Experimental Drug Repairs DNA Damage Caused by Disease

Cedars-Sinai scientists have developed an experimental drug that repairs DNA and serves as a prototype for a new class of medications that fix tissue damage caused by heart attack, inflammatory disease or other conditions.

Investigators describe the workings of the drug, called TY1, in a paper published in Science Translational Medicine.

“By probing the mechanisms of stem cell therapy, we discovered a way to heal the body without using stem cells,” said Eduardo Marbán, MD, PhD, executive director of the Smidt Heart Institute at Cedars-Sinai and the study’s senior author. “TY1 is the first exomer – a new class of drugs that address tissue damage in unexpected ways.”

TY1 is a laboratory-made version of an RNA molecule that naturally exists in the body. The research team was able to show that TY1 enhances the action of a gene called TREX1, which helps immune cells clear damaged DNA. In so doing, TY1 repairs damaged tissue.

The development of TY1 has been more than two decades in the making. It started when Marbán’s previous laboratory at Johns Hopkins University developed a technique to isolate progenitor cells from the human heart. Like stem cells, progenitor cells can turn into new healthy tissue, but in a more focused manner than stem cells. Heart progenitor cells promote the regeneration of the heart, for example.

Later, at Marbán’s lab at Cedars-Sinai, Ahmed Ibrahim, PhD, MPH, discovered that these heart progenitor cells send out tiny molecule-filled sacs called exosomes. These sacs are loaded with RNA molecules that help repair and regenerate injured tissue.

Ahmed Ibrahim, PhD, MPH“Exosomes are like envelopes with important information,” said Ibrahim, who is associate professor in the Department of Cardiology in the Smidt Heart Institute and first author of the paper. “We wanted to take apart these coded messages and figure out which molecules were, themselves, therapeutic.”

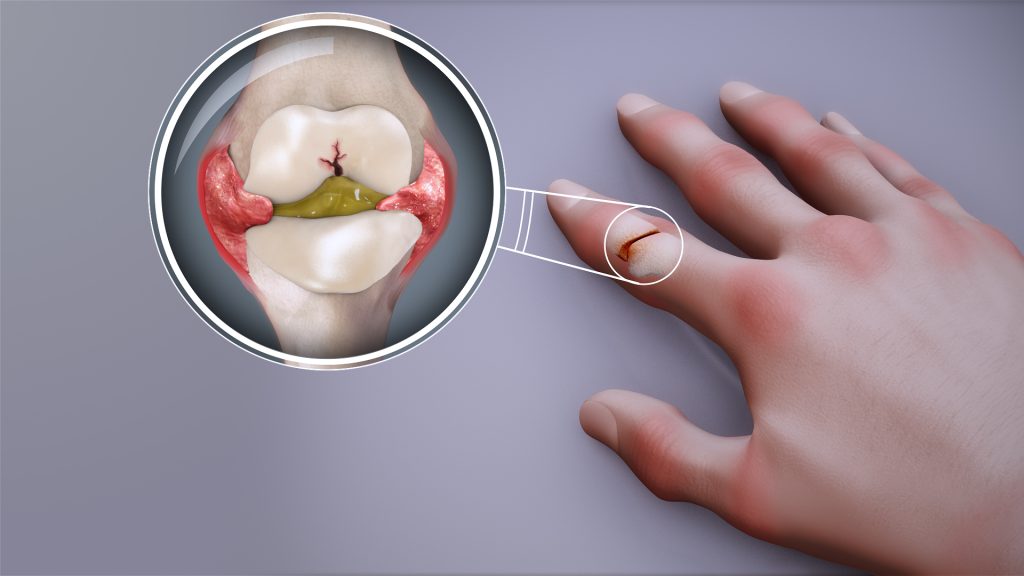

Scientists genetically sequenced the RNA material inside the exosomes. They found that one RNA molecule was more abundant than the others, hinting it might be involved in tissue healing. The investigators found the natural RNA molecule to be effective in promoting healing after heart attacks in laboratory animals. TY1 is the synthetic, engineered version of that RNA molecule, designed to mimic the structure of approved RNA drugs already in the clinic. TY1 works by increasing the production of immune cells that reverse DNA damage, a process that minimises the formation of scar tissue after a heart attack.

“By enhancing DNA repair, we can heal tissue damage that occurs during a heart attack,” Ibrahim said. “We are particularly excited because TY1 also works in other conditions, including autoimmune diseases that cause the body to mistakenly attack healthy tissue. This is an entirely new mechanism for tissue healing, opening up new options for a variety of disorders.”

The investigators next plan to study TY1 in clinical trials.

Source: Cedars–Sinai