Does Hormone Therapy Improve Heart Health in Menopausal Women?

Deciding whether to start hormone therapy during the menopause transition, the life phase that’s the bookend to puberty and when a woman’s menstrual cycle stops, is a hotly debated topic. While hormone therapy is recommended to manage bothersome symptoms like hot flashes and night sweats, Matthew Nudy, assistant professor of medicine at the Penn State College of Medicine, said there’s confusion about the long-term effects of hormone therapy, especially on cardiovascular health.

However, long-term use of oestrogen-based hormone therapies may have beneficial effects on heart health, according to a new study led by Nudy. A multi-institutional team analysed data from hormone therapy clinical trials that were part of the Women’s Health Initiative (WHI), a long-term national study focused on menopausal women, and found that oestrogen-based hormone therapy improved biomarkers associated with cardiovascular health over time. In particular, the study suggests that hormone therapy may lower levels of lipoprotein(a), a genetic risk factor associated with a higher risk of heart attack and stroke.

Their findings were published in the journal Obstetrics & Gynecology.

“The pendulum has been swinging back and forth as to whether hormone therapy is safe for menopausal women, especially from a cardiovascular disease perspective,” Nudy said. “More recently, we’re recognising that hormone therapy is safe in younger menopausal women within 10 years of menopause onset, who are generally healthy and who have no known cardiovascular disease.”

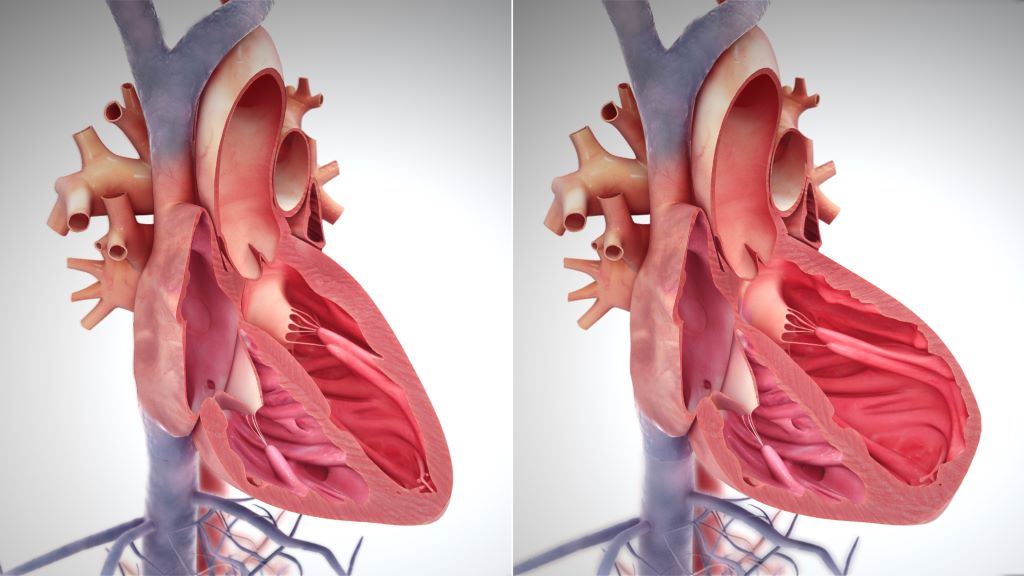

The hormonal changes that accompany menopause come with an increased risk of cardiovascular disease. The decline in the oestrogen can lead to changes in cholesterol, blood pressure and plaque buildup in blood vessels, which increase the risk of heart attack and stroke.

The research team was interested in understanding the long-term effect of hormone therapy on cardiovascular biomarkers, which hasn’t been evaluated over an extended period of time. Prior research in the field primarily looked at short-term effects.

Here, the team analysed biomarkers associated with cardiovascular health over a six-year period from a subset of women who had participated in an oral hormone therapy clinical trial that was part of the WHI. Post-menopausal participants aged 50 to 79 were randomly assigned to one of two groups, an oestrogen-only group and an oestrogen plus progesterone group. They provided blood samples at baseline and at the one-, three- and six-years marks. In total, they analysed samples from 2696 women, approximately 10% of the total trial participants.

The research team found that hormone therapy had a beneficial effect on most biomarkers in both the oestrogen-only and the oestrogen-plus-progesterone groups over time. Levels of LDL cholesterol, the so-called “bad” cholesterol, were reduced by approximately 11% while total cholesterol and insulin resistance decreased in both groups. HDL cholesterol, the so-called “good” cholesterol, increased by 13% and 7% for the oestrogen-only and oestrogen-and-progesterone groups, respectively.

However, triglycerides and coagulation factors, proteins in the blood that help form blood clots, increased.

The decrease in lipoprotein(a) concentration was more pronounced among participants with American Indian or Alaska Native ancestry or Asian or Pacific Islander ancestry, by 41% and 38%, respectively. The reason why was unclear, Nudy said.

More surprising to the research team, they said, levels of lipoprotein(a), a type of cholesterol molecule, decreased 15% and 20% in the oestrogen-only and the oestrogen-plus-progesterone groups, respectively. Unlike other types of cholesterol, which can be influenced by lifestyle and health factors such as diet and smoking, concentrations of lipoprotein(a) are thought to be determined primarily by genetics, Nudy explained. Patients with a high lipoprotein(a) concentration have an increased risk of heart attack and stroke, especially at a younger age. There’s also an increased risk of aortic stenosis, where calcium builds up on a heart valve.

“As a cardiologist, this finding is the most interesting aspect of this research,” Nudy said. “Currently, there are no medications approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to lower lipoprotein(a). Here, we essentially found that oral hormone therapy significantly reduced lipoprotein(a) concentrations over the long-term.”

Nudy noted that the oestrogen therapy the women received in the clinical trial was conjugated equine oestrogens, a commonly prescribed form of oral oestrogen therapy. Before being absorbed by the body, oral hormone therapy is processed in the liver, through a process called first-pass metabolism. That process could increase inflammatory markers, which may explain the rise in triglycerides and coagulation factors.

“There are now other common formulations of oestrogen hormone therapy like transdermal oestrogen, which is administered through the skin,” Nudy said. “Newer studies have found that transdermal oestrogen doesn’t increase triglycerides, coagulation factors or inflammatory markers.”

For those considering menopause hormone therapy, Nudy recommended undergoing a cardiovascular disease risk assessment, even if the person hasn’t had a previous heart attack or stroke or hasn’t been diagnosed with cardiovascular disease. It will give health care providers more information when considering the best option to treat menopause symptoms.

“Currently, hormone therapy is not FDA-approved to reduce the risk of coronary artery disease or stroke,” Nudy said.

Source: Penn State