The brain and spinal cord is made up of billions of neurons connected by synapses and managed and modified by glial cells. When neurons die, this communication network is disrupted and since this loss is irreversible, neuron death causes sensory loss, motor impairment and cognitive decline.

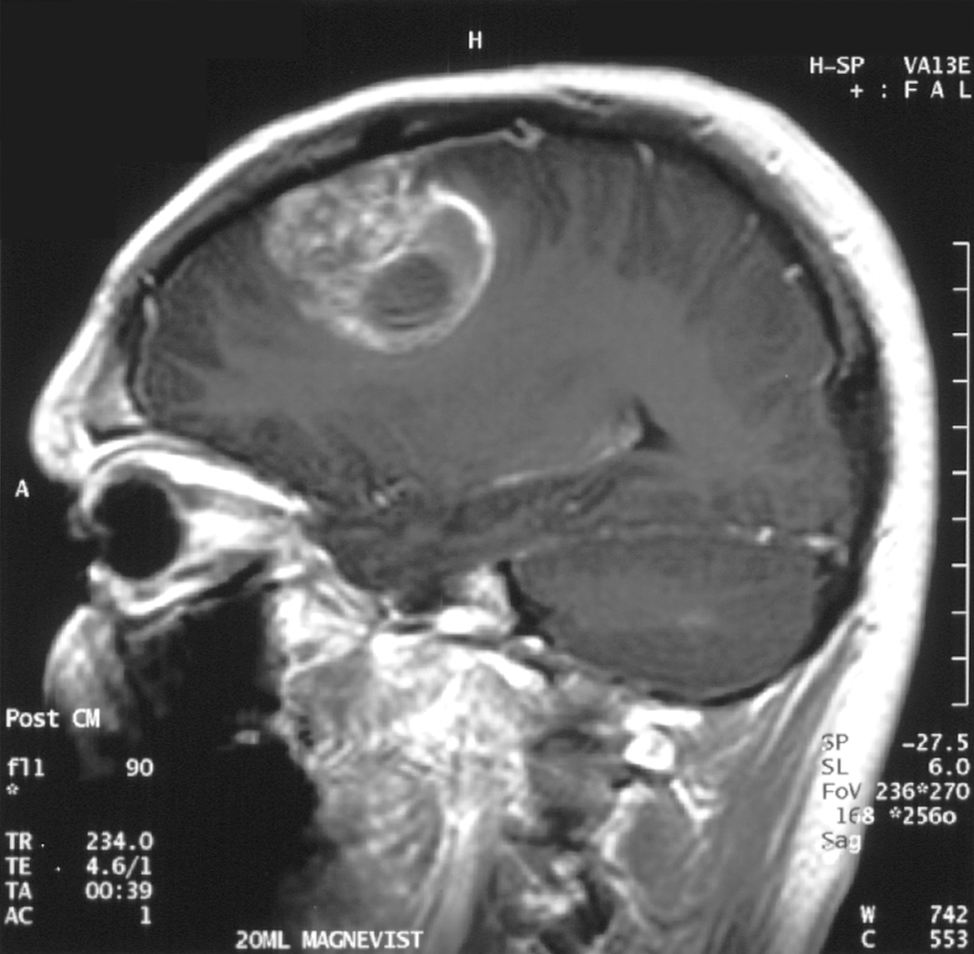

An interdisciplinary team of researchers from the University of Notre Dame is investigating the mechanisms of neuron death caused by chronic compression – such as the pressure exerted by a brain tumour – to better understand how to prevent neuron loss.

Published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, their study found that chronic compression triggers neuron death by a variety of mechanisms, both directly and indirectly. The research is helping lay the groundwork for identifying therapies to prevent indirect neuron death.

“The impetus for this project was to figure out those underlying mechanisms. In cancer research, most researchers are focused on the tumour itself, but in the meantime, while the tumour is sitting there and growing, it’s damaging the organ that it’s living in,” said Meenal Datta, the Jane Scoelch DeFlorio Collegiate Professor of Aerospace and Mechanical Engineering at Notre Dame and co-lead author of the study. “We fully believe that these growth-induced mechanical forces of the tumor as it expands is part of the reason we see damage in the brain.”

As an engineer who leads the TIME Lab, Datta studies the mechanics of tumors and the microenvironment, specifically for glioblastoma, an incurable brain cancer. She had found in prior work that tumors damage the surrounding brain. But to understand the mechanisms by which tumors kill neurons from compression alone, Datta needed a “hardcore neuroscientist.”

That neuroscientist is Christopher Patzke, the John M. and Mary Jo Boler Assistant Professor in the Department of Biological Sciences at Notre Dame and co-lead author of the study. Patzke utilises induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs), which are either obtained from external sources or generated directly in his lab. These cells function like embryonic stem cells and can be differentiated or changed in the lab into any cell type in the body, including neurons.

For this study, iPSCs were used to create neural cells and develop a model system of neurons and glial cells that behave as a neuronal network would in the brain. Researchers grew the cells and then applied pressure to the system to mimic the chronic compression of a glioblastoma tumour.

After compressing the cells, graduate students Maksym Zarodniuk and Anna Wenninger, from Datta and Patzke’s labs respectively, compared how many neurons and glial cells died versus lived.

“For the neurons that are still alive, many of them have this programmed self-destruction signaling activated,” Patzke said. “We wanted to understand which molecular pathway was responsible for this; is there a way to save neurons from going down the drain to this cell death mechanism?”

By sequencing and analysing all messenger RNA from the living neuronal and glial cells, the researchers found an increase in HIF-1 molecules, signalling for stress adaptive genes to improve cell survival, which leads to inflammation in the brain. The compression also triggered AP-1 gene expression, a type of neuroinflammatory response.

Both neurological reactions are indicators that neuronal damage and death is underway.

An analysis of data from the Ivy Glioblastoma Atlas Project shows that glioblastoma patients also reflect these compressive stress patterns and gene expression changes as well as synaptic dysfunction in line with the experiment’s results. The researchers confirmed these results by mimicking force via a live compression system applied to preclinical models of brains.

Overall, the findings may help explain why glioblastoma patients experience cognitive impairments, motor deficits and elevated seizure risk. Additionally, the signalling pathways offer opportunities for researchers to explore as drug targets to reduce neuronal death.

“Our approach to this study was disease agnostic, so our research could potentially extend to other brain pathologies that affect mechanical forces in the brain such as traumatic brain injury,” Datta said. “I’m all in on mechanics. Whatever it is that you’re interested in when it comes to cancer, above your question of interest, mechanics is sitting there and many don’t even know they should be considering it.”

The mechanics of compression and its effect on neuron loss is key for future research.

“Understanding why neurons are so vulnerable and die upon compression is critical to prevent excessive sensory loss, motor impairment and cognitive decline,” Patzke said. “This is how we will help patients.”

Source: University of Notre Dame