Brain Stimulation and Mindfulness Exercises Could Reduce ‘Latchkey Incontinence’

Arriving home after a long day may be a relief, but for some people, seeing their front door or inserting a key into the lock triggers a powerful urge to pee. Known as “latchkey incontinence,” this phenomenon is the subject of a new study by researchers at the University of Pittsburgh who found that mindfulness training and/or non-invasive brain stimulation could reduce bladder leaks and feelings of urgency evoked by these cues.

The findings of the pilot study, the first evaluation of brain-based therapies for urinary incontinence, are published in the latest issue of the journal Continence.

“Incontinence is a massive deal,” said senior author Dr. Becky Clarkson, research assistant professor in the Pitt School of Medicine Division of Geriatrics and co-director of the Continence Research Center. “Bladder leaks can be really traumatizing. People often feel like they can’t go out and socialise or exercise because they’re worried about having an accident. Especially for older adults, this feeds into social isolation, depression and functional decline. Our research aims to empower people with tools to get back their quality of life.”

Latchkey incontinence, or situational urgency urinary incontinence, is bladder leakage triggered by specific environments or scenarios. Common cues include one’s front or garage door, running water, getting into a car or walking past public restrooms.

According to lead author Dr. Cynthia Conklin, associate professor in the Pitt Department of Psychiatry, latchkey incontinence is a type of Pavlovian conditioning. Like Pavlov’s dogs, which salivated upon hearing a bell that they associated with food, years of going to the bathroom immediately upon entering the house can condition one to feel strong bladder urgency when seeing the front door.

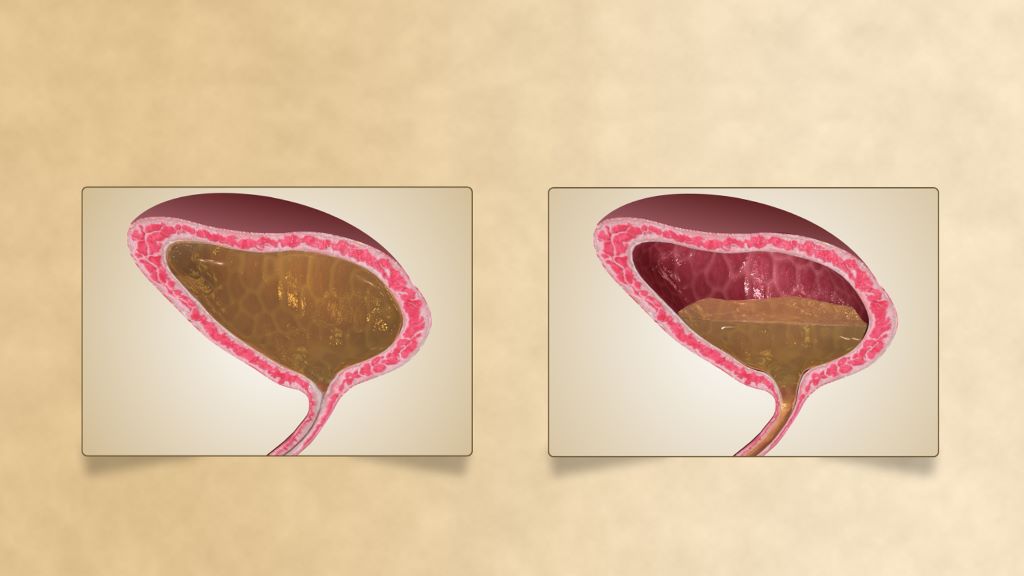

In a previous study, Clarkson and Conklin showed participants pictures of their own front doors or other triggers versus “safe” images of things that did not evoke urgency while they had an MRI of their brain. A part of the brain called the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex was more active when participants viewed urgency-related images.

“The prefrontal cortex is the seat of cognitive control,” said Clarkson. “It’s the executive function center of the bladder, the bit that is telling you, ‘Okay, it’s time to go. You should find somewhere to go.’”

The researchers hypothesised that activating this part of the brain during exposure to urgency cues, through mindfulness and/or with transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS) of the brain, could improve participants’ ability to regulate responses to these cues and control urgency and leakage.

They recruited 61 women aged over 40 who reported regular situationally triggered bladder leaks and randomly assigned them to one of three groups: Participants either listened to a 20-minute mindfulness exercise, received tDCS or both while viewing personal trigger photos.

The mindfulness exercise, developed by coauthor Dr Carol Greco, associate professor of psychiatry and physical therapy at Pitt, was like a typical body scan practice that instructs participants to move through their body, bringing attention to each part in turn. But unlike most body scans, it included specific acknowledgment of bladder sensation.

After completing four in-office sessions over five to six days, participants in all three groups experienced reduced urgency when they viewed trigger cues. Women in all three groups also reported an improvement in the number of urgency episodes and leaks after completing the sessions.

Although this pilot study did not have a control group, for comparison, the researchers say that the magnitude of improvement from tDCS and mindfulness was similar to what other research has reported for interventions such as medications and pelvic floor therapy.

“Although we need to do more research, these results are really encouraging because they suggest that a behavioral tool like mindfulness can be an alternative or additional way to improve symptoms,” said Conklin. “Balancing multiple prescriptions is a big issue among older adults, and a lot of people are reluctant to take another medication, so I think that’s one of the reasons that we saw such high acceptability of non-pharmacologic interventions in this study.”

More than 90% of recruited participants completed the study.

“Participants loved it,” said Clarkson. “Almost everyone who started the study finished it, even though coming into the office four days within one week was quite a big commitment. We got really great feedback, and a lot of women told us that they continue to use the mindfulness exercise in their daily lives.”

“For the first time in 20 years of doing research, we got thank you cards!” added Conklin. “I think that incontinence is such a taboo subject, and a lot of people find it difficult to talk about, so they often don’t even realize that there are treatments out there. But you don’t have to suffer in silence.”

Now, the researchers are planning to explore whether the mindfulness component of the study could be helpful in independent living facilities to reach a wide range of older adults. They also hope to eventually develop an app-based tool for smartphones.

Source: University of Pittsburgh