How an SAMRC Study Found that HIV Deaths in SA May be Massively Undercounted

By Chris Bateman

It is widely acknowledged among health and demographic experts that relying solely on what is written on death certificates does not paint an accurate picture of what people in South Africa are actually dying of. Now, an SAMRC study has provided evidence that the undercounting of deaths due to HIV might be even greater than previously thought.

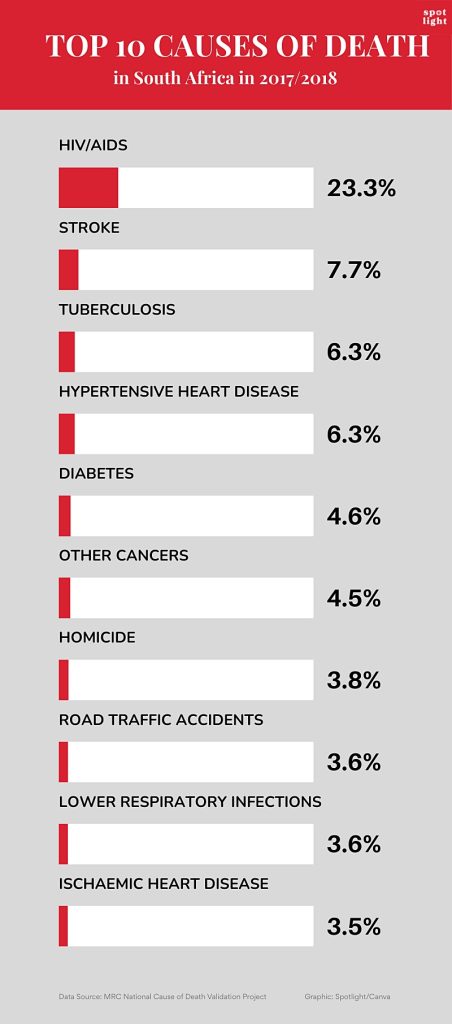

Many in health circles were surprised by a recent South African Medical Research Council (SAMRC) study that found that 23% of deaths in a nationally representative sample drawn from 2017/2018 were due to HIV. By comparison, Stats SA data for roughly the same period puts the figure at only 5.7%.

That Stats SA’s HIV mortality figures differs from other sources is not new and not in itself surprising. This is because Stats SA reports a relatively straight-forward count of what is written on death certificates – where it is known HIV is often not indicated, even if it is the underlying cause of death. By contrast, the new SAMRC study looked at autopsy reports, death certificates, medical records, and interviews with next of kin to come up with its much higher estimate.

The thing that did come as a surprise, is just how much higher the SAMRC figures were than anticipated. Previously, the real number of HIV deaths were thought to be around double the Stats SA number, rather than four times as much. For example, according to Thembisa, the leading model of HIV in South Africa and the basis for UNAIDS’s estimates for the country, around 12% of deaths in the country in 2018 were due to HIV.

“Accurate mortality data are essential for informed public health policies and targeted interventions; however, this study highlights critical gaps in our cause-of-death data, particularly in the underreporting of HIV/AIDS and suicides,” says Professor Debbie Bradshaw, study co-author and Chief Specialist Scientist at the SAMRC Burden of Disease Research Unit, in a media statement. (The study also found substantial under-reporting of suicide on death certificates.)

Multiple data sources

The study was conducted in three phases, examining deaths that were registered in 27 randomly selected health sub-districts between 1 September 2017 and 13 April 2018.

In addition to the examination of autopsy reports, death certificates, and medical records, trained fieldworkers interviewed next of kin to conduct verbal autopsies using a World Health Organization (WHO) questionnaire that had been translated into the country’s nine official languages.

Based on these various sources of data, the cause of each death was categorised into one or more of 44 categories and then compared to the cause of death indicated on the person’s death certificate. (The process for ensuring accuracy, including a review shared by a team of 49 medical doctors, is described in detail in this report.)

The researchers collected data for over 26 000 deaths, although not all types of data were available for each death. Medical records were available for over 17 600 cases, forensic pathology (autopsy) records for 5 700, and about 5 400 verbal autopsies were conducted. In the end, “to save costs”, not all medical records were reviewed.

Overall, for just over 15 000 deaths, the researchers could link and compare their assessment of why a person died to what was written on death certificates.

‘Poor agreement’

The researchers found that “there was poor agreement between the underlying cause of death obtained from the study and the official cause of death data”. The cause of death was the same in only 37% of cases. In addition to the under-reporting of HIV, the researchers also identified “severe under-reporting” of suicide as a cause of death.

A strong link between TB and HIV was observed, with TB responsible for 46% of deaths among people with HIV and 63% of TB deaths occurring in individuals with HIV. Together, these two diseases accounted for almost 30% of deaths.

Some question marks

As noted earlier, the new numbers are substantially higher than estimates from the highly respected Thembisa model. According to their data only 12% of deaths from mid-2017 to mid-2018 were due to HIV-related causes, with a further 9% of deaths occurring in persons with HIV but due to other causes.

Dr Pam Groenewald, a co-author of the new study and also with the SAMRC, describes Thembisa as “an excellent source”. She tells Spotlight they had a long discussion with the Thembisa researchers, “but we weren’t able to fully explain the differences”.

The study authors cite several factors that might contribute to a higher proportion of HIV deaths in their study. Firstly, the weighted national causes of death validation sample aimed to represent the registered deaths in the country, and it was known that deaths in rural areas and child deaths were under-represented. Secondly, deaths that occurred in private sector hospitals were not represented. Groenewald says the HIV-linked deaths in private hospitals are “definitely lower”, but doubts they would have had a significant impact on their findings.

One thing in favour of the study numbers is the fact that the cases they identified with HIV/AIDS as the underlying cause of death were independently reviewed by clinicians. As Groenewald points out, they looked at medical records of people admitted to and who died in hospital, including CD4 cell counts and HIV viral loads. The suggestion is that if someone had a very low CD4 count and a very high HIV viral load at the time of death, then it is very likely HIV played a role in their death, unless of course they died of a clearly non-associated cause like injuries from a car accident.

On the other hand, it might be argued that since HIV is very widely tested for in South Africa, it is more likely to appear on medical records than other less tested for diseases.

Another interesting wrinkle is that the proportion of deaths from HIV/AIDS from this study was higher than anticipated based on observed declines in adult mortality. It is widely accepted that the decline in adult mortality and the increase in life-expectancy over the last two decades was driven by antiretroviral therapy keeping more people with HIV alive. While the new findings do not challenge this narrative, it does suggest the effect may be less pronounced than previously thought.

What to do?

The researchers suggest their study has immediate implications for the country’s response to HIV and TB.

“The study recommends strengthening case finding, follow-up, prevention, and treatment for HIV, AIDS and TB to reduce mortality rates, and underlines the importance of government’s rapid response to counter the recent abrupt withdrawal of Pepfar funding,” Bradshaw comments in the media release.

But more broadly, the findings put the spotlight on major problems in the country’s death certification systems.

“Our findings highlight the need for improved record quality and adherence to testing guidelines within the medical community. Poor record keeping included incomplete documentation of clinical findings and results,” the study authors write.

“A lot of doctors’ report HIV as ‘retroviral disease’, for example, and it’s not coded as HIV,” Groenewald explains to Spotlight.

Urging doctors to record the actual underlying cause of death when writing up death certificates, she also called for improved training in death certification at medical schools.

Doctors’ reluctance to report HIV on death certificates likely has various reasons, including stigma related to HIV and the fact that some medical insurance policies used to exclude HIV, though policies now treat HIV like any other chronic condition.

Overall, Groenewald says, we need to step back and probe the rationale of compiling underlying cause of death statistics.

“The public health aim of the medical certificate of cause of death, (MCCD), is to prevent premature deaths. We therefore need to record the cascade of events or causal sequence of medical conditions leading to death and target our interventions at the underlying cause of death. The coding rules focus on the underlying cause of death, (UCOD), to compile the mortality statistics,” she says.

Groenewald stresses that the law requires doctors to provide accurate information on death causation. The Health Professions Council of SA’s ethical rules also recognised that a statute requiring disclosure about a deceased person’s health must be complied with and is not considered unethical. Contrary to common physician misconception, Groenewald says all this combined to show “it is completely ethical to disclose on a death certificate that a person has died from an AIDS related illness”.

In the meantime, routine mortality data from Stats SA should clearly be taken with a pinch of salt. As Groenewald points out, vital registration data should not be accepted at face value but should be interrogated and cross-checked with other data sources to get coherent and consistent estimates that fit within an envelope of all causes of mortality.

– Additional reporting by Marcus Low.

Republished from Spotlight under a Creative Commons licence.

Read the original article