Immune Ageing Found to Drive – Not Be Driven by – Rheumatoid Arthritis

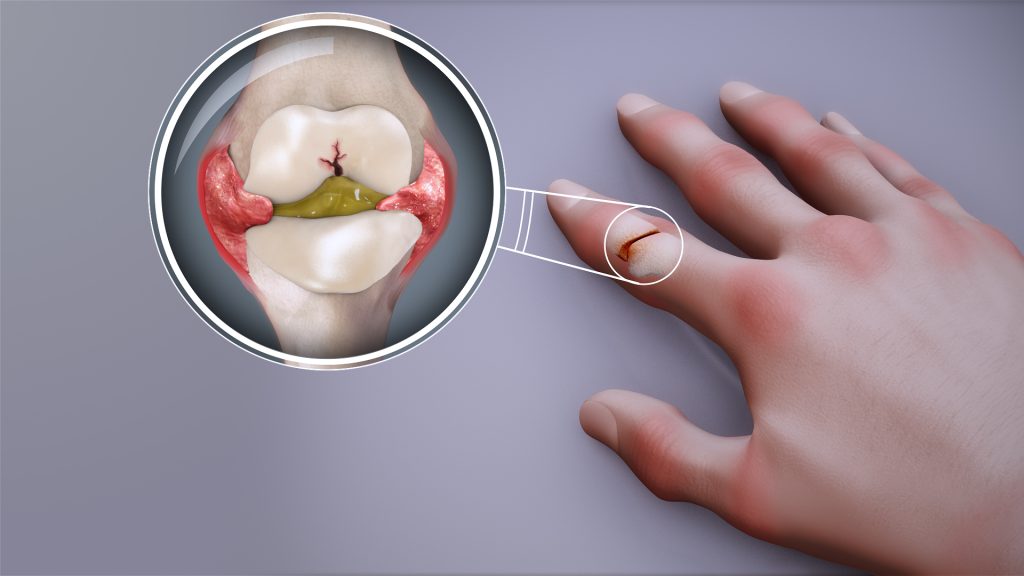

Features of immune system ageing can be detected in the earliest stages of rheumatoid arthritis (RA), even before clinical diagnosis, a new study has found which provides at-risk individuals with hope for early intervention.

The research led by academics at the University of Birmingham, delivered through the National Institute for Health and Care Research (NIHR) Birmingham Biomedical Research Centre, and published in the journal eBioMedicine shows that individuals with joint pain or undifferentiated arthritis already exhibit signs of a prematurely aged immune system, suggesting that immune ageing may play a direct role in the development of RA.

The study involved 224 participants across various stages of RA development and was funded by FOREUM and the European League Against Rheumatism (EULAR). It represents one of the most comprehensive analyses of immune ageing in RA to date.

Researchers found that patients with early immune ageing features were more likely to develop RA. These findings could lead to the development of predictive tools that identify at-risk individuals and enable timely treatment.

“We’ve discovered that immune ageing isn’t just a consequence of rheumatoid arthritis—it may be a driver of the disease itself,” said Dr Niharika Duggal, senior author of the study and Associate Professor in Immune Ageing at the University of Birmingham. “We found that people in the early stages of rheumatoid arthritis ie, before a clinical diagnosis show signs of faster immune system ageing.

“These findings suggest we might be able to intercept the disease development in at-risk individuals and prevent it from developing by using treatments that slow ageing, such as boosting the body’s natural process for clearing out damaged cells (autophagy).”

Key Findings

- Hallmarks of immune ageing, including reduced naïve T cells and thymic output, were observed in patients with early joint symptoms.

- An elevated IMM-AGE score revealed accelerated immune ageing in patients before RA diagnosis.

- Elevated levels of inflammatory markers (such as IL-6, TNFα, and CRP) were found in preclinical stages.

- Advanced ageing features, including senescent T cells and inflammatory Th17 cells, appeared only after RA was fully established.

The study suggests that targeting ageing pathways could offer new strategies to prevent RA. Future research should determine whether geroprotective drugs such as spermidine (autophagy booster), senolytics (clearance of senescent cells) and metformin (attenuates inflammation and boosts autophagy) may help slow or halt disease progression in high-risk individuals.

Source: University of Birmingham