Hidden Genetic Risk Could Delay Diabetes Diagnosis for Black and Asian Men

A common but often undiagnosed genetic condition may be causing delays in type 2 diabetes diagnoses and increasing the risk of serious complications for thousands of Black and South Asian men in the UK – and potentially millions worldwide.

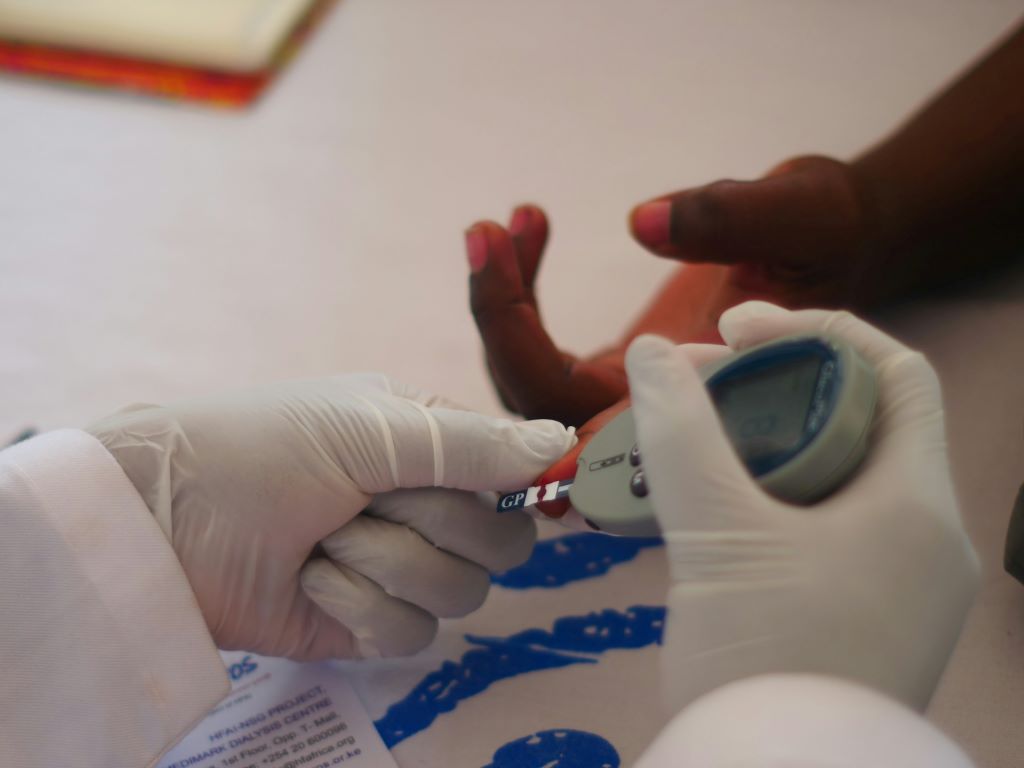

The new study is conducted by the University of Exeter, in collaboration with Queen Mary University of London (QMUL). The findings, published in Diabetes Care, show that around one in seven Black and one in 63 South Asian men in the UK carry a genetic variant known as G6PD deficiency. Men with G6PD deficiency are, on average, diagnosed with type 2 diabetes four years later than those without the gene variant. But despite this, fewer than one in 50 have been diagnosed with the condition

G6PD deficiency does not cause diabetes, but it makes the widely used HbA1c blood test – which diagnoses and monitors diabetes – appear artificially low. This can mislead doctors and patients, resulting in delayed diabetes diagnosis and treatment.

Professor Inês Barroso from the University of Exeter said: “Our findings highlight the urgent need for changes to testing practices to tackle health inequalities. Doctors and health policy makers need to be aware that the HbA1c test may not be accurate for people with G6PD deficiency and routine G6PD screening could help identify those at risk. Addressing this issue is not only crucial for medicine, but for health equity.”

G6PD deficiency is a genetic condition that affects more than 400 million people worldwide, and is especially prevalent among those with African, Asian, Middle Eastern, and Mediterranean backgrounds. It is more common in men and usually goes undetected because it rarely causes symptoms. The World Health Organization recommends routine screening for G6PD deficiency in populations where it is common, but this is not widely implemented in the UK or many other countries.

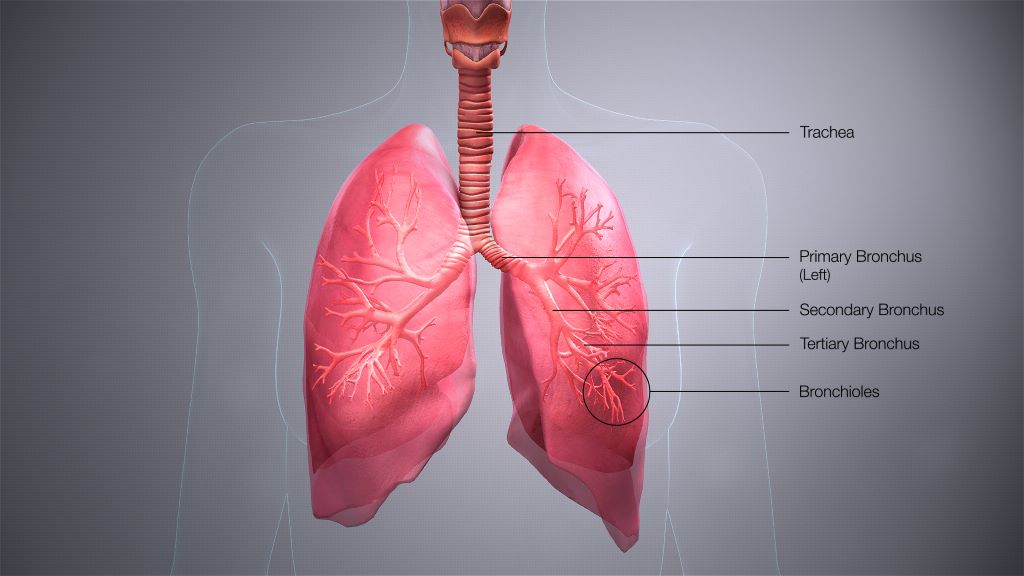

This new study, supported by the National Institute for Health and Care Research Exeter Biomedical Research Centre, has found men with G6PD deficiency are at a 37% higher risk of developing diabetes-related microvascular complications, such as eye, kidney, and nerve damage, compared to other men with diabetes.

The HbA1c blood test is the international standard for managing type 2 diabetes and is used in 136 countries worldwide to diagnose diabetes, including being the routine test for diagnosis in the UK. However, for people with G6PD deficiency, this test may underestimate their blood sugar levels, causing significant medical delays and increasing their risk of serious complications.

Dr Veline L’Esperance, a GP and Senior Clinical Research Fellow at QMUL, said: “These findings are deeply concerning because they show how a widely used diagnostic tool may be failing communities that are already disproportionately affected by type 2 diabetes. Too many people are being left undiagnosed until it is too late to prevent serious complications. We need greater awareness among healthcare professionals and stronger policies to ensure equitable screening and diagnosis. That is why we are launching ‘Black Health Legacy’, which aims to be the largest health research programme focused on tackling diseases that disproportionately affect people from Black backgrounds. This is about saving lives and tackling long-standing inequalities in our healthcare system.”

The findings are based on genetic and health data from over half a million people in UK Biobank and Genes & Health studies. The research was conducted by a multidisciplinary team of clinicians and scientists, with the support of community partners, who linked the genetic data from each participant to their medical information. By doing this the team found men with the G6PD deficiency genetic variant were diagnosed at an older age compared to those without the condition. In addition, those with G6PD deficiency and diabetes also had more diabetes related complications. Researchers say further studies in more diverse populations are now needed to confirm these findings globally.

More information about Black Health Legacy can be found at https://blackhealthlegacy.org

Source: Exeter University