Study of 2,800 patients suggests moving beyond chronological cut-offs in cancer care

An international study conducted by the Alliance for Clinical Trials in Oncology and the Acute Myeloid Leukemia Cooperative Group reveals that age-based classifications in the treatment of acute myeloid leukaemia (AML) may be outdated and overly simplistic.

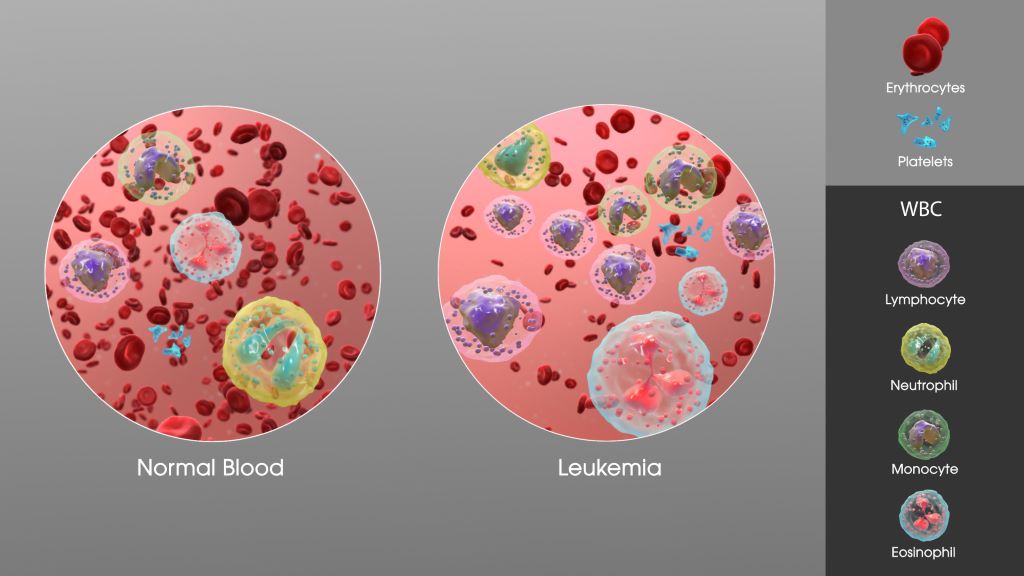

AML is a fast-growing cancer of the blood and bone marrow that disproportionately affects older adults. Historically, age has been a key factor in determining treatment intensity, eligibility for clinical trials, and access to targeted therapies. However, this new research suggests that age alone is not a reliable indicator of disease biology or prognosis.

“Our findings support a more flexible, biology-driven approach to AML treatment and trial design. Age alone should not be a gatekeeper to potentially life-saving therapies,” said Alliance researcher and lead author Ann-Kathrin Eisfeld, MD, associate professor of Internal Medicine and director of the Clara D. Bloomfield Center for Leukemia Outcomes Research at The Ohio State University. “Our results suggest reconsidering age-based eligibility criteria for treatments. By focusing on molecular and genetic profiles rather than chronological age, clinicians may better tailor treatments to individual patients, improving outcomes and expanding access to novel therapies.”

Published in Leukemia, the study analysed data from 2823 adult AML patients treated in the setting of large cooperative group frontline trials across the United States (CALGB/Alliance) and Germany (AMLCG), uncovering nuanced age-related trends in genetic mutations and survival outcomes that challenge current clinical practices. This research is the first large-scale, cross continental study to analyse the mutational patterns and outcomes among patients of all age groups with AML.

The analysis included patients treated with frontline cytarabine-based chemotherapy between 1986 and 2017. Molecular profiling was conducted using targeted sequencing platforms, and survival outcomes were assessed using the 2022 European LeukemiaNet (ELN) genetic-risk classification.

The study found no clear age threshold that could biologically or prognostically separate patients into distinct groups. Instead, genetic mutations and survival outcomes varied continuously across the age spectrum. This challenges the long-standing practice of using arbitrary age cut-offs, such as 60 or 65 years, to guide treatment decisions.

Survival outcomes also declined steadily with age, even among patients classified as having favourable genetic risk. For example, patients aged 18 to 24 with favourable-risk AML had a five-year overall survival rate of 73%, while those aged 75 and older had a survival rate of just 21%. This trend was consistent across all risk categories, indicating that age negatively impacts prognosis regardless of genetic classification.

“This research arrives at a critical moment in oncology, as precision medicine continues to transform cancer care,” added Dr Eisfeld. “Most targeted treatment options are still only available for patients above a certain age threshold that is dictated by corresponding inclusion criteria of pivotal clinical trials, even though patients outside of that age range might equally benefit from these often less toxic treatments.”