New Approach to MS ‘Teaches’ Immune Cells not to Attack

Researchers from have found a potential new way to improve the treatment of multiple sclerosis (MS) using a novel combined therapy. The results, published in the Journal of Clinical Investigation, builds on two harmonised Phase I clinical trials, focusing on the use of Vitamin D3 tolerogenic dendritic cells (VitD3-tolDCs) to regulate the immune response in MS patient.

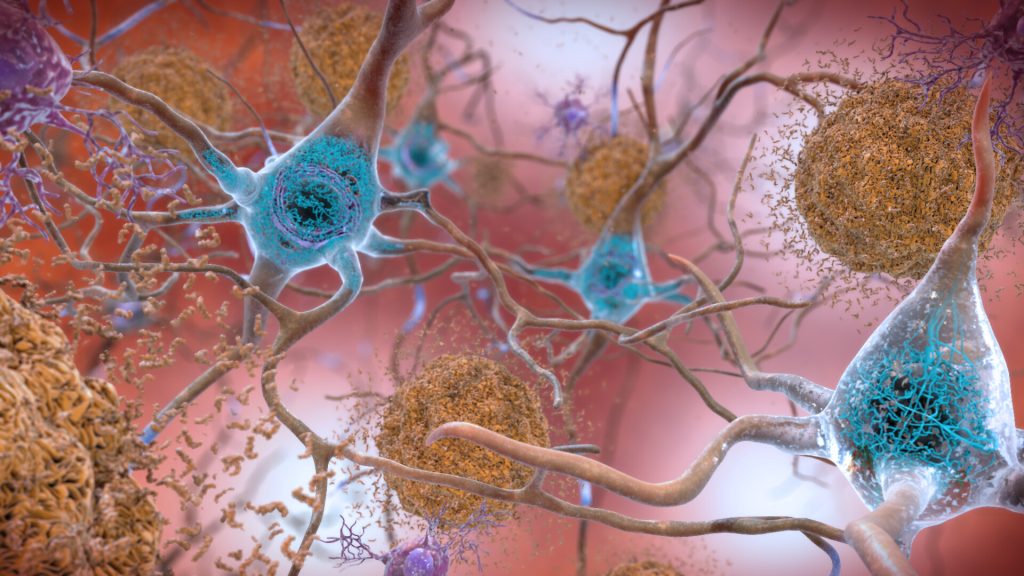

Multiple Sclerosis (MS) is a long-term disease where the immune system mistakenly attacks the protective myelin sheath around nerve cells. This leads to nerve damage and worsening disability. Current treatments, like immunosuppressants, help reduce these harmful attacks but also weaken the overall immune system, leaving patients vulnerable to infections and cancer. Scientists are now exploring a more targeted therapy using special immune cells, called tolerogenic dendritic cells (tolDCs), from the same patients.

TolDCs can restore immune balance without affecting the body’s natural defences. However, since a hallmark of MS is precisely the dysfunction of the immune system, the effectiveness of these cells for auto transplantation might be compromised. Therefore, it is essential to better understand how the disease affects the starting material for this cellular therapy before it can be applied.

In this study, researchers from Barcelona’s Germans Trias i Pujol Institute and Josep Carreras Leukaemia Research Institute, examined CD14+ monocytes, mature dendritic cells (mDCs), and Vitamin D3-treated tolerogenic dendritic cells (VitD3-tolDCs) from MS patients who had not yet received treatment, as well as from healthy individuals. The clinical trials (NCT02618902 and NCT02903537) are designed to assess the effectiveness of VitD3-tolDCs, which are loaded with myelin antigens to help “teach” the immune system to stop attacking the nervous system. This approach is groundbreaking as it uses a patient’s own immune cells, modified to induce immune tolerance, in an effort to treat the autoimmune nature of MS.

The study, led by Dr Eva Martinez-Cáceres and Dr Esteban Ballestar, with Federico Fondelli as first author, found that the immune cells from MS patients (monocytes, precursors of tolDCs) have a persistent “pro-inflammatory” signature, even after being transformed into VitD3-tolDCs, the actual therapeutic cell type. This signature makes these cells less effective compared to those derived from healthy individuals, missing part of its potential benefits.

Using state-of-the-art research methodologies, the researchers identified a pathway, known as the Aryl Hydrocarbon Receptor (AhR), that is linked to this altered immune response. By using an AhR-modulating drug, the team was able to restore the normal function of VitD3-tolDCs from MS patients, in vitro. Interestingly, Dimethyl Fumarate, an already approved MS drug, was found to mimic the effect of AhR modulation and restore the cells’ full efficacy, with a safer toxic profile.

Finally, studies in MS animal models showed that a combination of VitD3-tolDCs and Dimethyl Fumarate led to better results than using either treatment on its own. This combination therapy significantly reduced symptoms in mice, suggesting enhanced potential for treating human patients.

These results could lead to a new, more potent treatment option for multiple sclerosis, offering hope to the millions of patients worldwide who suffer from this debilitating disease. This study represents a significant step forward in the use of personalised cell therapies for autoimmune diseases, potentially revolutionising how multiple sclerosis is treated.

The team is now preparing to move into Phase II trials to further explore these findings.