Decoding Baby Eczema and Reassurance for Parents

For many South African parents, few things are more stressful than watching their baby’s delicate skin flare up with redness, dryness, or tiny itchy patches. Baby eczema, also called atopic dermatitis, affects up to 1 in 5 children worldwide – and while it’s common, it can leave parents feeling worried and overwhelmed.

But the good news is, with the right skincare routine, baby eczema is manageable. And no, it doesn’t mean your little one will always struggle with sensitive skin.

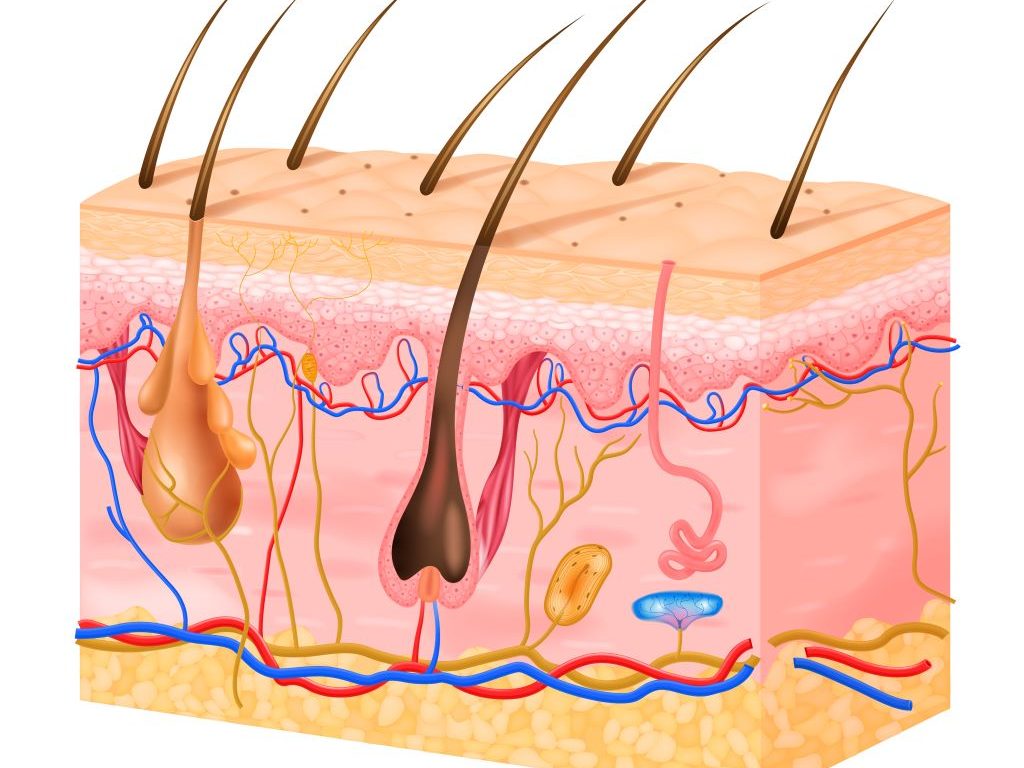

“Parents are often surprised to learn that baby eczema is not a sign that they’re doing something wrong,” says Karen Van Rensburg, spokesperson for Sanosan South Africa. “It’s a common skin condition linked to an underdeveloped skin barrier, and the key is to protect and strengthen that barrier with gentle care.”

Baby eczema usually shows up between two and six months of age. It can appear on the face, behind the ears, on the arms, legs, or even the chest. The skin becomes dry, red, itchy and, in some cases, scaly.

“Triggers vary,” explains Van Rensburg. “It could be heat, dry air, soaps with harsh ingredients, or even certain fabrics. Understanding what sparks your baby’s flare-ups is an important step in managing the condition.”

So what can parents do at home? Here are some dermatologist-approved tips:

1. Keep baths short and sweet

Stick to lukewarm water and limit bath time to 5–10 minutes. Avoid bubble baths and fragranced soaps.

2. Moisturise immediately after bathing

Lock in hydration by applying a fragrance-free, gentle moisturiser while your baby’s skin is still slightly damp.

3. Choose your products wisely

Opt for creams specifically designed for sensitive baby skin. Look for formulas enriched with natural oils, chamomile, or panthenol – like those found in Sanosan’s baby skincare range.

4. Watch the wardrobe

Dress your baby in soft, breathable cotton and avoid scratchy fabrics like wool. Always wash new clothes before wearing.

5. Spot and soothe flare-ups early

At the first sign of redness or irritation, apply a gentle, protective cream to calm the skin.

6. Don’t overheat the room

Babies with eczema are often sensitive to heat. Keep the nursery cool and use a humidifier if the air feels very dry.

7. See a healthcare professional when needed

If the rash is severe, infected, or your baby seems very uncomfortable, always seek medical advice.

“Parents sometimes think stronger products will ‘fix’ eczema faster,” says Van Rensburg. “But baby skin is incredibly delicate. Harsh ingredients strip away natural oils and make things worse. Gentle, consistent care is far more effective in the long run.”

Baby eczema can feel daunting, but with the right care and patience, most little ones outgrow it as their skin barrier matures. In the meantime, gentle skincare, lots of cuddles, and a watchful eye on triggers can make the world of difference.

“Think of it as supporting your baby’s skin while it learns to protect itself,” Van Rensburg adds. “You’re not just treating eczema – you’re helping build a healthy foundation for life.”

Sanosan focuses on natural ingredients and gentle formulas for healthy skin. Using active ingredients specially tailored to your baby’s skin, natural milk protein is the central ingredient in Sanosan and is especially nourishing. More than 90 % of the ingredients are of natural origin such as organic olive oil, and the formulations are biodegradable.

Safety first: all products are clinically tested and are free from parabens, silicones, paraffins, SLS / SLES and phenoxyethanol. For more info visit sanosan.co.za