Human Instruction with AI Guidance Gives the Best Results in Neurosurgical Training

Study has implications beyond medical education, suggesting other fields could benefit from AI-enhanced training

Artificial intelligence (AI) is becoming a powerful new tool in training and education, including in the field of neurosurgery. Yet a new study suggests that AI tutoring provides better results when paired with human instruction.

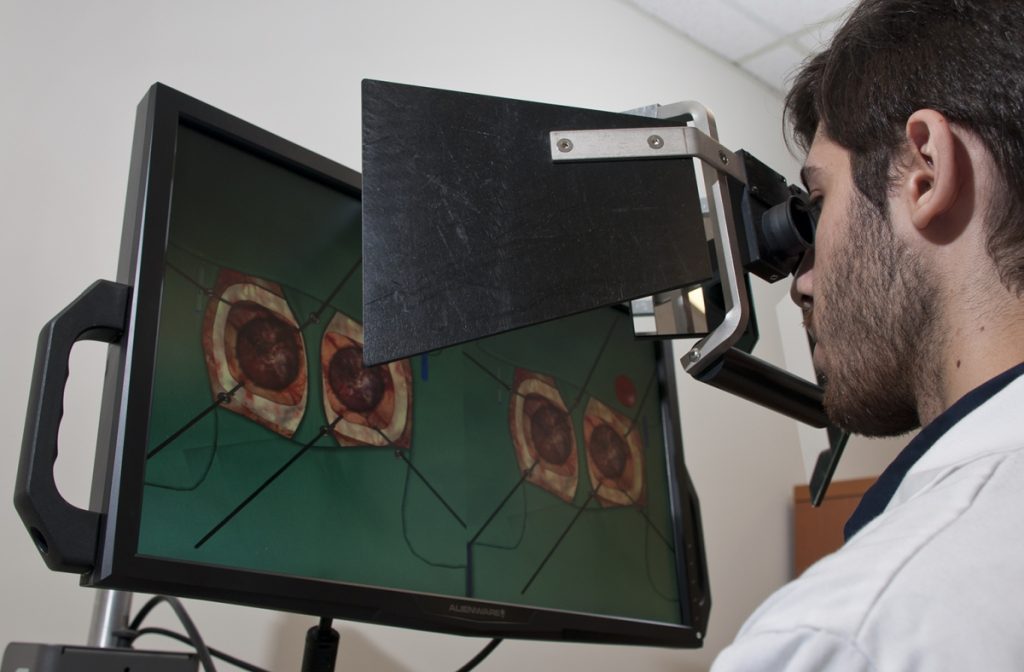

Researchers at the Neurosurgical Simulation and Artificial Intelligence Learning Centre at The Neuro (Montreal Neurological Institute-Hospital) of McGill University are studying how AI and virtual reality (VR) can improve the training and performance of brain surgeons. They simulate brain surgeries using VR, monitor students’ performance using AI and provide continuous verbal feedback on how students can improve performance and prevent errors. Previous research has shown that an intelligent tutoring system powered by AI developed at the Centre outperformed expert human teachers, but these instructors were not provided with trainee AI performance data.

In their most recent study, published in JAMA Surgery, the researchers recruited 87 medical students from four Quebec medical schools and divided them into three groups: one trained with AI-only verbal feedback, one with expert instructor feedback, and one with expert feedback informed by real-time AI performance data. The team recorded the students’ performance, including how well and how quickly their surgical skills improved while undergoing the different types of training.

They found that students receiving AI-augmented, personalised feedback from a human instructor outperformed both other groups in surgical performance and skill transfer. This group also demonstrated significantly better risk management for bleeding and tissue injury – two critical measures of surgical expertise. The study suggests that while intelligent tutoring systems can provide standardised, data-driven assessments, the integration of human expertise enhances engagement and ensures that feedback is contextualised and adaptive.

“Our findings underscore the importance of human input in AI-driven surgical education,” said lead study author Bianca Giglio. “When expert instructors used AI performance data to deliver tailored, real-time feedback, trainees learned faster and transferred their skills more effectively.”

While this study was specific to neurosurgical training, its findings could carry over to other professions where students must acquire highly technical and complex skills in high-pressure environments.

“AI is not replacing educators – it’s empowering them,” added senior author Dr Rolando Del Maestro, a neurosurgeon and current Director of the Centre. “By merging AI’s analytical power with the critical guidance of experienced instructors, we are moving closer to creating the ‘Intelligent Operating Room’ of the future capable of assessing and training learners while minimising errors during human surgical procedures.”

Source: McGill University