New Discovery Reveals the Spinal Cord’s Role in Bladder Control

Urinary incontinence is a devastating condition, leading to significant adverse impacts on patients’ mental health and quality of life. Disorders of urination are also a key feature of all neurological disorders.

A USC research team has now made major progress in understanding how the human spinal cord triggers the bladder emptying process. The discovery could lead to exciting new therapies to help patients regain control of this essential function.

In the pioneering study, a team from USC Viterbi School of Engineering and Keck School of Medicine of USC has harnessed functional ultrasound imaging to observe real-time changes in blood flow dynamics in the human spinal cord during bladder filling and emptying.

The work was published in Nature Communications and was led by Charles Liu, the USC Neurorestoration Center director at Keck School of Medicine of USC and professor of biomedical engineering at USC Viterbi, and Vasileios Christopoulos, assistant professor at the Alfred E. Mann Department of Biomedical Engineering.

The spinal cord regulates many essential human functions, including autonomic processes like bladder, bowel, and sexual function. These processes can break down when the spinal cord is damaged or degenerated due to injury, disease, stroke, or aging. However, the spinal cord’s small size and intricate bony enclosure have made it notoriously challenging to study directly in humans.

Unlike in the brain, routine clinical care does not involve invasive electrodes and biopsies in the spinal cord due to the obvious risks of paralysis.

Furthermore, fMRI imaging, which comprises most of human functional neuroimaging, does not exist in practical reality for the spinal cord, especially in the thoracic and lumbar regions where much of the critical function localises.

“The spinal cord is a very undiscovered area,” Christopoulos said. “It’s very surprising to me because when I started doing neuroscience, everybody was talking about the brain. And Dr. Liu and I asked, “What about the spinal cord?”

“For many, it was just a cable that transfers information from the brain to the peripheral system. The truth was that we didn’t know how to go there—how to study the spinal cord in action, visualize its dynamics and truly grasp its role in physiological functions.”

Functional ultrasound imaging: A new window into the spinal cord

To overcome these barriers, the USC team employed functional ultrasound imaging (fUSI), an emerging neuroimaging technology that is minimally invasive. The fUSI process allowed the team to measure where changes in blood volume occur on the spinal cord during the cycle of urination.

However, fUSI requires a “window” through the bone to image the spinal cord. The researchers found a unique opportunity by working with a group of patients undergoing standard-of-care epidural spinal cord stimulation surgery for chronic low back pain.

“During the implantation of the spinal cord stimulator, the window we create in the bone through which we insert the leads gives us a perfect and safe opportunity to image the spinal cord using fUSI with no risk or discomfort to the study volunteers,” said co-first author Darrin Lee, associate director of the USC Neurorestoration Center, who performed the surgeries.

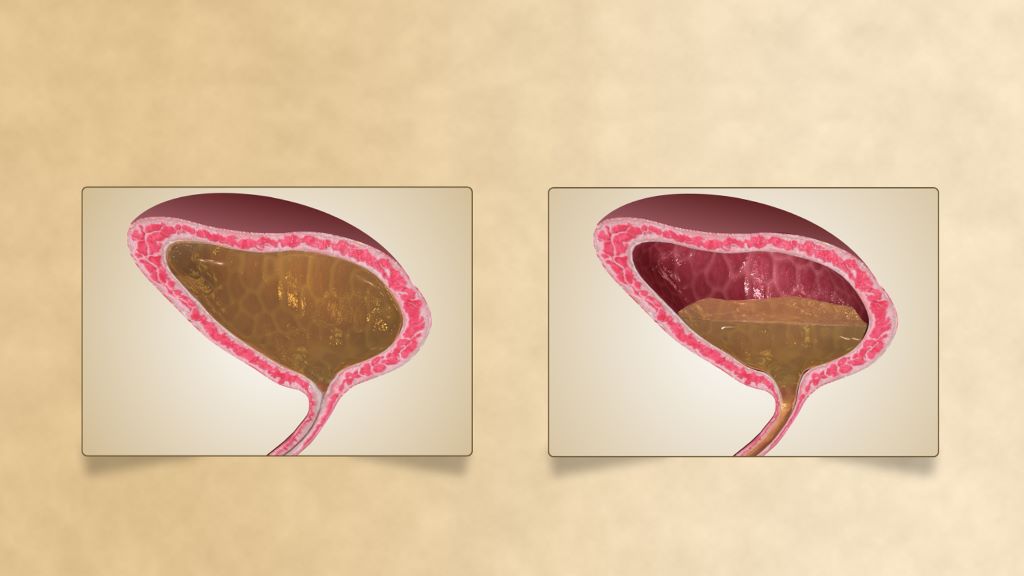

“While the surgical team was preparing the stimulator, we gently filled and emptied the bladder with saline to simulate a full urination cycle under anaesthesia while the research team gathered the fUSI data,” added Evgeniy Kreydin from the Rancho Los Amigos National Rehabilitation Center and the USC Institute of Urology, who was already working closely with Liu to study the brain of stroke patients during micturition using fMRI.

“This is the first study where we’ve shown that there are areas in the spinal cord where activity is correlated with the pressure inside the bladder,” Christopoulos said.

“Nobody had ever shown a network in the spinal cord correlated with bladder pressure. What this means is I can look at the activity of your spinal cord in these specific areas and tell you your stage of the bladder cycle – how full your bladder is and whether you’re about to urinate.”

Christopoulos said the experiments identified that some spinal cord regions showed positive correlation, meaning their activity increased as bladder pressure rose, while others showed negative (anti-correlation), with activity decreasing as pressure increased. This suggests the involvement of both excitatory and inhibitory spinal cord networks in bladder control.

“It was extremely exciting to take data straight from the fUSI scanner in the OR to the lab, where advanced data science techniques quickly revealed results that have never been seen before, even in animal models, let alone in humans,” said co-first author Kofi Agyeman, biomedical engineering postdoc.

New hope for patients

Liu has worked for two decades at the intersection of engineering and medicine to develop transformative strategies to restore function to the nervous system. Christopoulos has spent much of his research career developing neuromodulation techniques to help patients regain motor control.

Together, they noted that for patients, retaining control of the autonomic processes that many of us take for granted is more fundamental than even walking.

“If you ask these patients, the most important function they wanted to restore was not their motor or sensory function. It was things like sexual function and bowel and bladder control,” Christopoulos said, noting that urinary dysfunction often leads to poor mental health. “It’s a very dehumanising problem to deal with.”

Worse still, urinary incontinence leads to more frequent urinary tract infections (UTIs) because patients must often be fitted with a catheter. Due to limited sensory function, they may not be able to feel that they have an infection until it is more severe and has spread to the kidneys, resulting in hospitalisation.

This study offers a tangible path toward addressing this critical need for patients suffering from neurogenic lower urinary tract dysfunction. The ability to decode bladder pressure from spinal cord activity provides proof-of-concept for developing personalised spinal cord interfaces that could warn patients about their bladder state, helping them regain control.

Currently, almost all neuromodulation strategies for disorders of micturition are focused on the lower urinary tract, largely because the neural basis of this critical process remains unclear.

“One has to understand a process before one can rationally improve it,” Liu said.

This latest research marks a significant step forward, opening new avenues for precision medicine interventions that combine invasive and noninvasive neuromodulation with pharmacological therapeutics to make neurorestoration of the genitourinary system a clinical reality for millions worldwide.

Source: University of Southern Carolina