Patients with glioblastoma who received MRI-guided focused ultrasound with standard-of-care chemotherapy had a nearly 40% increase in overall survival in a landmark trial of 34 patients led by University of Maryland School of Medicine (UMSOM) researchers. This is the first time researchers have demonstrated a potential survival benefit from using focused ultrasound to open the blood-brain barrier to improve delivery of chemotherapy to the tumour site in brain cancer patients after surgery.

“Our results are very encouraging. Using focused ultrasound to open the blood-brain barrier and deliver chemotherapy could significantly increase patient survival, which other ongoing studies are seeking to confirm and expand,” said study principal investigator Graeme Woodworth, MD, Professor and Chair of Neurosurgery at UMSOM and Neurosurgeon-In-Chief at the University of Maryland Medical Center (UMMC).

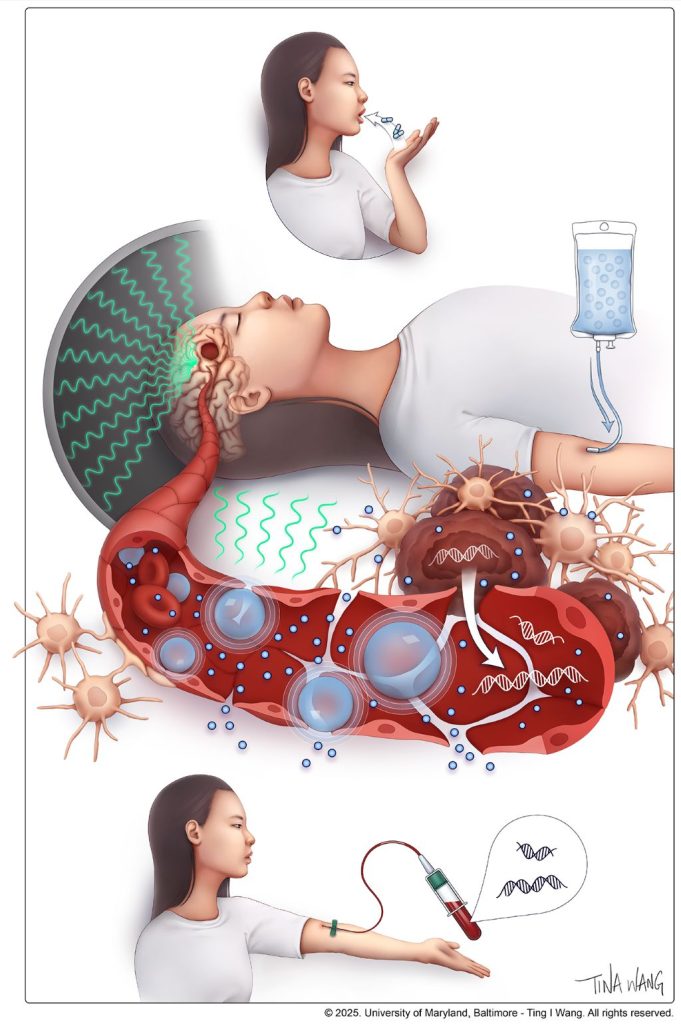

The findings of this groundbreaking safety, feasibility, and comparative trial involved glioblastoma patients who were given focused ultrasound to open their blood-brain barrier before getting chemotherapy; they were matched to a rigorously selected control group of 185 glioblastoma patients with similar characteristics who received the standard dose of the chemotherapy drug, temozolomide, without receiving focused ultrasound. Trial participants were initially treated with surgery to remove their brain tumour, followed by six weeks of chemotherapy and radiation, and up to six monthly focused-ultrasound treatments plus temozolomide.

Results were published in the journal Lancet Oncology and show that trial participants had nearly 14 months of median progression-free survival, compared to eight months in the control group. In terms of overall survival, trial participants, on average, lived for more than 30 months compared to 19 months in the control group.

The study builds on more than a decade of intensive research to test the safety and feasibility of opening the blood-brain barrier using focused ultrasound first in animal studies and then in patients. It was led by Dr Woodworth and was conducted at UMMC and four other university-affiliated clinical sites. “We also demonstrated that this could be a useful technique that enables us to better monitor patients to determine if their brain cancer has progressed,” said Dr Woodworth, who also serves as Director of the Brain Tumor Program at the University of Maryland Marlene and Stewart Greenebaum Comprehensive Cancer Center (UMGCCC).

He and his team demonstrated that opening the blood-brain barrier facilitated the use of a “liquid biopsy,” which is a blood test that detects cancer biomarkers, which can include DNA fragments, proteins and other components from the liquid environment surrounding the tumor site.

Such biomarkers have been used in other cancers to determine whether the tumor has remained stable or has the potential to progress or even metastasize. Up until now, however, these tests have not been utilized in brain cancer patients since most components can never pass into the bloodstream from the brain due to the blood-brain barrier.

“These liquid biomarkers were found to be closely concordant with the patient outcomes over time, progression-free survival and overall survival,” said Dr Woodworth.

While temozolomide is the standard treatment for glioblastoma, the drug typically gets blocked by the blood-brain barrier with studies showing that less than 20 percent reaches the brain in patients. This study did not determine the exact amount of temozolomide to reach the brain in each patient, but earlier studies have shown that opening the blood-brain barrier before delivering chemotherapy can dramatically increase the amount that gets to the original tumor site.

Glioblastoma is the most common and deadliest type of malignant brain tumour. The five-year survival rate is only 5.5%, and patients live an average of 14 to 16 months after diagnosis when treated with surgery, radiation, and chemotherapy when appropriate. The malignancy nearly always recurs even after it is removed due to residual infiltrating cancer cells that remain after treatment.

The blood-brain barrier is a specialized network of vascular and brain cells that acts as the brain’s security system to protect against invasion by dangerous toxins and microbes. It can be opened temporarily using a specialised focused ultrasound device. This process starts with injecting microscopic inert gas-filled bubbles into the patient’s bloodstream. Guided by an MRI, precise brain regions are targeted while the injected microbubbles are circulating.

“Upon excitation under low-intensity ultrasound waves, the microbubbles oscillate within the energy field, causing temporary mechanical perturbations in the walls of the brain blood vessels,” said Pavlos Anastasiadis, PhD, an Assistant Professor of Neurosurgery at UMSOM who is an expert in ultrasound biophysics.

Prior studies led by Dr Woodworth and this trial’s co-investigators showed that opening the blood-brain barrier temporarily can be safely and feasibly performed in brain tumour patients. He and his team conducted this procedure in the first brain cancer patient in the US in 2018 at UMMC after the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved the inaugural clinical trial.

Future trials could use focused ultrasound alongside other chemotherapy agents to test the effectiveness of drugs never used in brain cancer due to their ineffectiveness at crossing the blood-brain barrier.