UK Study Proves Effectiveness of Childhood Type 1 Diabetes Screening

Thousands of families have taken part in a landmark UK study led by researchers at the University of Birmingham which shows that childhood screening for type 1 diabetes is effective, laying the groundwork for a UK-wide childhood screening programme.

Results from the first phase of the ELSA (Early Surveillance for Autoimmune diabetes) study, co-funded by charities Diabetes UK and Breakthrough T1D, have been published in a research letter in The Lancet Diabetes & Endocrinology today.

The findings mark a major step towards a future in which type 1 diabetes can be detected in children before symptoms appear. Currently, over a quarter of children aren’t diagnosed with type 1 diabetes until they are in diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA), a potentially fatal condition that requires urgent hospital treatment. Early detection can dramatically reduce emergency diagnoses and could give children access to new immunotherapy treatments that can delay the need for insulin for years.

We are working towards a future where type 1 diabetes can be detected in a timely manner

Professor Parth Narendran, lead researcher

Launched in 2022, ELSA is the first UK study of its kind, tested blood samples from 17,931 children aged 3-13 for autoantibodies, markers of type 1 diabetes that can appear years before symptoms.

Children without autoantibodies are unlikely to develop type 1 diabetes, while those with one autoantibody have a 15% chance of developing the condition within 10 years. Having two or more autoantibodies indicates the immune system has already started attacking the insulin-producing cells in the pancreas and it is almost certain these children will eventually need insulin therapy. This is known as early-stage type 1 diabetes.

Among the 17,283 children aged 3-13 years who were screened for type 1 diabetes risk at the time of analysis:

- 75 had one autoantibody, signaling increased future risk.

- 160 had two or more autoantibodies but did not yet require insulin therapy, indicating early-stage type 1 diabetes.

- 7 were found to have undiagnosed type 1 diabetes with all needing to start insulin immediately.

Lead researcher, Parth Narendran, Professor of Diabetes Medicine at the University of Birmingham, said: “We are extremely grateful to all the families who have participated in the study and generously given their time to help understand how a UK-wide screening programme could be developed. Together with Diabetes UK, Breakthrough T1D and the National Institute for Health and Care Research, we are working towards a future where type 1 diabetes can be detected in a timely manner, and families appropriately supported and treated with medicines to delay the need for insulin.

“We are also grateful to partners across the Birmingham Health and Life Sciences District and beyond as well as the NIHR for the support they have provided in getting us to where we are.”

Interventions before diagnosis

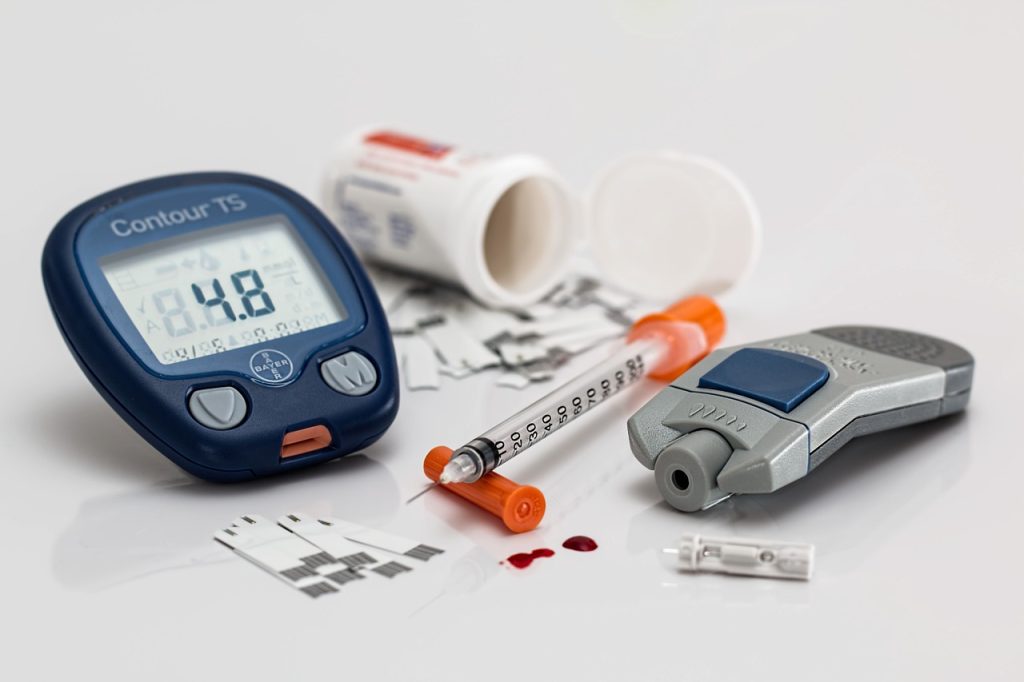

Families of children found to have early-stage type 1 diabetes received tailored education and ongoing support to prepare for the eventual onset of type 1 diabetes symptoms and to ensure insulin therapy can begin promptly when needed, reducing the chances of needing emergency treatment. Those with one autoantibody also received ongoing support and monitoring.

Some families were also offered teplizumab, the first ever immunotherapy for type 1 diabetes, which can delay the need for insulin by around three years in people with early-stage type 1 diabetes. The first patient was treated at Birmingham Children’s Hospital. Teplizumab was licensed by the Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA) in the UK in August 2025, and is currently being assessed by the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) to determine whether it should be available through the NHS.

As of November 2025, more than 37,000 families have signed up to the ELSA programme. Building on this strong foundation, the second phase of the research, ELSA 2, launches today. ELSA 2 will expand screening to all children in the UK aged 2-17 years, with a focus on younger children (2-3 years) and older teenagers (14-17 years). The research team aims to recruit 30,000 additional children across these new age groups.

ELSA 2 will also establish new NHS Early-Stage Type 1 Diabetes Clinics, providing families taking part with clinical and psychological support and creating a clear pathway from screening to diagnosis, monitoring and treatment.

Case study: Knowing what’s coming … has made an enormous difference

Amy Norman, 44, from the West Midlands, was diagnosed with type 1 diabetes at the age of 13. She recently discovered via the ELSA study that her 11-year-old daughter, Imogen, is in the early stages of type 1 diabetes but has been able to slow its progression as the second child in the UK to access a breakthrough immunotherapy drug – teplizumab. She said: “Being part of the ELSA study has helped us as a family to prepare for the future in a way we never expected. Knowing what’s coming – rather than being taken by surprise – has made an enormous difference to our confidence and peace of mind.

“When I was diagnosed, I had no warning and ended up quite poorly in hospital with diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA). When Imogen’s diagnosis arrives, we hope that having this awareness will reduce her chances of experiencing DKA and the added trauma that comes from a sudden illness.

“Imogen took part in the study to further research and help others, but it has helped her too – being forewarned is being forearmed. She was always going to develop type 1 diabetes, but through ELSA we’ve been able to slow down the process and prepare – we know what is coming, but we’re not scared.”

A game-changer: showing what we can achieve in Birmingham

Professor Neil Hanley, Pro-Vice-Chancellor and Head of the College of Medicine and Health at the University of Birmingham, said, “This is a game-changer. This trial shows we can spare countless children the trauma of an emergency diagnosis, ensure they get early support, and potentially give them access to revolutionary new treatments that could delay or even prevent type 1 diabetes.

“Dr Parth Narendran and his team deserve huge credit; and this breakthrough shows what we can achieve in Birmingham. We have world-class clinicians and scientists working side-by-side, backed by great innovation infrastructure and a vibrant, diverse and affordable city – and, as a result, we are changing lives with next generation diagnostics, therapeutics, and clinical care.”

Rewriting the story of type 1 diabetes

Dr Elizabeth Robertson, Director of Research and Clinical at Diabetes UK, said: “For too many families, a child’s type 1 diabetes diagnosis still comes as a frightening emergency. But that doesn’t have to be the case. Thanks to scientific breakthroughs, we now have the tools to identify children in the very earliest stages of type 1 diabetes – giving families precious time to prepare, avoid emergency hospital admissions, and access treatments that can delay the need for insulin for years.

“The ELSA study, co-funded by Diabetes UK, is generating the evidence needed to make type 1 diabetes screening a reality for every family in the UK. We’re incredibly grateful to the 37,000 families who’ve already signed up and urge others to get involved. Together, we can transform type 1 diabetes care for future generations.”

Rachel Connor, Director of Research Partnerships at Breakthrough T1D, said: “This is about rewriting the story of type 1 diabetes for thousands of families. Instead of a devastating emergency, we can offer time, choices, and hope. By finding children in the earliest stages, we’re not just preparing families, we’re opening the door to treatments that can delay the need for insulin by years. That extra time means childhoods with fewer injections, fewer hospital visits and more normality. Thanks to research like ELSA, what once struck as an unexpected crisis can become an actively managed healthcare process, changing the course of T1D for the better.”

The findings from ELSA’s first phase signal a major step towards a future in which type 1 diabetes can be detected early, managed proactively, and potentially delayed through immunotherapy. ELSA demonstrates that childhood screening in the UK is feasible, acceptable to families, and capable of preventing emergency diagnoses. Continued research through ELSA 2 will assess how screening can be scaled across the NHS and evaluate its cost-effectiveness.

Source: University of Birmingham