Improving Understanding of Female Sexual Anatomy for Better Pelvic Radiotherapy

Researchers at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, in collaboration with other leading institutions across the country, have published an innovative study that provides radiation oncologists with practical guidance to identify and protect female sexual organs during pelvic cancer treatment.

Published in the latest issue of Practical Radiation Oncology, this study addresses a long-standing gap in cancer care by bringing key female sexual anatomy into consideration during routine radiotherapy planning and survivorship research.

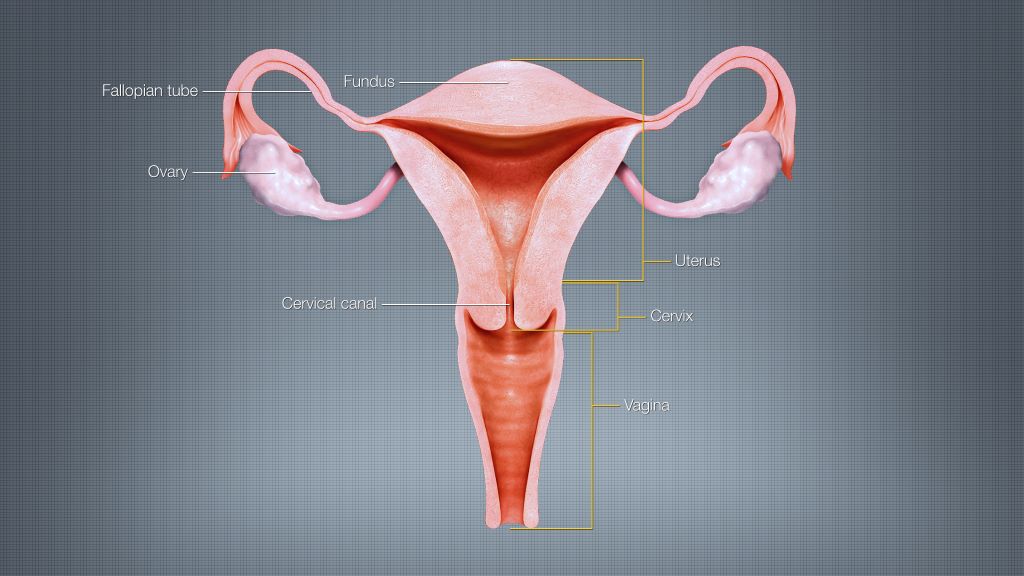

The study, “Getting c-literate: Bulboclitoris functional anatomy and its implications for radiotherapy,” synthesises current scientific knowledge and pairs it with original anatomic dissection, histology, and advanced imaging analysis. The work focuses on the bulboclitoris, a female erectile organ (consisting of the clitoris and the vestibular bulbs) that plays a central role in sexual arousal and orgasm and can be exposed to radiation during treatment for pelvic cancers.

“Pelvic radiotherapy can be life-saving, but it can also affect sexual function and quality of life,” said Deborah Marshall, MD, MAS, Assistant Professor, Departments of Radiation Oncology and Population Health Science and Policy at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai; Division Chief of Women’s Health, Department of Population Health Science and Policy; and senior author of the study. “Compared to male sexual anatomy, female erectile structures have been largely invisible in standard radiation workflows. Our goal was to provide clinicians with a practical anatomy-grounded way to change that.”

Using detailed anatomic and radiologic correlation, the research team demonstrates how the bulboclitoris and related neurovascular structures can be identified on standard CT and MRI scans and consistently outlined (or “contoured”) for radiotherapy planning. This step-by-step guidance makes it feasible for clinicians to measure radiation dose to these tissues and begin linking exposure to patient-reported outcomes related to arousal and orgasm.

“This work builds upon our previous knowledge that the clitoris is not just an external structure,” Dr. Marshall said. “It includes an entire internal organ comprised of erectile tissues located just outside the pelvis, and those tissues matter for sexual health and, in particular, for female sexual pleasure. Once clinicians can reliably see and measure them, we can begin to ask better questions, have better conversations with patients, and ultimately deliver better care.”

Sexual function outcomes after pelvic radiotherapy have historically been understudied in women, limiting counselling, toxicity prevention strategies, and equitable survivorship care. By establishing a shared, standardised approach to identifying the bulboclitoris, the study lays the groundwork for future research to develop dose-volume constraints and mitigation strategies, as other organs at risk are managed in radiation oncology.

For clinicians, the framework enables routine contouring and dose reporting using CT alone when necessary, with MRI improving soft-tissue visualization when available. In the absence of prospective dose-response data, the authors recommend minimising radiation dose to the bulboclitoris when oncologically appropriate, using an “as low as reasonably achievable” approach.

For patients, the work supports more informed conversations about potential sexual side effects of pelvic radiotherapy, including changes in arousal, sensation, orgasm, lubrication, or pain. This research also promotes more personalized treatment planning that considers female sexual health and pleasure as a legitimate and important component of cancer survivorship.

Next steps include prospective research through Mount Sinai’s STAR program, deeper mapping of neurovascular anatomy relevant to sexual function, expanded educational resources for oncology and radiology teams, and improved patient-reported outcome measures that reflect diverse sexual practices and experiences.

Source: Mount Sinai