Controlling Inflammation from Sunburn May Prevent Skin Cancer

In a new study published in Nature Communications, researchers at the University of Chicago have discovered how prolonged exposure to ultraviolet (UV) radiation can trigger inflammation in skin cells through degradation of a key protein called YTHDF2. This protein acts as a gatekeeper in preventing normal skin cells from becoming cancerous. The finding reveals that YTHDF2 plays a crucial role in regulating RNA metabolism to keep cells in a healthy state and opens the door to developing potential new approaches to skin cancer prevention and treatment.

Uncontrolled inflammation triggers skin cancer

Each year, nearly 5.4 million people in the United States are diagnosed with skin cancer, with more than 90% of cases attributed to excessive UV exposure. UV rays can damage DNA and cause oxidative stress and inflammation in skin cells — leading to redness, pain and blistering, commonly known as sunburn.

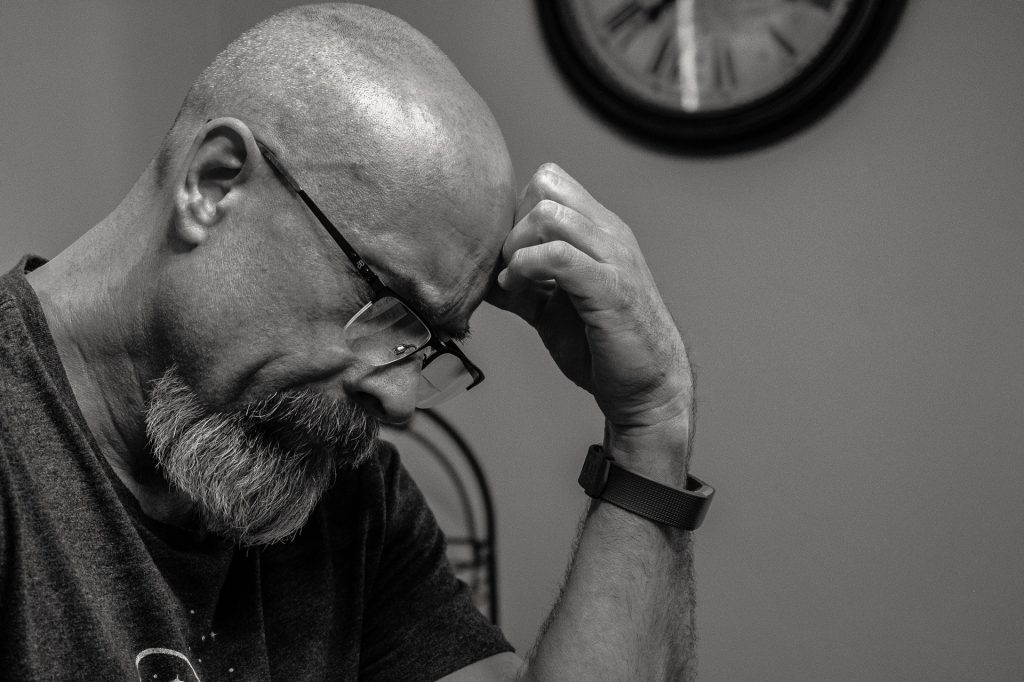

“We’re interested in understanding how inflammation caused by UV exposure contributes to the development of skin cancer,” said Yu-Ying He, PhD, Professor of Medicine in the Section of Dermatology at the University of Chicago.

RNA or ribonucleic acid is an essential molecule that helps convert genetic information into proteins. A special class known as non-coding RNAs regulates gene expression without producing proteins. These molecules typically function in either the nucleus, where a cell’s DNA is stored or the cytoplasm, where most cellular activity occurs.

Low levels of YTHDF2 turn normal skin cells cancerous

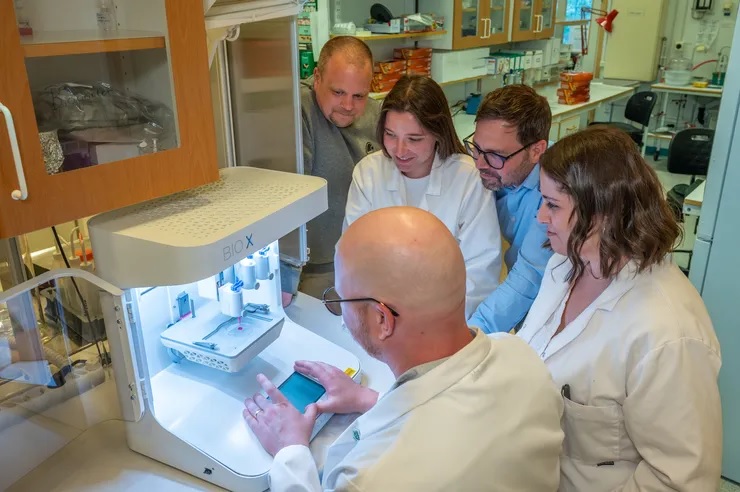

He’s laboratory studies how environmental stressors, such as UV radiation or arsenic in drinking water, affect molecular pathways and damage cellular systems, leading to cancer. Through screening various enzymes, the researchers found that UV exposure causes a marked decrease in levels of YTHDF2, a “reader” protein that specifically binds to RNA sequences marked with a chemical tag known as N6-methyladenosine (m6A).

“When we removed YTHDF2 from skin cells, we saw that UV-triggered inflammation was much worse,” He said. “This suggests that the YTHDF2 protein plays a key role in suppressing inflammatory responses.”

Although inflammation is essential for fighting off infections, it also plays a major role in causing life-threatening diseases, including cancer. However, the molecular mechanisms that regulate this response, especially after UV damage, are not well understood.

YTHDF2 in regulation of non-coding RNA interactions

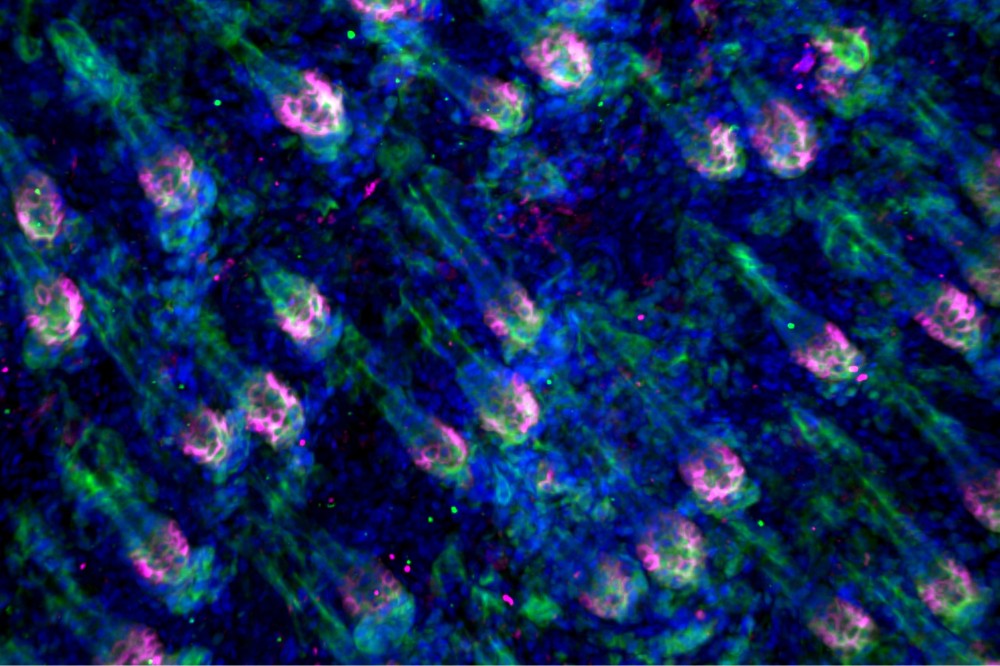

Using multi-omics analysis and additional cellular assays, the research team found that YTHDF2 binds to a specific non-coding RNA known as U6, which is modified by m6A and classified as a small nuclear RNA (snRNA). Under UV stress, cancer cells showed increased levels of U6 snRNA, and these modified RNAs were found to interact with toll-like receptor 3 (TLR3), an immune sensor known to activate inflammatory pathways linked to cancer.

Surprisingly, these interactions occurred within endosomes, where cellular compartments are typically involved in recycling materials, not where U6 snRNA is usually located.

“We spent a lot of time figuring out how these non-coding RNAs get to the endosome, since that’s not where they usually reside,” He explained. “For the first time, we showed that a protein called SDT2 transports U6 into the endosome, and YTHDF2 travels with it.”

Once both YTHDF2 and m6A-modified U6 RNA arrive at the endosome, YTHDF2 blocks the RNA from activating TLR3. However, when YTHDF2 is absent – such as after UV damage, the RNA freely binds to TLR3, triggering harmful inflammation.

“Our study uncovers a new layer of biological regulation, a surveillance system through YTHDF2 that helps protect the body from excessive inflammation and inflammatory damage,” He said.

The findings could open the door to new strategies for preventing or treating UV-induced skin cancer by targeting the RNA-protein interactions that regulate inflammation.

Source: University of Chicago Medicine

The study, “YTHDF2 regulates self non-coding RNA metabolism to control inflammation and tumorigenesis,” was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health, the University of Chicago Medicine Comprehensive Cancer Center, the ChicAgo Center for Health and EnvironmenT (CACHET), and the University of Chicago Friends of Dermatology Endowment Fund.