Placenta Acts to Shield Foetus from Serotonin

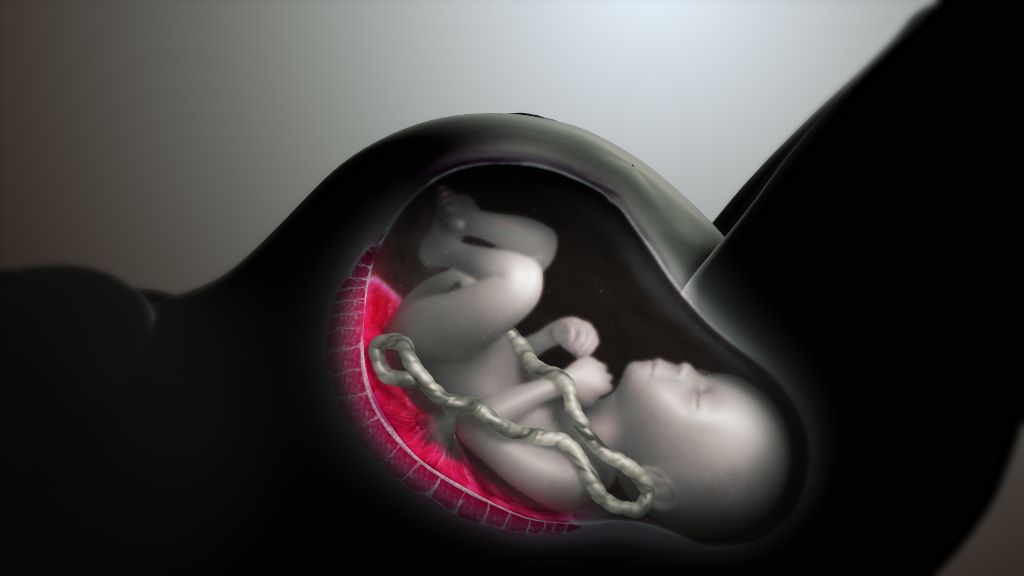

The placenta has long been thought to produce serotonin during pregnancy. But in a new study, Yale researchers shatter the deep-rooted hypothesis – and show that the placenta doesn’t produce serotonin but instead regulates its delivery to the embryo and foetus. They found that serotonin comes from the pregnant parent, with the placenta acting as a “serotonin shield” that controls how much reaches the embryo and foetus.

The findings, published in the journal Endocrinology, could offer critical insights into how a parent’s serotonin levels might affect the development of their baby’s body and brain, the researchers say.

“The placenta is in essence the ‘serotonin shield’ that regulates how much serotonin is ultimately delivered to the embryo and foetus, not the source of serotonin,” said Harvey Kliman, a research scientist in the Department of Obstetrics, Gynecology, and Reproductive Sciences at Yale School of Medicine and corresponding author of the study. “Why does this matter? Because now we correctly know where this delivery is regulated.”

Often called a “happiness hormone,” serotonin regulates mood, so it’s often associated with the brain. In reality, less than 5% of serotonin is made in the brain, with 95% of it made in the gut. But serotonin does more than just regulate mood. It’s also a growth hormone. In the gut, it gets taken up by platelets and is delivered to parts of the body that need to grow, including in wound healing.

During pregnancy, serotonin also helps with growth: It travels into the placenta through a special protein known as the serotonin transporter (SERT) where it plays a critical role in the development of the embryo and foetus.

Serotonin from the mother is taken up by the foetal placenta, which then produces a myriad of hormones, growth factors, and regulators that are delivered to the foetus.

For the new study, researchers sought to better understand these relationships by using a pure source of placenta cells, unlike in previous studies that looked at either whole animals or isolated mouse placentas. To do so, they first purified human cytotrophoblasts, which are the stem cells that make all the cells of the placenta. They then added serotonin to those cells to see where it would go and discovered it concentrated in the nucleus. Next, they used a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) that blocked SERT, escitalopram, to show that the normal growth, function, and differentiation of these cells was completely blocked.

They also used another inhibitor called cystamine to block serotonylation, or the process by which serotonin is added to proteins like histone 3, which turns genes “on” and “off.” Again, that completely blocked the normal growth of the cells.

Blocking either SERT or serotonylation led to significant changes in gene expression of RNAs in the cytotrophoblasts, they found. Some genes, including ones involved in making, moving, and growing cells, became downregulated, or less active, when serotonin couldn’t enter the cell. Other gene, including ones that help cells stay alive and protect them, became upregulated, or more active. According to the researchers, these findings show that serotonin is critical for the growth of the cytotrophoblasts, the placenta, and by extension, the foetus.

Additionally, researchers discovered that the cytotrophoblasts don’t contain tryptophan hydroxylase (TPH-1), or the enzyme that makes serotonin, indicating the cells within the placenta can’t produce serotonin on their own.

“This suggests that factors that either inhibit serotonin transport through the placenta, or increase it, may have a significant impact on the placenta, embryo, foetus, and ultimately, the newborn and its brain,” Kliman said.

For example, Kliman says this explains why taking SSRIs, which decrease the levels of serotonin into the placenta, leads to smaller babies, and why, conversely, increased levels of serotonin may lead to bigger babies, with bigger brains, who may be at increased risk for developmental disabilities like autism.

Kliman and his lab have long investigated the link between placentas and children with autism, specifically the number of trophoblast inclusions (TIs) in the placenta. TIs are like wrinkles or folds in the placenta, caused by cells multiplying more than they should, typically only seen in pregnancies where there are genetic problems with the foetus.

This new study is the culmination of research first published in 2006 that found significantly more TIs in the placentas from children with autism, and later in 2021, that the genetics of the foetus, and not the parent’s uterine environment, determine how many TIs are in the placenta.

“This puts a big nail into the theory that vaccines cause autism,” suggested Kliman. “Autism, in essence, starts in the womb, not after delivery, and is most likely due to the genetics of the placenta and to a lesser extent, the maternal environment the placenta finds itself in.”

Source: Yale News