First-of-its-kind Technology Helps Man with ALS ‘Speak’ in Real Time

Researchers at the University of California, Davis, have developed an investigational brain-computer interface that holds promise for restoring the ability to hold real-time conversations to people who have lost the ability to speak due to neurological conditions.

In a new study published in the scientific journal Nature, the researchers demonstrate how this new technology can instantaneously translate brain activity into voice as a person tries to speak – effectively creating a digital vocal tract with no detectable delay.

The system allowed the study participant, who has amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), to “speak” through a computer with his family in real time, change his intonation and “sing” simple melodies.

“Translating neural activity into text, which is how our previous speech brain-computer interface works, is akin to text messaging. It’s a big improvement compared to standard assistive technologies, but it still leads to delayed conversation. By comparison, this new real-time voice synthesis is more like a voice call,” said Sergey Stavisky, senior author of the paper and an assistant professor in the UC Davis Department of Neurological Surgery. Stavisky co-directs the UC Davis Neuroprosthetics Lab.

“With instantaneous voice synthesis, neuroprosthesis users will be able to be more included in a conversation. For example, they can interrupt, and people are less likely to interrupt them accidentally,” Stavisky said.

Decoding brain signals at heart of new technology

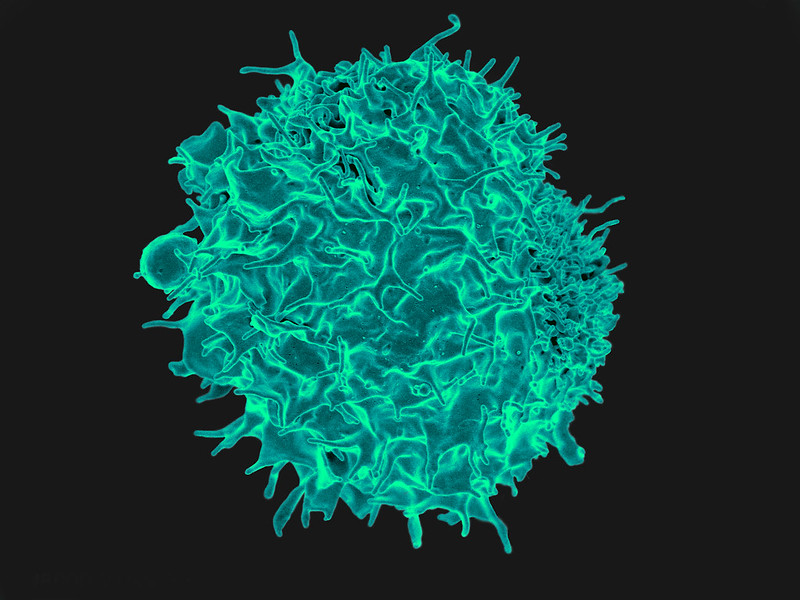

The man is enrolled in the BrainGate2 clinical trial at UC Davis Health. His ability to communicate through a computer has been made possible with an investigational brain-computer interface (BCI). It consists of four microelectrode arrays surgically implanted into the region of the brain responsible for producing speech.

These devices record the activity of neurons in the brain and send it to computers that interpret the signals to reconstruct voice.

“The main barrier to synthesising voice in real-time was not knowing exactly when and how the person with speech loss is trying to speak,” said Maitreyee Wairagkar, first author of the study and project scientist in the Neuroprosthetics Lab at UC Davis. “Our algorithms map neural activity to intended sounds at each moment of time. This makes it possible to synthesise nuances in speech and give the participant control over the cadence of his BCI-voice.”

Instantaneous, expressive speech with BCI shows promise

The brain-computer interface was able to translate the study participant’s neural signals into audible speech played through a speaker very quickly – one-fortieth of a second. This short delay is similar to the delay a person experiences when they speak and hear the sound of their own voice.

The technology also allowed the participant to say new words (words not already known to the system) and to make interjections. He was able to modulate the intonation of his generated computer voice to ask a question or emphasize specific words in a sentence.

The participant also took steps toward varying pitch by singing simple, short melodies.

His BCI-synthesized voice was often intelligible: Listeners could understand almost 60% of the synthesized words correctly (as opposed to 4% when he was not using the BCI).

Real-time speech helped by algorithms

The process of instantaneously translating brain activity into synthesized speech is helped by advanced artificial intelligence algorithms.

The algorithms for the new system were trained with data collected while the participant was asked to try to speak sentences shown to him on a computer screen. This gave the researchers information about what he was trying to say.

The electrodes measured the firing patterns of hundreds of neurons. The researchers aligned those patterns with the speech sounds the participant was trying to produce at that moment in time. This helped the algorithm learn to accurately reconstruct the participant’s voice from just his neural signals.

Clinical trial offers hope

“Our voice is part of what makes us who we are. Losing the ability to speak is devastating for people living with neurological conditions,” said David Brandman, co-director of the UC Davis Neuroprosthetics Lab and the neurosurgeon who performed the participant’s implant.

“The results of this research provide hope for people who want to talk but can’t. We showed how a paralyzed man was empowered to speak with a synthesized version of his voice. This kind of technology could be transformative for people living with paralysis.”

Brandman is an assistant professor in the Department of Neurological Surgery and is the site-responsible principal investigator of the BrainGate2 clinical trial.

Limitations

The researchers note that although the findings are promising, brain-to-voice neuroprostheses remain in an early phase. A key limitation is that the research was performed with a single participant with ALS. It will be crucial to replicate these results with more participants, including those who have speech loss from other causes, such as stroke.