Rapid Diagnostics Test Can Detect Asymptomatic Malaria Cases

Researchers have adapted a rapid diagnostic technology that is able to identify undetected cases of malaria, helping tackle the spread of disease.

A team of scientists from Imperial College London, the MRC Unit The Gambia, the Clinical Research Unit of Nanoro in Burkina Faso, ProtonDx Ltd, and the NIHR Global Health Research Group have developed and validated a low-cost, point-of-care diagnostic that can rapidly detect low levels of malaria from a finger prick.

The test, called Dragonfly, relies on technology originally created at Imperial and its spinout ProtonDx. The technology allows users to diagnose malaria with high accuracy, without the need for extensive laboratory equipment or infrastructure. Results can be delivered in as little as 45 minutes, and the test is sensitive enough to detect even the lowest levels of malaria parasites in the blood – meaning that people without symptoms of malaria can still be identified.

Malaria is one of the leading causes of preventable deaths worldwide, with around 95% of all deaths occurring in Africa. Asymptomatic infections are a major driver of ongoing transmission, as individuals who carry the disease without showing symptoms do not seek medical treatment. Mosquitos feeding on blood from people without malaria symptoms can still deliver the malaria parasite to other people when they take their next blood meal. The new technology offers hope for combatting this potential spread of infection, by offering a way to identify previously undetectable malaria cases rapidly and on the ground in countries which are most affected by malaria.

The findings, published in Nature Communications, have significant global health implications as this field-deployable molecular diagnostic method offers a sensitive, scalable solution to support test-and-treat strategies for malaria elimination across Africa.

Professor Aubrey Cunnington, from Imperial’s Department of Infectious Disease and Co-Lead of the NIHR Global Health Research Group with Professor Halidou Tinto (from IRSS, Burkina Faso), said: “This is the first time that a diagnostic test for use outside of a laboratory setting has proven sensitive enough to detect low level malaria parasite infections in people who don’t have any symptoms.

“These people are the main source of malaria transmission, and in countries trying to eliminate malaria, there has long been interest in trying to detect these asymptomatically infected people with a screening test performed in their communities, and then giving treatment to those who are positive.

“Until now, no test has been able to detect enough of these infected people to make this a viable proposition, but the Dragonfly test now makes this possible.”

Detecting the undetectable

By collaboratively working as part of the NIHR Global Health Research Group, scientists were able to develop and test this new technology with the help of researchers in the regions affected most by malaria.

Almost 700 blood samples were collected from the community in The Gambia and Burkina Faso to assess the Dragonfly test’s accuracy against gold standard PCR testing and other common methods of testing, including expert microscopy and rapid diagnostic test (e.g., lateral flow immunoassay).

It was found that the Dragonfly tool could detect >95% of all malaria parasite infections, including 95% detection of those where the numbers of parasites were too low to be detected by looking at blood under a microscope.

Although Dragonfly is currently used as a research-used-only device, important progress is being made to understand the potential cost of a final manufactured version – especially when deployed at scale – a critical factor for effective deployment in sub-Saharan Africa. The team is already working closely with the Africa Centres for Disease Control and Prevention to explore opportunities with local manufacturers in the region, ensuring that production and scale-up can be rooted in local capacity. Future studies will also need to assess the robustness of the tool in community settings which are less connected to laboratory facilities.

Dr Jesus Rodriguez-Manzano, last author and technology development lead, from the Department of Infectious Disease, said “This research would not have been possible without the collaborative nature and all the organisations who took part in this study. The technology delivered through this work represents a game changer for malaria control efforts.”

The testing equipment

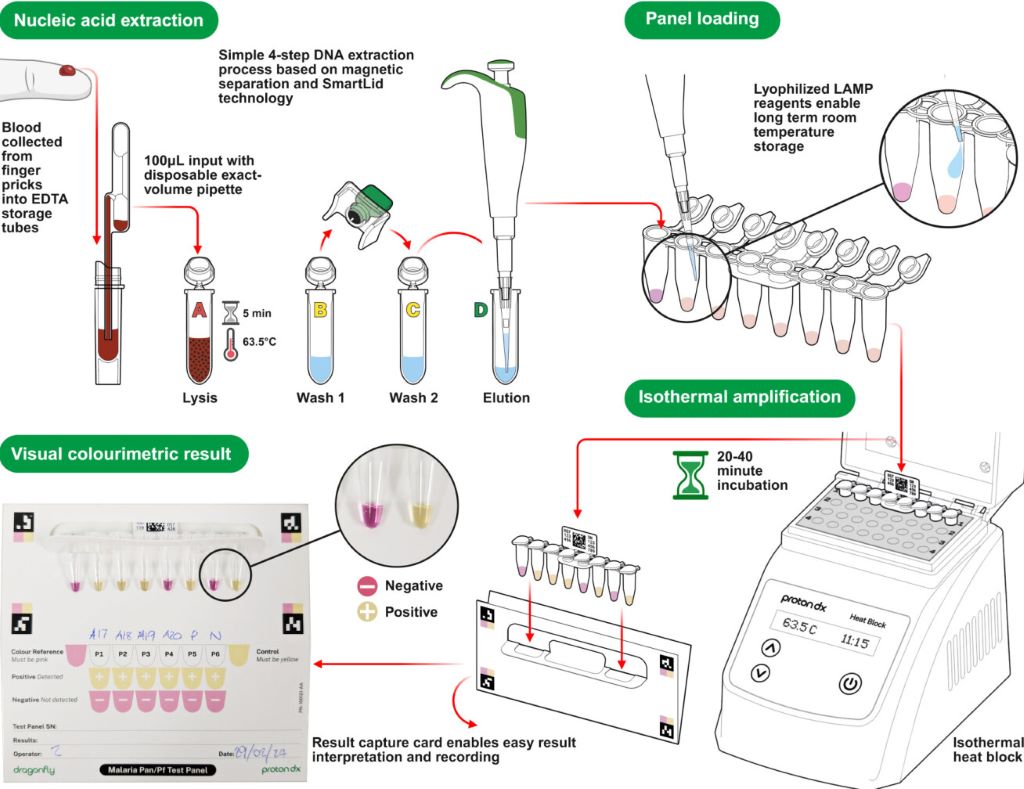

In the Dragonfly testing process, a capillary blood sample obtained from a simple finger prick is processed in around 10 minutes, without the need for specialised laboratory equipment, to extract high-purity nucleic acids from malaria parasites. The prepared sample is then placed into a detection panel, which is inserted into a portable heater.

After a 30-minute incubation at a constant temperature, results can be read visually using a colour chart: a pink reaction indicates a negative result, while a yellow reaction confirms malaria infection.

The Dragonfly can be manufactured at a fraction of the cost of other platforms, is compact enough to fit into a backpack, and can operate on batteries, an important feature for bringing the tool directly to communities without requiring additional specialised equipment. Testing can be carried out by most people without extensive training, meaning that healthcare providers or scientists do not need to be present for its use.

Source: Imperial College London