Baby with Rare, Incurable Disease is First to Receive Personalised Gene Therapy

NIH-supported gene-editing platform lays groundwork to rapidly develop treatments for other rare genetic diseases.

A research team supported by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) has developed and safely delivered a personalised gene editing therapy to treat an infant with a life-threatening, incurable genetic disease. The infant, who was diagnosed with the rare condition carbamoyl phosphate synthetase 1 (CPS1) deficiency shortly after birth, has responded positively to the treatment.

The process, from diagnosis to treatment, took only six months and marks the first time the technology has been successfully deployed to treat a human patient. The technology used in this study was developed using a platform that could be tweaked to treat a wide range of genetic disorders and opens the possibility of creating personalised treatments in other parts of the body.

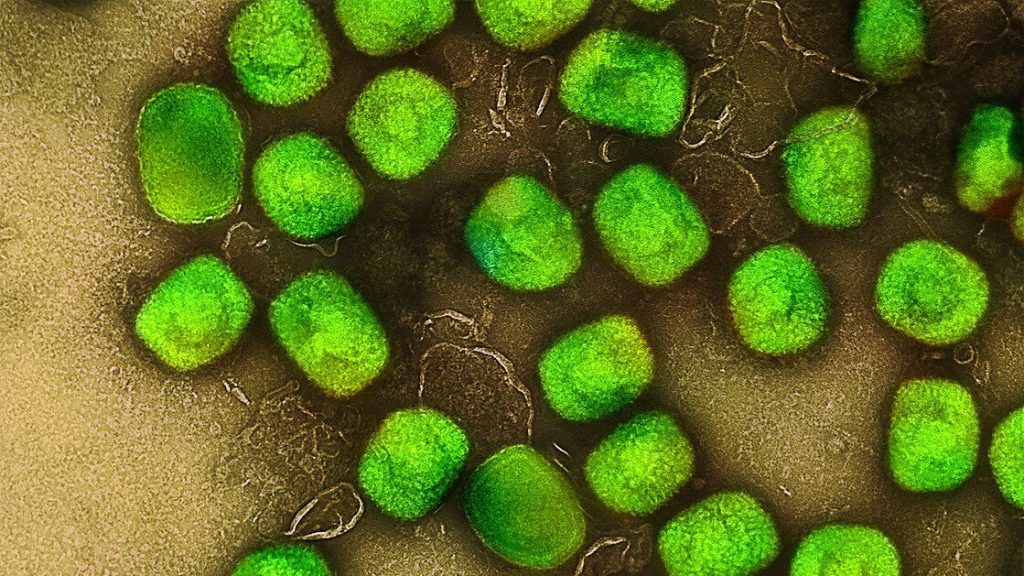

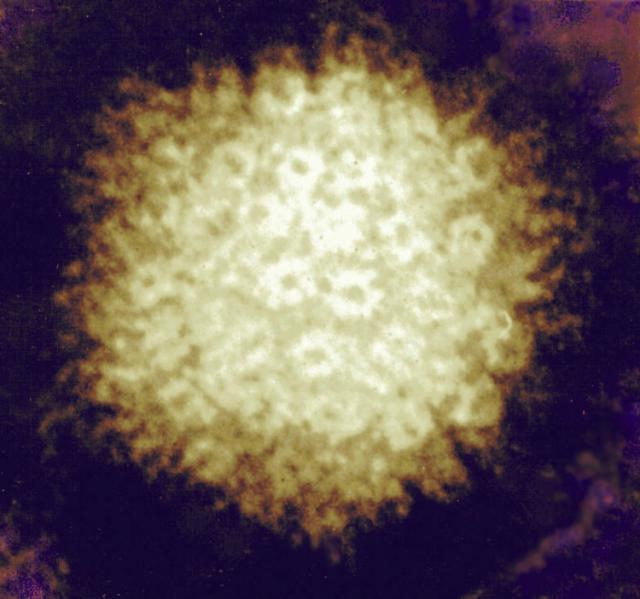

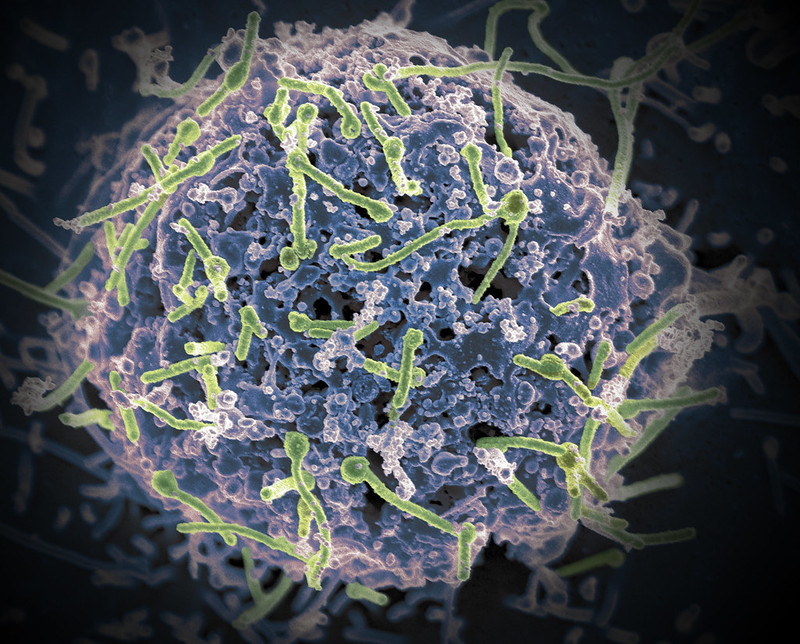

A team of researchers at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia (CHOP) and the Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania (Penn) developed the customised therapy using the gene-editing platform CRISPR. They corrected a specific gene mutation in the baby’s liver cells that led to the disorder. CRISPR is an advanced gene editing technology that enables precise changes to DNA inside living cells. This is the first known case of a personalised CRISPR-based medicine administered to a single patient and was carefully designed to target non-reproductive cells so changes would only affect the patient.

“As a platform, gene editing – built on reusable components and rapid customisation – promises a new era of precision medicine for hundreds of rare diseases, bringing life-changing therapies to patients when timing matters most: Early, fast, and tailored to the individual,” said Joni L. Rutter, Ph.D., director of NIH’s National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS).

CPS1 deficiency is characterized by an inability to fully break down byproducts from protein metabolism in the liver, causing ammonia to build up to toxic levels in the body. It can cause severe damage to the brain and liver. Treatment includes a low protein diet until the child is old enough for a liver transplant. However, in this waiting period there is a risk of rapid organ failure due to stressors such as infection, trauma, or dehydration. High levels of ammonia can cause coma, brain swelling, and may be fatal or cause permanent brain damage.

The child initially received a very low dose of the therapy at six months of age, then a higher dose later. The research team saw signs that the therapy was effective almost from the start. The six-month old began taking in more protein in the diet, and the care team could reduce the medicine needed to keep ammonia levels low in the body. Another telling sign of the child’s improvement to date came after the child caught a cold, and later, had to deal with a gastrointestinal illness. Normally, such infections for a child in this condition could be extremely dangerous, especially with the possibility of ammonia reaching dangerous levels in the brain.

“We knew the method used to deliver the gene-editing machinery to the baby’s liver cells allowed us to give the treatment repeatedly. That meant we could start with a low dose that we were sure was safe,” said CHOP pediatrician Rebecca Ahrens-Nicklas, MD, PhD.

“We were very concerned when the baby got sick, but the baby just shrugged the illness off,” said Penn geneticist and first author Kiran Musunuru, MD, PhD. For now, much work remains, but the researchers are cautiously optimistic about the baby’s progress.

The scientists announced their work at the American Society of Gene & Cell Therapy Meeting on May 15th and described the study in The New England Journal of Medicine.

Source: NIH/Office of the Director