Kids of Obese Parents More Likely to Develop Obesity due to Inheriting Related Genes

Mom’s genes play a larger role than dad’s in determining whether kids will be obese

A new study finds that kids with obesity are more likely to have obese parents because they inherit obesity-related genes, and to a smaller extent, are impacted indirectly by genes carried by the mother – even when those genes aren’t passed down. A new study led by Liam Wright of the University College London, UK, and colleagues, reports these findings August 5th in the open-access journal PLOS Genetics.

Studies commonly show that children with obesity often have parents with obesity, but the cause of this trend has been poorly understood. Children may inherit genes from their parents that increase their risk of obesity, or they could be shaped by conditions in the womb, or by the food and lifestyle choices their parents make.

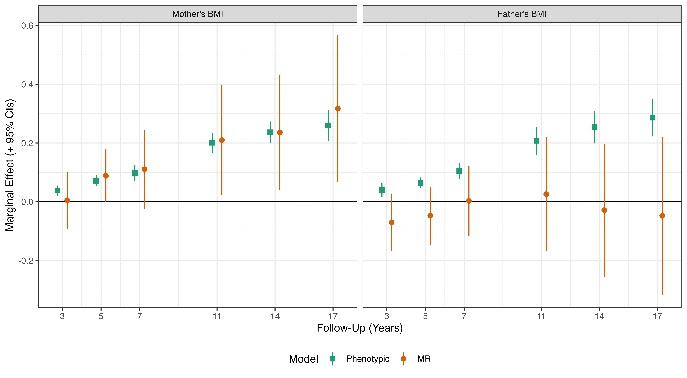

In the new study, researchers investigated the effects of the parents’ genetics on the weight and diet of their children. They looked at a measure of obesity called the body mass index (BMI), along with the diet and genetic data from more than 2500 mother-father-child trios. They focused on obesity related genes in the parents – both the ones that were directly passed down to their children, and the genes that weren’t, but that may indirectly impact weight by shaping the child’s environment, which are called genetic nurture effects. They found that, though mothers’ and fathers’ BMIs were consistently correlated with the child’s BMI, this trend could be mostly explained through the genes that children directly inherit. Genetic nurture effects from obesity-related genes in the mother that were not inherited had a smaller impact, only during the child’s adolescence.

The results suggest that a mother’s BMI may be particularly important for determining a child’s BMI, both due to the effects of genes that children directly inherit, and through indirect nurture effects from genes that weren’t passed down. Meanwhile, fathers had little impact on their child’s BMI, apart from the genes that were directly inherited. The study’s authors suggest that analyses that don’t consider the inherited genes are likely to give misleading estimates of the parents’ influence on a child’s weight.

The authors add, “Our results suggest mother’s weight could affect their children’s weight; policies to reduce obesity could have intergenerational benefits.”

Provided by PLOS