordestgaard while at the University of Bristol and the Department of Clinical Biochemistry at Copenhagen University Hospital – Herlev and Gentofte, found that people with certain genetic variants that naturally lower cholesterol have a lower risk of developing dementia.

The study, which is based on data from over a million people in Denmark, England, and Finland, has been published in the journal Alzheimer’s & Dementia: The Journal of the Alzheimer’s Association.

Some people are born with genetic variants that naturally affect the same proteins targeted by cholesterol-lowering drugs, such as statins and ezetimibe. To test the effect of cholesterol-lowering medication on the risk of dementia, the researchers used a method called Mendelian Randomisation – this genetic analysis technique allowed them to mimic the effects of these drugs to investigate how they influence the risk of dementia, while minimising the influence of confounding factors like weight, diet, and other lifestyle habits.

By comparing these individuals to individuals without these genetic variants, the researchers were able to measure differences in the risk of dementia. They found reducing the amount of cholesterol in the blood by a small amount (one millimole per litre) to be associated with up to 80% reduction in risk of developing dementia for certain drug targets.

“What our study indicates is that if you have these variants that lower your cholesterol, it looks like you have a significantly lower risk of developing dementia,” said Dr Nordestgaard, who now works in the Department of Clinical Biochemistry at Copenhagen University Hospital – Bispebjerg and Frederiksberg hospital.

The results suggest that having low cholesterol, whether due to genes or medical treatment, can help reduce the risk of dementia. However, the study does not say anything definitive about the effect of the medicine itself.

One of the challenges is that dementia typically does not appear until late in life, and therefore research in the area typically requires a very long period of follow-up.

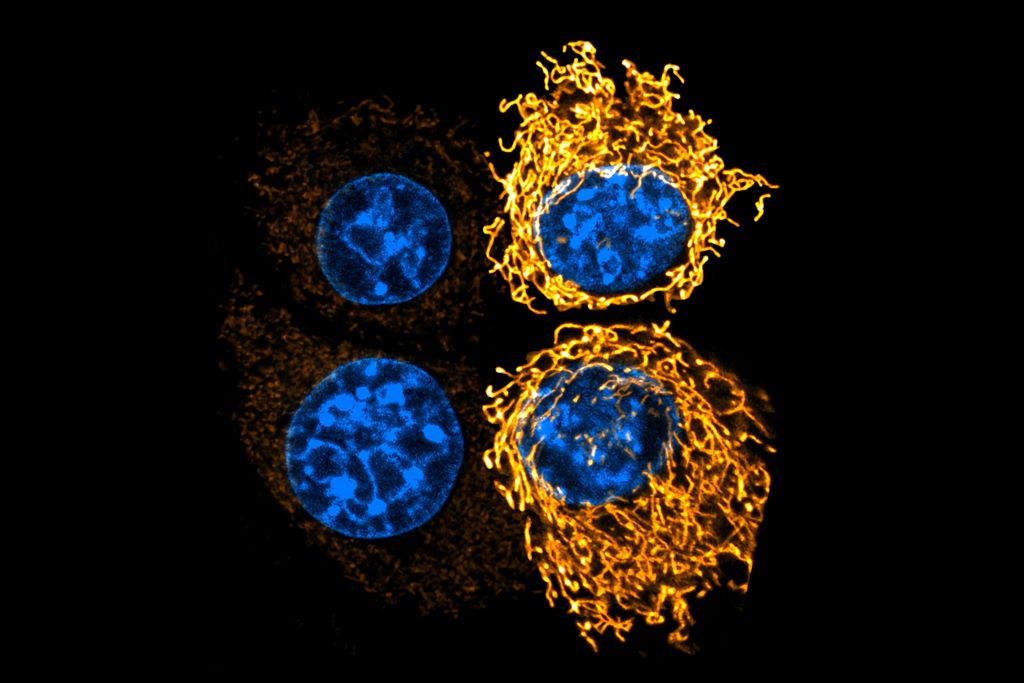

It is still not known exactly why high cholesterol can increase the risk of dementia, but one possible explanation proposed by Dr Nordestgaard is that high cholesterol can lead to atherosclerosis.

“Atherosclerosis is a result of the accumulation of cholesterol in your blood vessels,” Dr Nordestgaard said. “It can be in both the body and the brain and increases the risk of forming small blood clots – one of the causes of dementia.

“It would be a really good next step to carry out randomised clinical trials over 10 or 30 years, for example, where you give the participants cholesterol-lowering medication and then look at the risk of developing dementia,” Dr Nordestgaard added.

The study used data from the UK Biobank, the Copenhagen General Population Study, the Copenhagen City Heart Study, the FinnGen study, and the Global Lipids Genetics Consortium.

Source: University of Bristol