SA has Very Low Organ Donation Rates – How Can We Fix it?

By Elri Voigt

Thousands of people in South Africa are waiting for a life-saving organ transplant, but our very low organ donation rates mean that many won’t get a transplant in time. Spotlight asks the experts why our donation rates are so low and what can be done about it.

Back in 2002, Rentia le Roux received a horrifying diagnosis that her kidneys were failing. “My kids still need me, they are still small, what are we going to do?” Le Roux recalls telling her doctor. After a long journey trying to manage her kidney failure, she would eventually get a kidney from her sister in 2011.

Le Roux, now the chairperson of the Western Cape Transplant Sports Association, is one of the lucky ones. She spoke to Spotlight ahead of a trip to Germany to take part in the 2025 World Transplant Games.

“There are so many people that are on the list waiting for an organ and the waiting period, it can take many years,” she says.

Incomplete data

While there isn’t a coordinated, centralised database of everyone in South Africa who needs a lifesaving organ transplant, various groups do collect data. This is according to Professor David Thomson, an abdominal transplant surgeon and a critical care sub-specialist. Thomson is also the head of the Transplant Centre of Excellence Project at Groote Schuur Hospital in Cape Town.

“Various entities do collect levels of data, but it’s not very centralised and coordinated, and it could be better…we do have the renal registry that’s trying to track the number of people on dialysis, that’s a good source of information,” Thomson says. The Renal registry is a not-for-profit database that collects and publishes data on dialysis and transplant patients in the country. The database itself is an initiative of the South African Nephrology Society, an NPO that aims to further the field of nephrology and improve patient care.

The society estimates that in 2022, just over 9000 people across the public and private healthcare system were receiving “kidney replacement therapy” – which were either medications to help kidney function, dialysis or a kidney transplant.

A report by the South African Transplant society, an NPO that seeks to advance tissue and organ donation and transplantation, estimated that in 2021, across South Africa’s private and public hospitals, 2 586 people were on a waitlist for a lifesaving organ. Of those, 2382 people were waiting for a kidney, 52 needed a liver, 108 needed a heart transplant, and 44 were waiting for a lung.

But in the same year, the report recorded only 229 transplants done across the country.

South Africa does not have a good organ donation culture, says Professor Mignon McCulloch, the head of paediatric nephrology and solid organ transplant at the Red Cross War Memorial Children’s Hospital. In fact, according to McCulloch, and other experts we spoke to, South Africa has some of the lowest transplantation rates in the world.

While we couldn’t find any straightforward ranking system of organ donation rates, reports by the Global Observatory on Donation and Transplantation (GODT) do provide some insight into how some countries compare to one other. In 2017, according to data from the GODT cited in this 2020 study published in the South African Medical Journal, South Africa had 91 deceased donors, which is a rate of 1.6 per million. By contrast, Spain, which is regarded as having one of the highest rates of organ donation in the world, had 2183 deceased donors, a rate of 47.05 per million.

How it works

Organ donation is broadly classified into living donation and deceased donation.

There are two scenarios where someone can become an organ donor. The first, Thomson explains, is when a healthy person donates an organ without which they can live a normal life, like one of their kidneys. The second is when someone has been declared brain dead and is on a mechanical ventilator or when someone has experienced circulatory death -meaning their heart has stopped beating and “futile non-beneficial treatments have been stopped”. The latter is less common in South Africa.

For deceased donation from a brain-dead patient to take place, the potential donor needs to be in an ICU facility on a mechanical ventilator and referred by their clinical team to a transplant coordinator, says Thomson. If that person is eligible, then the transplant team has to get permission from the next of kin who ultimately have the final say even if the potential donor is registered as an organ donor.

“Organ donation can only happen if someone is on a mechanical ventilator in the end-of-life care pathway, so that is always a complicated and emotional discussion,” he says. “Tissue donations such as corneas, bones, skin, that can happen at the mortuary afterwards and there’s a slightly longer period for when these can be successfully recovered but all donation still requires you to have conversations with and get permission from grieving families.”

Juggling resources

McCulloch describes organ donation as being a bit like “a silent Cinderella”, until someone needs a lifesaving transplant, “and then people suddenly start asking questions about why, why don’t we have more transplantation?”

One reason for this is the allocation of resources and competing priorities within the healthcare system.

Thomson says that organ transplants are a “health intensive resource”, and it’s important to acknowledge that it exists in the context of an already overburdened healthcare system. There is a Deputy Director of dialysis and transplantation within the National Department of Health, Thomson explains, but there isn’t an “overarching central coordinating authority supporting deceased donation”. Instead, he says it is driven by hospital groups and within the provincial healthcare departments by healthcare workers

Adding to this, McCulloch says that doctors are always having to “juggle resources” and if there is only one bed available in an ICU, weighing up whether to give it to someone who will potentially become an organ donor or someone with pneumonia and will likely have a good outcome, is difficult.

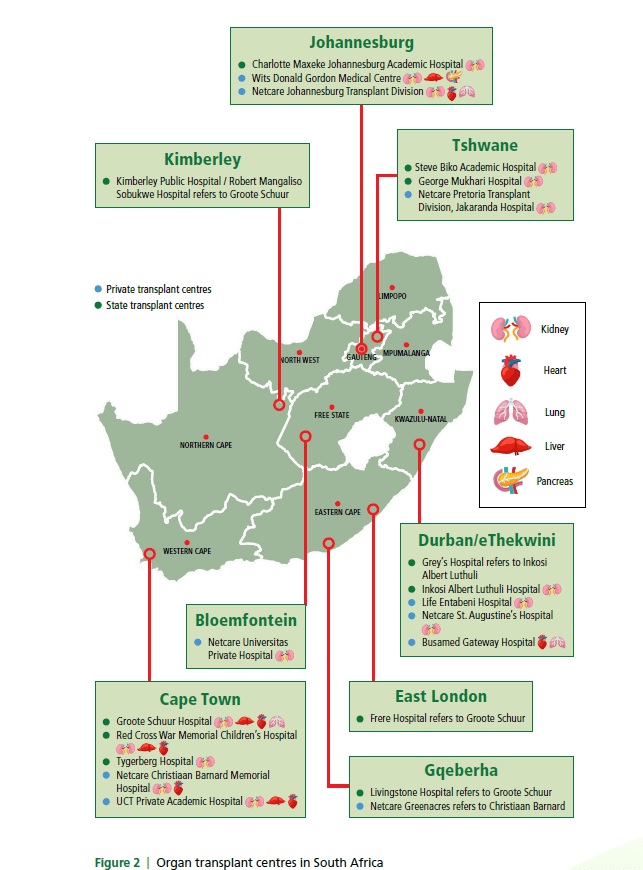

Another challenge is the limited number of surgeons, physicians, and hospitals with the skill and equipment to perform an organ transplant. This strategy roadmap document by the South African Transplant Society list 21 transplants centres across the whole country – 14 of them offer kidney transplants, six offer heart transplants, four offer lung transplants, four offer liver transplants, and only one offers pancreas transplants.

One can save seven

Earlier this year, an unused room in Tygerberg Hospital got a face-lift and a new purpose from a student-run medical non-profit. The initiative called Save7 was kickstarted by a conversation on kidney donation on Stellenbosch University’s Medical Campus. Its initial goal was to raise awareness, particularly among students, that one donor can save up to seven lives. And if tissue like corneas, heart valves, bone and skin are donated, one person can improve the lives of around 50 people.

Jonty Wright, who cofounded Save7, tells Spotlight that the organisation’s founding group of four has now grown to over 200 across multiple universities countrywide. Among others, the group created a Lifepod to solve a transplant-related problem at Tygerberg Hospital. Doctors and staff involved in transplantation at the hospital were citing competing resources as the reason behind low referral rates of potential organ donors by healthcare providers.

The solution posed by Save7, professors on the campus and some of the doctors involved with transplantation was to create a designated bed space for patients who are brain dead and are potential organ donors. The hope was that referrals for potential organ donations would be increased.

The room, Wright says, was an old minor operating theatre and storeroom that belonged to the orthopaedic surgery department and was situated in an ideal spot – in a corridor between the emergency medicine and trauma admissions.

About three months ago, after fundraising efforts and backing by the Health Foundation and other partners, the Lifepod opened. The room currently holds a hospital bed, a ventilator on lease from the surgical department, vitals monitor, cardiac monitor, infusion pumps, emergency trolley, fridge, and crash cart. All the things needed to keep someone who is brain dead’s body comfortable and allow the doctors to counsel their loved ones about potentially donating their organs.

So far, according to Wright, referrals of potential candidates for organ donation at Tygerberg have gone up by 500%, but at the time of the interview none of the next of kin have consented to donating their loved one’s organs. (Data on this has not yet been published).

This ties onto another layer of complexity around organ donation, the reasons why next of kin don’t always give permission.

Need for better education

Samantha Nichols, the executive director of operations for the Organ Donor Foundation, an NGO advocating for organ donations, tells Spotlight that the problem isn’t so much a lack of awareness of organ donation, as a lack of good education around it. She says this affects everyone, including healthcare workers.

Nichols says that “it’s almost like the stars have to align” for a deceased donor to donate their organs, because of how many steps and doctors are involved in the process.

“[W]hen a person is sent to an ICU or trauma unit, the team of doctors that work on that person to save their life is a totally different team to the transplant team,” she says. A transplant team is only ever called in if a potential donor has been declared brain dead by two different doctors who aren’t part of or affiliated with a transplant team.

“[O]nly then can they start the process of talking to the family, and then they still need to get consent from the family before the organs are removed,” she says.

The Opt-in versus Opt-out debate

When it comes to consent for organ donation, South Africa has what is referred to as an opt-in system. An opt-in system means that someone must provide explicit consent of their desire to donate an organ. While an opt-out system means all adults are automatically considered organ donors after death, unless they explicitly withdraw consent beforehand.

There has been some debate about whether switching to opt-out systems would improve organ donation rates. One recent study, in which researchers analysed deceased donor rates in five countries that had switched from an opt-in to an opt-out system, did not find an increase in organ donation rates.

“Unless flanked by investments in healthcare, public awareness campaigns, and efforts to address the concerns of the deceased’s relatives, a shift to an opt-out default is unlikely to increase organ donations,” the researchers concluded.

A 2024 editorial in the Lancet medical journal made a similar point, saying “a simplistic switch to the ‘opt-out’ model is alone not sufficient to boost donation”. Instead, it lists the three components that makes Spain’s transplant programme so successful. “A solid legislative framework, strong clinical leadership, and a highly organised logistics network overseen by the National Transplant Organization.” An opt-out system is also unlikely to work well in South Africa from a legislative perspective, since it might be seen by some to impinge upon an “individual’s rights to personal autonomy and bodily and psychological integrity”, as argued in this article in the Conversation.

The experts Spotlight spoke to instead point to several other changes that could be made to improve donation rates.

‘Everyone can do a bit better’

The responsibility around improving organ transplantation rests on us as society and as a coordinated healthcare system, according to Thomson.

“[E]veryone can do a bit better…and I don’t think you want to make it one person’s responsibility for the performance. It’s actually a collective and how we work together,” Thomson says. “…a lot of things like supporting donation actually links into good palliative care services, and that should be something we’re offering to everyone.”

Thomson advocates for upskilling healthcare workers to be able to better counsel families during end-of-life care, not necessarily just around organ donation but around “engaging humanely with “families and end of life and navigating that complexity with them as the healthcare team”.

He recommends making counselling of grieving families and palliative care discussion a hospital system issue, instead of an individual responsibility by adding it to institutional operating standards. “And then you actually need to audit it, measure it, reflect on it and monitor the outcomes,” he says.

Suhayl Khalfey, a Save7 cofounder, says now that the Lifepod is ready to use, their focus is shifting to educate people about the importance of organ donation. As part of its education efforts, Khalfey says Save7 is putting together a database of different religious leaders to help counsel families uncertain about their faith’s stance on organ donation.

Nichols stresses that transplant teams will honour different religious beliefs and funeral practises and that a donor’s body will not appear disfigured in any way after they’ve donated their organs.

Start by having the conversation

Anyone can register as an organ donor with the Organ Donor Foundation, says Nichols. The process is free and will take less than a minute (see their website here). If a situation arises where you are brain dead and you are a candidate for organ donation your family will still need to give permission.

This is why it is so important to have the conversation with your loved ones about what your wishes are, says Khalfey.

Sachen Naidu, another cofounder of Save7, adds to this saying that often with the students they’ve spoken to, organ donation is viewed as something to think about in the distant future. He encourages young people to reconsider this mindset.

Even children can learn about organ donation.

The non-profit organisation Transplant Education for Living Legacies (TELL) recently launched an educational campaign in South Africa aimed at children in the 5 to 11 age group. The initiative, called the Orgamites Mighty Education Programme, is an international child health education programme originating from Canada. At its heart, the programme is a conversation starter, says Thomson who spoke on a TELL webinar.

“All we want is for people to be having educated conversations about it [organ donations],” he says. “Children need transplants too.”

For McCulloch, organ donation goes beyond impacting just the recipients. She uses the example of families who have lost a child in a tragic accident.

“You had a completely well child five minutes ago and then something terrible happened, and now you’ve got a child who’s died and you’re going to go home with a gap in your heart. Whereas at least when you donate [the] organs to another child, something good can come of out of a really hopeless, tragic situation,” she says.

Thomson adds to this saying: “And that’s a memory that lives with that family for a long time afterwards …not just that time point. That’s what they’re going to remember as part of that event, and it really does offer them a degree of solace for a tragedy.”

And the difference to those receiving organs can obviously be life changing. Receiving a kidney gave Le Roux the chance to see her children grow up. “So, every [milestone] when they wrote matric, when they got their degrees, everything. It’s like a step forward, something I can tick off, I’m still here. I’m able, I’m healthy,” she says.

Republished from Spotlight under a Creative Commons licence.

Read the original article.