Childhood Experiences Shape White Matter with Cognitive Effects Seen Years Later

Mass General Brigham investigators have linked difficult early life experiences with reduced quality and quantity of the white matter communication highways throughout the adolescent brain. This reduced connectivity is also associated with lower performance on cognitive tasks. However, certain social resiliency factors like neighbourhood cohesion and positive parenting may have a protective effect. Results are published in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS).

White matter are the communication highways that allow the brain networks to carry out the necessary functions for cognition and behaviour. They develop over the course of childhood, and childhood experiences may drive individual differences in how white matter matures. Lead author Sofia Carozza, PhD, and senior author Amar Dhand, MD, PhD, of the Department of Neurology at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, a founding member of the Mass General Brigham healthcare system, wanted to understand what role this process plays in cognition once children reach adolescence.

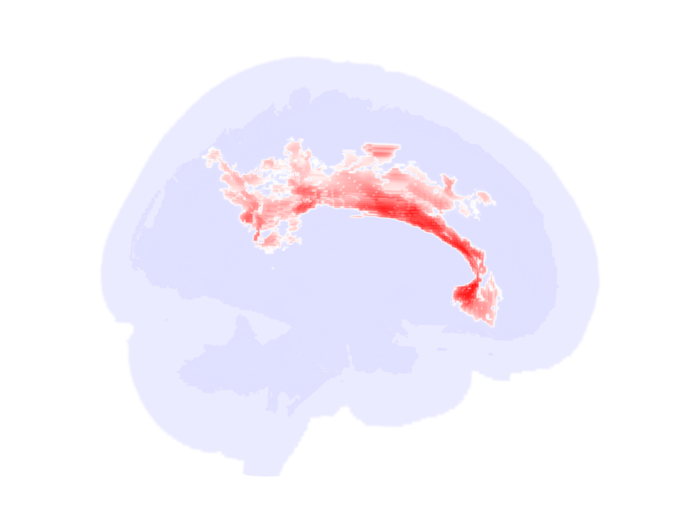

“The aspects of white matter that show a relationship with our early life environment are much more pervasive throughout the brain than we’d thought. Instead of being just one or two tracts that are important for cognition, the whole brain is related to the adversities that someone might experience early in life,” said Carozza.

The team studied data from 9082 children (about half of them girls, with an average age of 9.5) collected in the Adolescent Brain Cognitive Development (ABCD) study. This study, funded by the National Institutes of Health and conducted at 21 centres across the U.S., gathered information on brain activity and structure, cognitive abilities, environment, mood and mental health. The researchers looked at several categories of early environmental factors, including prenatal risk factors, interpersonal adversity, household economic deprivation, neighbourhood adversity, and social resiliency factors.

Carozza and Dhand used diffusion imaging scanning of the brain to measure fractional anisotropy (FA)—a way of estimating the integrity of the white matter connections—and streamline count, an estimate of their strength. They then used a computational model to compare how these features of white matter were related to both childhood environmental factors and current cognitive abilities such as language skills and mental arithmetic.

Their analysis revealed widespread differences in white matter connections throughout the brain depending on the children’s early-life environments. In particular, the researchers found lower quality of white matter connections in parts of the brain tied to mental arithmetic and receptive language. These white matter differences accounted for some of the relationship between adverse life experiences in early childhood and lower cognitive performance in adolescence.

“We are all embedded in an environment, and features of that environment such as our relationships, home life, neighbourhood, or material circumstances can shape how our brains and bodies grow, which in turn affects what we can do with them,” said Carozza. “We should work to make sure that more people can have those stable, healthy home lives that the brain expects, especially in childhood.”

The researchers note that their study is based on observational data, which means they cannot draw strong causal conclusions. Brain imaging was also only available at a single timepoint, offering a snapshot but not allowing researchers to track changes over time. Prospective studies—following children over time and collecting brain imaging information at multiple time points—would be needed to more definitively connect adversity and cognitive performance.

Source: Mass General Brigham