Men’s Heart Attack Risk Climbs by Mid-30s, Years Before Women

Decades-long US study suggests prevention and screening should start earlier in adulthood

The findings, based on more than three decades of patient follow-up, suggest that heart disease

Men begin developing coronary heart disease — which can lead to heart attacks — years earlier than women, with differences emerging as early as the mid-30s, according to a large, long-term study led by Northwestern Medicine.

The findings, based on more than three decades of patient follow-up, suggest that heart disease prevention and screening should start earlier in adulthood, particularly for men.

“That timing may seem early, but heart disease develops over decades, with early markers detectable in young adulthood,” said study senior author Alexa Freedman, assistant professor of preventive medicine at Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine.

“Screening at an earlier age can help identify risk factors sooner, enabling preventive strategies that reduce long-term risk.”

Older studies have consistently shown that men tend to experience heart disease earlier than women. But over the past several decades, risk factors like smoking, high blood pressure and diabetes have become more similar between the sexes. So, it was surprising to find that the gap hasn’t narrowed, Freedman said.

To better understand why sex differences in heart disease persist, Freedman and her colleagues say it’s important to look beyond standard measures such as cholesterol and blood pressure and consider a broader range of biological and social factors.

Tracking heart disease from young adulthood

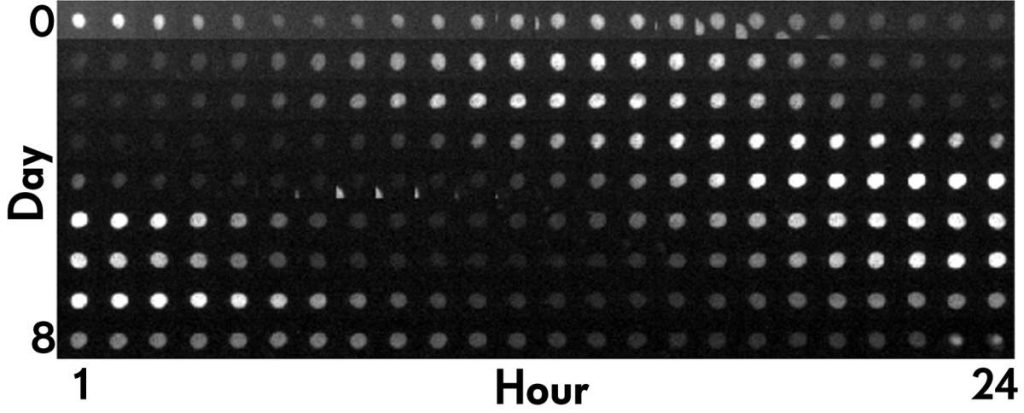

The study analysed data from the Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults (CARDIA) study, which enrolled more than 5100 Black and white adults ages 18 to 30 in the mid-1980s and followed them through 2020.

Because participants were healthy young adults at enrollment, the scientists were able to pinpoint when cardiovascular disease risk first began to diverge between men and women. Men reached 5% incidence of cardiovascular disease (defined broadly to include heart attack, stroke and heart failure) about seven years earlier than women (50.5 versus 57.5 years).

The difference was driven largely by coronary heart disease. Men reached a 2% incidence of coronary heart disease more than a decade earlier than women, while rates of stroke were similar and differences in heart failure emerged later in life. “This was still a relatively young sample – everyone was under 65 at last follow-up – and stroke and heart failure tend to develop later in life,” Freedman explained.

Beyond traditional risk factors

The scientists examined whether differences in blood pressure, cholesterol, blood sugar, smoking, diet, physical activity and body weight could explain the earlier onset of heart disease in men. While some factors, particularly hypertension, explained part of the gap, overall cardiovascular health did not fully account for the difference, suggesting other biological or social factors may be involved.

A critical age: 35

One of the most striking findings was when the risk gap opened. The scientists found that men and women had similar cardiovascular risk through their early 30s. Around age 35, however, men’s risk began to rise faster and stayed higher through midlife. Heart disease screening and prevention efforts often focus on adults over 40. The new findings suggest that approach may miss an important window.

The authors highlight the relatively new American Heart Association’s PREVENT risk equations, which can predict heart disease starting at age 30, as a promising tool for earlier intervention.

Source: Northwestern University