Volcanic Eruptions Set off a Chain of Events that Brought the Black Death to Europe

Clues contained in tree rings have identified mid-14th-century volcanic activity as the first domino to fall in a sequence that led to the devastation of the Black Death in Europe.

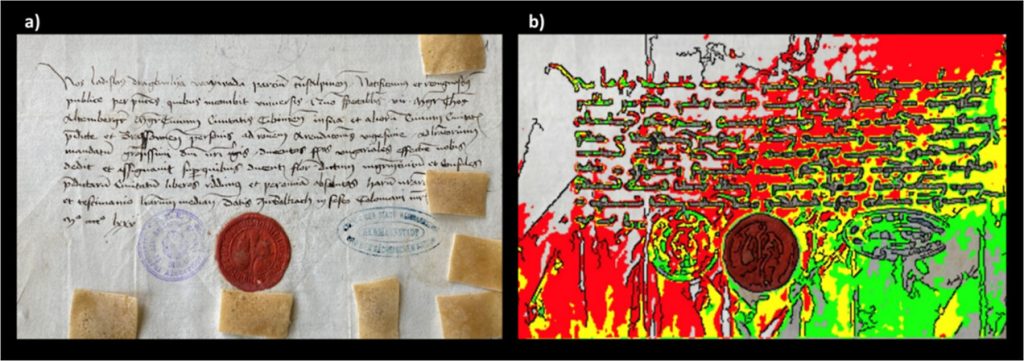

Researchers from the University of Cambridge and the Leibniz Institute for the History and Culture of Eastern Europe (GWZO) in Leipzig have used a combination of climate data and documentary evidence to paint the most complete picture to date of the ‘perfect storm’ that led to the deaths of tens of millions of people, as well as profound demographic, economic, political, cultural and religious change.

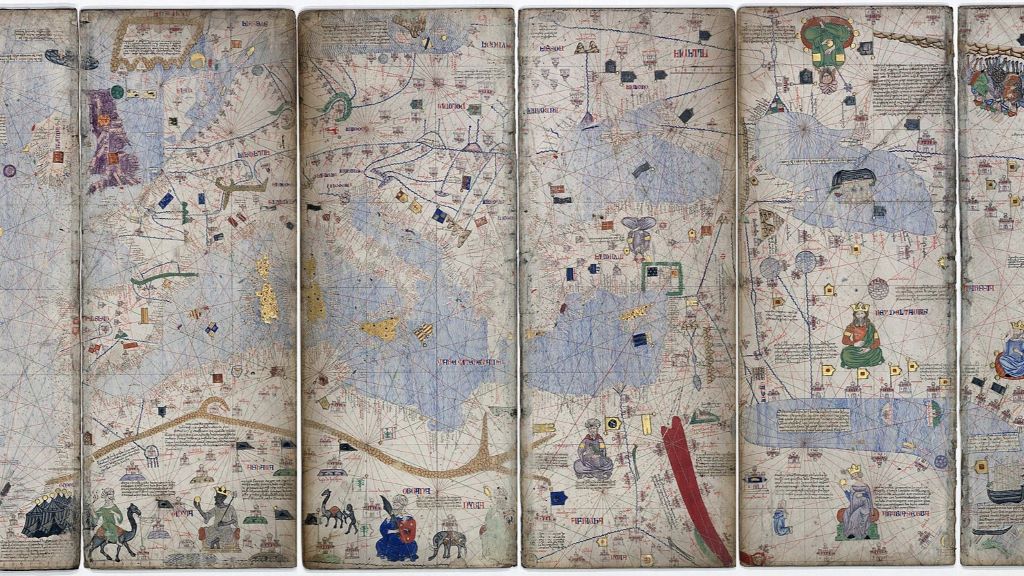

Their evidence suggests that a volcanic eruption – or cluster of eruptions – around 1345 caused annual temperatures to drop for consecutive years due to the haze from volcanic ash and gases, which in turn caused crops to fail across the Mediterranean region. To avoid riots or starvation, Italian city-states used their connections to trade with grain producers around the Black Sea.

This climate-driven change in long-distance trade routes helped avoid famine, but in addition to life-saving food, the ships were carrying the deadly bacterium that ultimately caused the Black Death, enabling the first and deadliest wave of the second plague pandemic to gain a foothold in Europe.

This is the first time that it has been possible to obtain high-quality natural and historical proxy data to draw a direct line between climate, agriculture, trade and the origins of the Black Death. The results are reported in the journal Communications Earth & Environment.

The Black Death was one of the largest disasters in human history. Between 1347 and 1353, it killed millions of people across Europe. In some parts of the continent, the mortality rate was close to 60%.

While it is accepted that the disease was caused by the bacterium Yersinia pestis, which originated from wild rodent populations in central Asia and reached Europe via the Black Sea region, it’s still unclear why the Black Death started precisely when it did, where it did, why it was so deadly, and how it spread so quickly.

“This is something I’ve wanted to understand for a long time,” said Professor Ulf Büntgen from Cambridge’s Department of Geography. “What were the drivers of the onset and transmission of the Black Death, and how unusual were they? Why did it happen at this exact time and place in European history? It’s such an interesting question, but it’s one no one can answer alone.”

Büntgen, whose research group uses information stored in tree rings to reconstruct past climate variability, worked with Dr Martin Bauch, a historian of medieval climate and epidemiology from the Leibniz Institute for the History and Culture of Eastern Europe, on the study.

“We looked into the period before the Black Death with regard to food security systems and recurring famines, which was important to put the situation after 1345 in context,” said Bauch. “We wanted to look at the climate, environmental and economic factors together, so we could more fully understand what triggered the onset of the second plague pandemic in Europe.”

Together, they combined high-resolution climate data and written documentary evidence with conceptual reinterpretations of the connections between humans and climate to show that a volcanic eruption – or series of eruptions – around 1345 was likely the first step in a sequence that ultimately led to the Black Death.

The researchers were able to approximate this eruption through information contained in tree rings from the Spanish Pyrenees, where consecutive ‘Blue Rings’ point to unusually cold and wet summers in 1345, 1346 and 1347 across much of southern Europe. While a single cold year is not uncommon, consecutive cold summers are highly unusual. Documentary evidence from the same period notes unusual cloudiness and dark lunar eclipses, which also suggest volcanic activity.

This volcanically forced climatic downturn led to poor harvests, crop failure and famine. However, the Italian maritime republics of Venice, Genoa and Pisa were able to import grain from the Mongols of the Golden Horde around the Sea of Azov in 1347.

“For more than a century, these powerful Italian city-states had established long-distance trade routes across the Mediterranean and the Black Sea, allowing them to activate a highly efficient system to prevent starvation,” said Bauch. “But ultimately, these would inadvertently lead to a far bigger catastrophe.”

The ships that carried grain from the Black Sea most likely also carried fleas infected with Yersinia pestis, as previous research has already pointed out. But why grain was so urgently needed by the Italians has now become much clearer. It is still unknown exactly where this deadly bacterium originated, but ancient DNA has suggested there may have been a natural reservoir in wild gerbils somewhere in central Asia.

Once the plague-infected fleas arrived in 14th-century Mediterranean ports on grain ships, they became a vector for disease transmission, enabling the bacterium to jump from mammalian hosts – mostly rodents, but potentially including domesticated animals – to humans. It rapidly spread across Europe, devastating the population.

“In so many European towns and cities, you can find some evidence of the Black Death, almost 800 years later,” said Büntgen. “Here in Cambridge, for instance, Corpus Christi College was founded by townspeople after the plague devastated the local community. There are similar examples across much of the continent.”

“And yet, we could also demonstrate that many Italian cities, even large ones like Milan and Rome, were most probably not affected by the Black Death, apparently because they did not need to import grain after 1345,” said Bauch. “The climate-famine-grain connection has potential for explaining other plague waves.”

The researchers say the ‘perfect storm’ of climate, agricultural, societal and economic factors after 1345 that led to the Black Death can also be considered an early example of the consequences of globalisation.

“Although the coincidence of factors that contributed to the Black Death seems rare, the probability of zoonotic diseases emerging under climate change and translating into pandemics is likely to increase in a globalised world,” said Büntgen. “This is especially relevant given our recent experiences with Covid-19.”

The researchers say that resilience to future pandemics requires a holistic approach to address a wide spectrum of health threats. Modern risk assessments should incorporate knowledge from historical examples of the interactions between climate, disease and society.

The research was supported in part by the European Research Council, the Czech Science Foundation and the Volkswagen Foundation.

Reference:

Martin Bauch and Ulf Büntgen. ‘Climate-driven changes in Mediterranean grain trade mitigated famine but introduced the Black Death to medieval Europe.’ Communications Earth and Environment (2025). DOI: 10.1038/s43247-025-02964-0

Republished from University of Cambridge under a Creative Commons licence

Read the original article.